How African governments go about the challenges of dealing with the pandemic will shape the future of the continent for many years. In this Africa in Fact series of blogs, six of our correspondents across the continent will report over the next twelve weeks on aspects of their governments’ policies and actions.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the corona virus a pandemic on 11 March, and most governments, including many African governments, have adopted a range of measures to contain it. Most countries have opted for a lockdown, with citizens required to stay at home and observe social distancing when not at home. The Asian Development Bank estimated that the drop in economic activity will cost between $5.8 tn and $8.8 tn, equal to between 6.4% and 9.7% of global economic output (BBC, 15 May 2020).

The Asian Development Bank estimated that the drop in economic activity will cost between $5.8 tn and $8.8 tn, equal to between 6.4% and 9.7% of global economic output (BBC, 15 May 2020).

In their lack of preparedness, governments and elites around the world show that they have failed to learn the lesson of the crisis of 2008, commented Nobel-prizewinning economist Joseph Stiglitz on 15 April in Foreign Policy: they had been happy to create a new international financial system that was “good at absorbing small shocks, but was systemically fragile”. They had not, he suggested, planned for systems that were resilient to large shocks.

Other prominent global thinkers also briefly outlined their views on the core issues relating to the pandemic. Most were concerned that businesses and governments would resort to economic nationalism, and that the crisis will usher in growing inequality both within and between nations with many attendant issues, such as food security and energy security. Global trends toward digitalisation and work automation will also likely speed up – further widening the technological gap between the developed and developing countries. Many businesses (mostly small companies) and jobs will be lost.

While the pandemic is the first crisis to “engulf” both developed and developing economies, according to Harvard’s Carmel M Reinhart, it will likely have very different effects on them. The poor living conditions of most of Africa’s inhabitants will make it difficult to contain and mitigate the pandemic, while some governments’ “neglect of marginalised segments of society” has left many people vulnerable to the disruption of such a large-scale shock, according to Eddie Ndopu, a UN Secretary-General’s Advocate for the Sustainable Development Goals (weforumorg, 1 April 2020).

In mid-April, the ILO said the pandemic would destroy 195 million jobs globally and “drastically cut the income of another 1.25 billion, most of whom are already poor”. The pandemic is a “magnifying glass” on inequality both in and between countries, according to columnist Andreas Kluth (Bloomberg, 13 April 2020). In the US, the wealthy can self-isolate while workers must continue working, thus facing a greater risk of infection. The virus moves faster through poor neighbourhoods, and disproportionally kills black people.

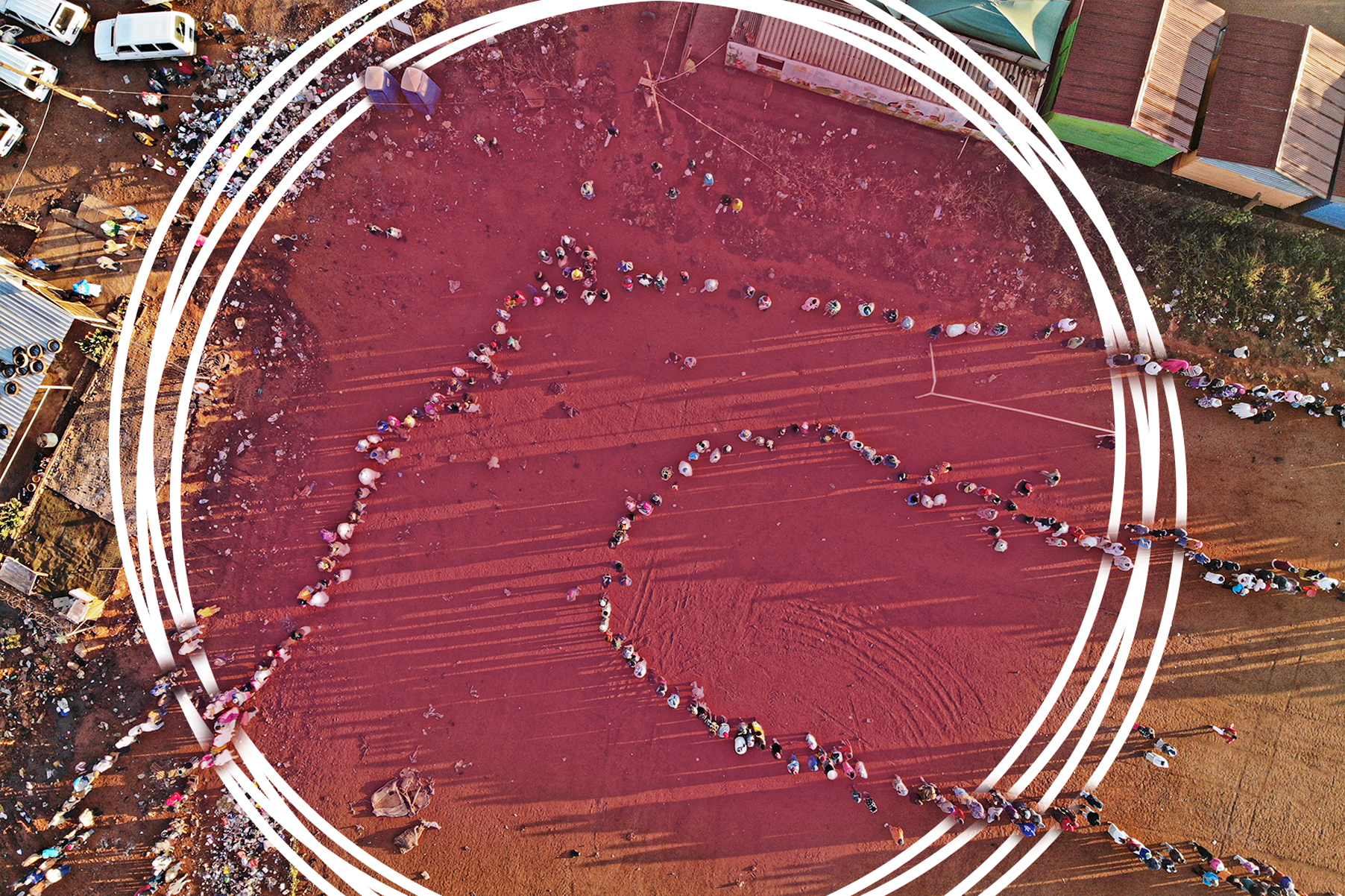

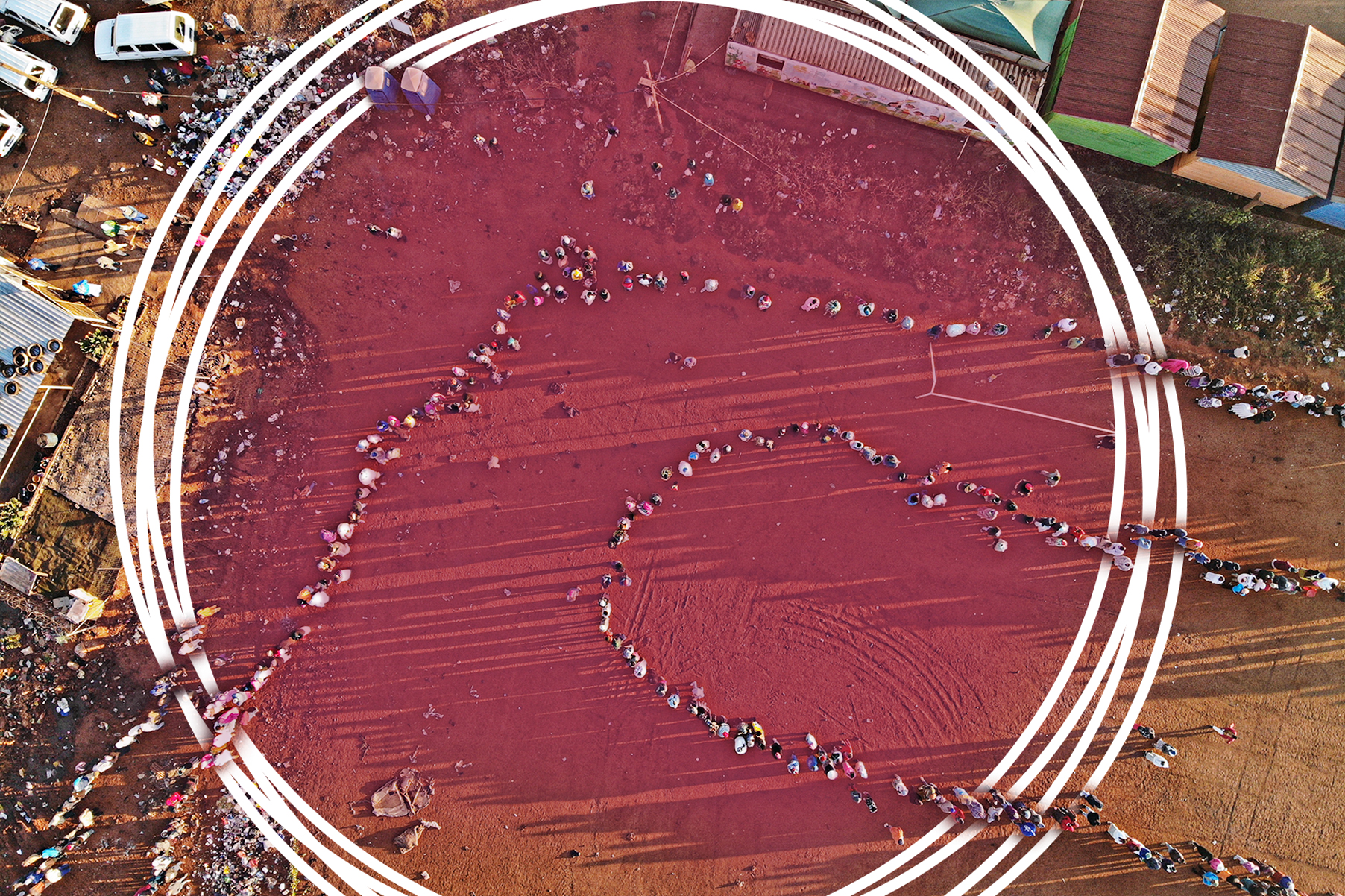

Yet these social differences are even more extreme in a “shantytown in India or South Africa”, Kluth points out. For many people in developing countries, social distancing is impossible. Moreover, as Richard Cash and Vikram Patel argue in 2 May 2020 article in The Lancet, lockdown conditions are also not practicable, and hunger is an immediate threat to the two billion people who work in informal economies around the globe. As a result, inappropriate policies aimed at addressing the pandemic might result in more social uprisings, especially in developing countries.

Estimates of the immediate, public health effects of the coronavirus on Africa vary widely. A mid-April report by the UN Economic Commission for Africa predicated some 1,2 billion infections and 3.3. million deaths in Africa from the virus over the next year. However, the WHO estimates that about a quarter of a billion Africans will be infected, and that the continent will suffer about 190,000 deaths from the virus. It must be said that the reports are not strictly comparable, as they are based on different sets of data.

The WHO estimates that about a quarter of a billion Africans will be infected, and that the continent will suffer about 190,000 deaths from the virus.

The WHO study argues, for instance, that Africa’s youthful population will contribute to lower transmission rates. It is believed that the Covid-19 virus is more infectious and fatal for older people, for men, and for the obese. If so, lifestyle factors, such as the continent’s relatively low proportion of obese people, may help, as Karen McVeigh suggests, writing in The Guardian on 15 May 2020. But in reality, both studies are based on limited assumptions. “Prediction”, as the scientists insist, is a matter of probabilities.

“[A] disproportionate share of the world’s poor risk massive upheaval as health, political, and economic systems struggle to manage the pandemic,” according to Kaysie Brown and Megan Roberts, two senior officers of the UN Foundation (‘Tackling COVID-19’, Council on Foreign Relations, 24 March 2020). Of all the continents, Africa is likely to be most seriously affected on every level.

No fewer than 33 African countries are among the least developed in the world. According to a 2016 RAND Corporation report, 22 out of the 25 countries most vulnerable to infection outbreaks are in Africa (Kaan Devecioglu 2 April 2020, Andolu Agency). “The welfare of a billion people depends on how governments balance saving lives from the virus while minimising economic damage in a continent where more than 400m people live on the equivalent of less than $1.90 a day,” according to The Economist on 26 March 2020.

In this series of blogs, six Africa in Fact correspondents across the continent will use the “wicked problem” lens to report on their governments’ policies and actions. In outline, a “wicked problem” has “multiple stakeholders involved in complex and unpredictable interactions”, according to Williams and Van ‘t Hof (2014). More specifically, “wicked problems” may have no definitive description, nor any one “correct” solution, and it can even be difficult to know when and if they have been solved. Our blog series will look at the following six broad themes, each of which represents part of the C-19 “wicked problem”:

- Leadership Style;

- Rule of Law;

- Work and Jobs;

- Public Health Measures;

- Social Support Measures; and

- Planning The Future We Want.

Each of these areas represents a choice out of many options. But each theme selects an area of life, at least, that is clearly crucial to Africa’s future. How, in fact, have African governments been dealing with this unprecedented crisis in these areas?

Certainly the Covid-19 pandemic represents “something new under the sun”, according to Columbia University’s Adam Tooze. No crisis in the modern world has been so extensive, multi-facetted, or fraught with large but unpredictable consequences. Governments around the world, and African governments in particular, face immense pressures and challenges.

No crisis in the modern world has been so extensive, multi-facetted, or fraught with large but unpredictable consequences.

Yet as noted, in policy studies, such situations can be described as “wicked problems” and they can be addressed. They involve multiple stakeholders in complex and unpredictable interactions. That is, every complex problem has constituent parts in various relationships with each other. Together, they make up the overall shape, or structure, of the problem. A systemic analysis of a “wicked problem” will start, then, by looking closely at the stakeholders involved, as well as their relationships and their perspectives. The approach is outlined in the following steps:

Relationships

- Who and what are the elements of the problem situation?

- How do their processes contribute to the situation?

- What sort of relationships exist between them? (friendly, antagonistic e.g.)

- What patterns emerge from these relationships?

- Which relationships are key to the situation?

Perspectives

- Which stakeholder roles are key to solving the situation?

- What are the key stakes involved?

- What are the stakeholders’ perspectives on the situation?

- How do their perspectives shape their actions and expectations?

Evaluation

- Which key relationships are privileged and marginalised?

- Which key perspectives are privileged and marginalised?

- What ethical, political and pragmatic considerations are important?[1]

This approach does not, and cannot aim at a particular “solution” that is specified beforehand. The angle we take on the problem will influence our decisions in each of these areas.

In the context of Africa’s response to the C-19 crisis, stakeholders might be governments, scientists, citizens, and medical supplies companies, for example. Or they might be governments, workers, businesses and legal advisers. Similarly, the relationships between stakeholders will be shaped by the angle we take. Pharmaceutical companies might have a cooperative or an antagonistic relationship with government, depending on context.

And finally, even how we evaluate the overall situation – that is, what we regard as a “solution” – will also be partly determined by the angle we take. Is the main purpose to protect public health? Or is it to protect the economy? Or to ensure that the country is closed to outside influence? And how might policymakers be influenced to protect health and economic dynamism simultaneously?

“Wicked problems” may appear intractable, but they have been effectively studied and addressed just because they are an increasingly influential factor in modern societies. Very different answers to these questions are playing out in different governments’ responses to the crisis today. And as with other “wicked problems”, we believe that a clearly outlined systemic approach to the major themes of Africa’s C-19 crisis can provide a helpful backdrop to evaluating and strengthening the response of African governments to the pandemic.

We are pleased to have a stellar group of writers working with us on this series. They are:

Vanessa Offiong – Abuja, Nigeria

Amindeh Atabong – Yaounde, Cameroon

Tamrat Georgis – Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Mark Kapchanga – Nairobi, Kenya

Sarah Nyengerai – Harare, Zimbabwe

Owen Gagare – Harare, Zimbabwe

Paula Fray – Johannesburg, South Africa

To find out more about each of them, check out their biographies elsewhere in this Africa in Fact microsite. Each of the countries they work from is having a very different experience of this C-19 crisis. We look forward to hearing from them over the next twelve weeks as they build up a truly pan-African picture of the pandemic and what our governments are doing, or could better be doing, to mitigate it.

We’d love to hear from you! Join The Wicked Conversation by leaving your comments below, or send your letter to the editor to richard@gga.org.

[1] Adapted from Williams and Van ‘t Hof, Wicked Solutions, 2014, pp 18-22.

Richard Jurgens is a former editor of GGA’s flagship publication, Africa in Fact, and has been appointed as editor of GGA’s peer-reviewed academic journal, The Africa Governance Papers. He spent 10 years in exile with the ANC in Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, as well as the Netherlands. He has worked in mainstream media, alternative media, the corporate world and for NGOs internationally and in South Africa. A published author with a memoir, a novel and several books of poetry to his name, he has a BA (Hons) in philosophy and is currently completing a Research Master’s degree in public policy studies at the University of the Witwatersrand’s School of Governance.