July 2022 marked the height of Eskom’s key dysfunctions, and once again brought South Africa’s state-owned electricity utility to the centre of national governance debates. For the second time since 2019, South Africans experienced Stage 6 “load shedding”. “Load shedding” is a euphemism for rolling blackouts to alleviate pressure on the national transmission grid, given that demand currently outstrips generation capacity, which is operating at between 60% and 65% of full capacity. Each stage represents increasing increments of power unavailability. During stage 6, around 6000 MW are shed, for up to six hours a day, to decrease the load on the national grid.

Power lines leaving the Eskom’s Duvha Power Station in the coal rich Witbank region of South Africa. PHOTO: MARCO LONGARI/AFP

According to the latest report by the The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), South Africa has experienced at least seven distinct periods of load shedding in the last 15 years, with trends becoming progressively worse since 2018. Between 2020 and 2021, the number of hours spent load shedding increased by over 300 hours or 12.5 days, for an approximate total of 1,169 hours, or 48 days. The amount of energy shed in 2021 alone constituted a near-40% increase in total energy shed when compared to 2020, highlighting the increasing severity of Eskom’s capacity constraints. Against a full 2021 year, July 2022 outages overtook previous years and experienced a total of 1270 hours, or 53 days, of national outages. Therefore, in 2022, South Africa experienced nearly as many outage hours as 2019 and 2020 combined.

Public reaction has been strong. Eskom’s CEO, Andre de Ruyter, has also made pleas for the private sector to be permitted to increase its power generation to feed the grid. President Cyril Ramaphosa has answered de Ruyter’s call by announcing that red tape for private sector generation will be reduced, and that the fifth and sixth bidding rounds for the REIPP programme will be sped up (and the MW required increased). Additionally, Minister of Mineral Resource and Energy (DMRE), Gwede Mantashe, has called for a second Eskom under the auspices of the DMRE. Before this kind of initiative can be considered, however, it is necessary to understand the history of South Africa’s energy sector, to avoid making more mistakes.

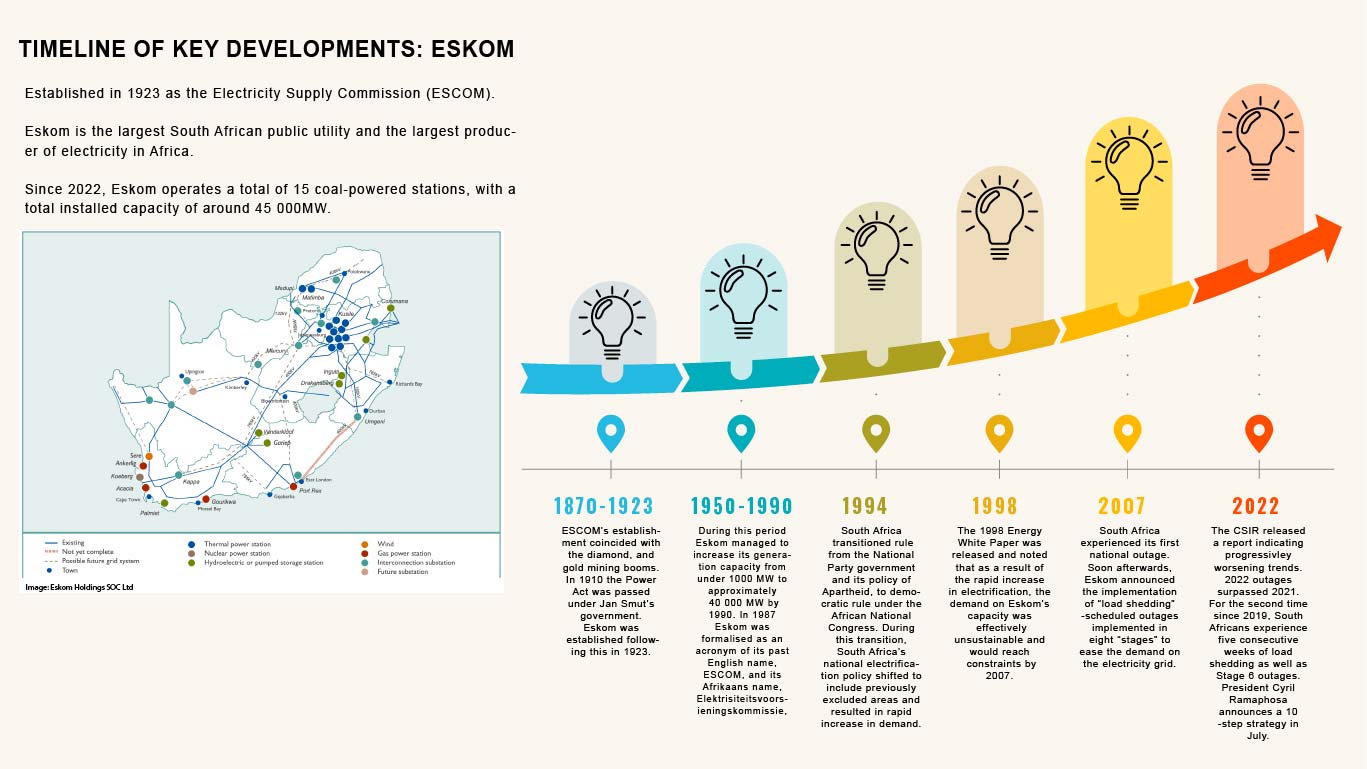

Before its founding as the Electricity Supply Commission, or ESCOM, the electricity market in South Africa during the late 19th and early 20th centuries was distributed by municipalities and private companies. The development of South Africa’s electricity industry coincided with the diamond and gold mining booms, which attracted a high volume of economic activity to the Kimberley, Witwatersrand, and Free State regions during this period. Coal mining in what is now Mpumalanga was subsequently established as a key resource that could supply energy and stimulate economic activity in the adjacent colonial settlements that had developed.

Coupled with the increasing global demand for South African diamonds, gold, and coal, the generation of electricity powered urbanisation, and early industrial development. The Transvaal Colony under British rule sought to capitalise on this. It passed the Power Act of 1910. This act defined electricity as a public service, with the electricity generation utility to be owned and operated by the government. A few years later, General Jan Smuts’ government passed the Electricity Act of 1922, which outlined the basis for the development of a state-run electricity supply industry in South Africa that would provide “wherever required, a cheap and abundant supply of electricity”. However, under the Electricity Act, naturally integrated networks were racially segregated, and local authorities were granted sole control over electricity distribution within their areas of jurisdiction. This meant that local authorities often purposefully failed to supply the local black population with electricity, and in doing so, underestimated the total population and therefore demand.

Between 1950 and 1960, the total installed capacity grew from 1500 MW to 4000 MW. By 1970, it was at around 13 000 MW, growing to 23 000 MW by 1980. By 1990 the total installed capacity was 40 000 MW and Eskom was supplying some of the world’s lowest-cost electricity, dominated almost entirely by coal. Ultimately, the colonial and apartheid government’s intentions to produce and supply cheap electricity to stimulate economic growth were successful.

However, this success was partly a result of deals that benefited oligopoly businesses and elites, at the expense of failing to meet the service delivery requirements of the majority of the population. This meant that formerly Black areas of administration (which constituted almost 75% of the population) were neglected and left without electricity through much of the 19th century. It was not until democratisation in the late 20th century that the national electrification policy prioritised equal access to electricity.

In 1994, under the African National Congress (ANC), South Africa’s energy sector experienced a surge in demand as the newly elected democratic government shifted focus and undertook to achieve the electrification of previously neglected residential homes, and provide low-cost electricity for economic growth. According to the World Bank, in 1996, access to electricity in rural areas was around 23.8 % compared to 85.3% in urban areas. By 1997, access to electricity in rural areas had risen to 40.4% in rural areas, and 85.4% in urban areas.

By 2007, South Africa’s population had grown, and access to electricity had expanded to 82% of that population, according to the World Bank. However, this was accompanied by relatively low development of its electrical generation capacity and transmission infrastructure. This led to a national grid overload and South Africa’s first national outage. Following this outage, Eskom warned that, over the next five or six years, the system would be constrained. In 2008, in response to the now intensifying energy crisis, the government decided against utilising the private sector’s balance sheet once more and instructed Eskom to commission two new coal-fired power plants, the Medupi and Kusile plants. However, due to construction delays, cost escalations, and design defects, the newly constructed power plants were inefficient solutions to Eskom’s generation woes. They are still not operating at full capacity, with the first phase of Kusile having only just come on stream. Bloomberg has estimated the final price tags on the two projects at R464 billion.

In response to the national 2007 grid outage, the government introduced “load shedding” as a means of coping with the high-demand low-supply dilemma, ie., cutting power supply to certain areas of the grid. They posited a “load shedding schedule” that outlined at first 4, 6, and then 8 “stages” of load shedding, each with a correlating amount of electricity supply it would remove from the grid. In April 2008, South Africans first experienced scheduled outages which totalled approximately 100 hours or four days, shedding approximately 176 GWh of energy. According to the National Energy Regulator of South Africa, the 2008 outages cost the South African economy R50 billion.

So where is the government now? President Ramaphosa recently announced an energy crisis action plan that aims to increase energy security and end load shedding. Among these initiatives include the removal of licencing thresholds for private energy providers that feed into the electricity grid, buying electricity from existing independent power producers, and importing power from Botswana and Zambia. Additionally, installing solar panels in businesses and residential homes has been encouraged and Eskom intends to incentivise those that look to install solar panels.

In the next analysis piece, we closely examine the above key reforms and implications associated with them, particularly Eskom’s debt burden, and alternative energy sources given South Africa’s declining energy availability factor and the role of the National Energy Crisis Committee established by President Ramaphosa. If Eskom is to have any hope of recovering, or meeting its mandate of electricity for all, the South African government would seriously benefit from considering its past oversights critically, lest it falls prey to them again.