Endgame: health after lockdown

African countries must realise that resilient public healthcare systems are a human security issue and vital for stable government

A police officer beats a female orange vendor on a street in Kampala, Uganda, on March 26, 2020, after Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni directed the public to stay home for 32 days starting March 22, 2020 to curb the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. – Ugandan authorities have identified 14 confirmed cases of the COVID-19 coronavirus in the country. All borders have been closed except for limited goods and authorised emergency flights. (Photo by Badru KATUMBA / AFP)

On 11 March, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced its decision to classify COVID-19 as a global pandemic. At the time, the number of cases of COVID-19 outside China, where the disease is known to have originated in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei province, had “increased 13-fold, and the number of affected countries has tripled”. On the same date, the global health watchdog announced that there were more than 118,000 cases recorded in 114 countries, while 4,291 people had lost their lives. A month earlier, on 11 February, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention announced that several African countries were dealing with suspected cases under investigation, including in Angola, Botswana, Ethiopia and South Africa among others. There were no confirmed cases reported on the rest of the continent.

South Africa was to report its first confirmed case on 5 March, one of a group of people who returned to the country after participating in group travel to Italy. With a number of cases that were later confirmed in different parts of the continent by the end of March, and before South Africa emerged as an epicentre of the pandemic, several countries, including Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe, among others, started implementing hard lockdown measures to curb the spread of the virus. On 23 March, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that the country would be put into a nationwide lockdown for 21 days with effect from midnight on Thursday, 26 March. While South Africa had one of the strictest lockdown measures on the continent, if not globally, with a ban on the sale of alcohol, cigarettes and strict curfews, these precautions had something in common with other African countries.

They were all accompanied by strict securitisation measures, with an almost suspension of universally accepted freedoms such as movement and association. Soldiers and police were deployed to the streets on different parts of the continent to enforce lockdown measures. So, the big question is, why did African countries choose this hard security route to control the spread of COVID-19? It appears that these measures were inspired by China’s lockdown strategy, which according to The Guardian newspaper was “brutal but effective”, characterised by a “total shutdown of activity in Hubei province, including all shops except those selling food or medicine”. According to political scientist and international relations expert Zuhal Yeşilyurt Gündüz writing in 2006 in the context of the global health threat posed by the HIV/AIDs epidemic, “securitisation implies the construction of a danger that needs to be changed by quick action and extraordinary, even undemocratic measures”.

Gündüz further explains: “By securitising an issue, public authorities show it as an existential threat, requiring extraordinary measures and justifying actions outside the normal bounds of political procedure. Putting something on the security agenda persuades us of the need to furnish urgent and unprecedented responses, it signals imminent danger and is therefore given a high priority. ” The securitisation response of African governments to COVID-19 is rooted in the disease as an existential threat, which would have claimed millions of people on the African continent if it was not properly managed. According to Amnesty International, poor health infrastructure in countries – even in larger economies such as South Africa and Nigeria – means that the poor and marginalised are at greater risk of dying from COVID-19 related complications due to lack of access to appropriate healthcare and treatment. In most parts of the continent, healthcare infrastructure has not expanded to cater for Africa’s growing population, although private healthcare has thrived, catering to those with the economic means to afford it due to the appalling state of our public healthcare.

Ugandan police officers and members of Local Defence Units (LDU), a paramilitary force composed of civilians, patrol during the curfew after 7pm in Kampala, Uganda, on April, 29, 2020. – Ugandan President on April 14, 2020, ordered the extension of a 21-day nationwide lockdown with a strict night curfew, in a bid to halt the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. (Photo by SUMY SADURNI / AFP)

There has been typhoid and cholera, both of which are waterborne diseases, in Zimbabwe in recent years and these have claimed the lives of thousands of people, including in urban Harare. COVID-19 would have been the final nail in the coffin for a country like Zimbabwe with collapsed public health infrastructure if the pandemic had been more aggressive on the continent. Claims have been made that the Zimbabwean government introduced strict COVID-19 preventative measures partly as an excuse to crack down on dissent. According to Amnesty International, there has been a renewed assault on human rights, including the right to freedom of expression in recent months, especially targeting journalists, activists and human rights defenders who have spoken out against alleged corruption and called for peaceful protests. While self-isolation and social distancing were touted globally as some of the best precautions to avoid spreading COVID-19, these measures have not proved practical in Africa’s townships and informal settlements, which are poor and overpopulated.

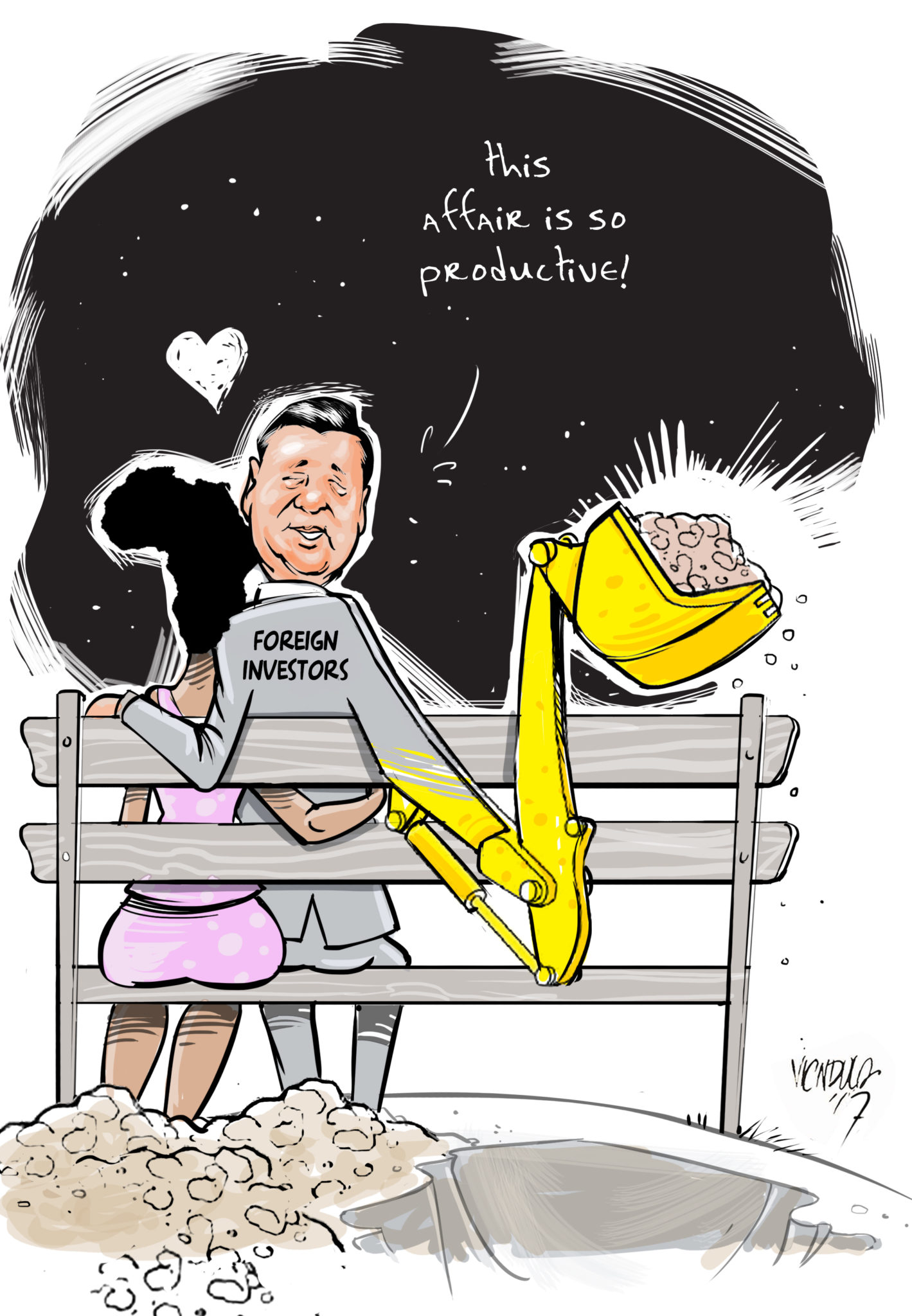

Many of these also have no access to essential services such as access to clean running water, vital for maintaining hygiene, owing to poor service delivery, corruption and aged water infrastructure. There is no arguing that a healthy nation is a productive one. Countries that have a healthy workforce are some of the most productive economies in the world. After the first world war, on 21 December 1918, The Economist called for “more state involvement to improve public health in Britain”, arguing that “until we all know how to be healthy and strong, and recognise that unless we are so we cannot pull our weight in the boat, … a low standard of health and efficiency will continue to be a drag on the nation’s productive power.” This is equally true for Africa, where improving public healthcare infrastructure would come with economic benefits for the continent. In their paper ‘Why African Countries Need to Participate in Global Health Security Discourse’, published in the journal Global Health Governance in 2011, Hwenda et al argue that “global health security considerations have been increasingly shaping multilateral decisions in the global governance of health”.

They rightly point out that the “African group and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) undermine their interest by disengaging from the ongoing global health security discourse, which is increasingly informing multilateral discussion in the World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations (UN) Security Council and elsewhere”. They recommend that African countries “need to consider the potential benefits of participating in shaping the global health security agenda in order to advance their health security interests”. For years, African countries have heavily funded defence and the military at the expense of healthcare, itself a national security issue, with no apparent territorial external threats to their countries. For example, a 2020 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) report said that “African military spending grew by 17%, rising to $41.2 billion in 2019, over the past 10 years”. The Institute reported that in 2019, the world recorded the largest annual growth in military spending since 2010, rising 3.6% from 2018 to $1.917 trillion.

It is against this background that it is worth noting a 2019 Brookings Future Development report that said – in per capita terms – the rest of the world spends 10 times more on healthcare than Africa. The same report noted that 98% of Tanzania’s funding for HIV/AIDS came from external sources. As the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals have rightly pointed out, good health is essential to sustainable development. Yet, according to the United Nations Development Programme, at least 400 million people in Africa have no basic healthcare and 40% percent lack social protection. It is important, therefore, for Africa to invest in healthcare infrastructure to prepare the continent to cope with its rapidly growing population and future pandemics like COVID-19, and other future transnational diseases.

In some African countries, political leaders would want to have us believe that political activists who demand their right to freedom of expression and assembly are a threat to national security. But the truth is, failure to invest in public services such as healthcare presents the biggest threat to national security. It will take commitment and visionary leadership to build world-class public healthcare in Africa, which will need prioritising to achieve that goal, but as a continent we can build a resilient public healthcare infrastructure if we put our mind to it.

Robert Shivambu has experience mainstream media and human rights environments. His career spans more than a decade in both fields. He is currently a media manager at Amnesty International’s International Secretariat (IS) responsible for the Southern African regional office based in Johannesburg. He previously worked for both PowerFM98.7, a Johannesburg-based talk radio station, and eNCA as Africa correspondent. He has a sophisticated understanding of media and International Relations and he is qualified in both fields with the Tshwane University of Technology in Pretoria and the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg