Government-instituted regulations restricting physical contact and movement to combat the Covid-19 pandemic dramatically spurred the use of digital diplomacy in Africa, using Information and Communication Technologies (ICTS). This gave digital technologies a prominent role in the conduct, management, and administration of foreign relations.

While there is a growing focus on African conceptual-cum-empirical studies and commentary on digital diplomacy, this article draws attention to the challenges of digital diplomacy in Africa, US, and China relations. Despite its potential, the practice of digital diplomacy in Africa faces serious challenges.

The shift towards digital diplomacy has provided huge opportunities for low-cost, equal diplomatic tripartite relations between the US, China, and Africa, often skewed in favour of the two major powers. However, serious ideological, political, geopolitical, and infrastructural resource challenges impinge on the democratisation and transformative impact of digital diplomacy.

Participants in the presidential summit of the Mandela Washington Fellowship for Young African Leaders use a variety of mobile devices, including tablets and phones, in Washington, DC. Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images via AFP

Where financially constrained African governments once invested massive resources travelling abroad to engage in face-to-face meetings, ICTS-driven diplomatic engagement, management, and policy analysis – conducted through Zoom, Google meets, Skype, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube, using voice- and video-streaming services connected to the internet – have become the norm.

From multilateral conferences organised by the African Union (AU), Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and national government meetings, African diplomats and heads of state are using digital tools in their daily work, conferences, negotiations, representation, communication and policy analysis. Gone are the days when African governments ran without computers and internet connectivity.

The revolutionary domestic socioeconomic impact of ICTs is evident in various sectors, for example, access to and the use of cellphones, and their transformative impact on remittances, cash transfers and payments. The use of ICTs lies in promoting free speech, human rights, and the free flow of information while inspiring entrepreneurial socioeconomic innovation and citizen empowerment.

Pupils from Light House Grace academy in Kawangware, Nairobi, use the Kio tablet created by a local technology company, BRCK Education, during a class sesssion in October 2015. Photo: Simon MAINA / AFP

Despite these gains, Africa lags behind China and the US in terms of laying down structures, institutions, and policies governing the use and management of digital diplomacy. Given the fortuitous leveraging of digital diplomacy under stringent Covid-19 regulations, many African diplomats instinctively embraced ICTs. But the transition to digital diplomacy proceeded ambiguously, in a policy vacuum, lacking strategic state-driven planning. Until 2019, African governments did not prioritise the internet and digital diplomacy within their foreign policy strategies and policies.

In contrast, both China and the US are well advanced in terms of institutionalised public and digital diplomacy, with dedicated research institutions, structures, and policies.

The US is one of the first countries to realise the importance of the internet for promoting national interests abroad, as the US State Department became one of the world’s leading users of digital diplomacy in the pursuit, coordination, and communication of American priorities to internal and external actors. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) has adopted a digital strategy to promote the responsible use of digital technology in development and humanitarian work by local innovators, the private sector, and civil society. US officials are also pushing for an IT and digital policy guided by a grand, overall strategy to maintain global tech leadership, limiting China’s global dominance in the IT and digital space.

China’s digital diplomacy takes a highly centralised approach, using state agencies, diplomatic missions, Confucius Institutes (CI), state and non-state funded companies, and media. A network of diplomats around the world has become the main means of getting its messages out through social media. Chinese diplomatic voices make themselves heard online through the offices of the consul generals and a new generation of digitally savvy diplomats.

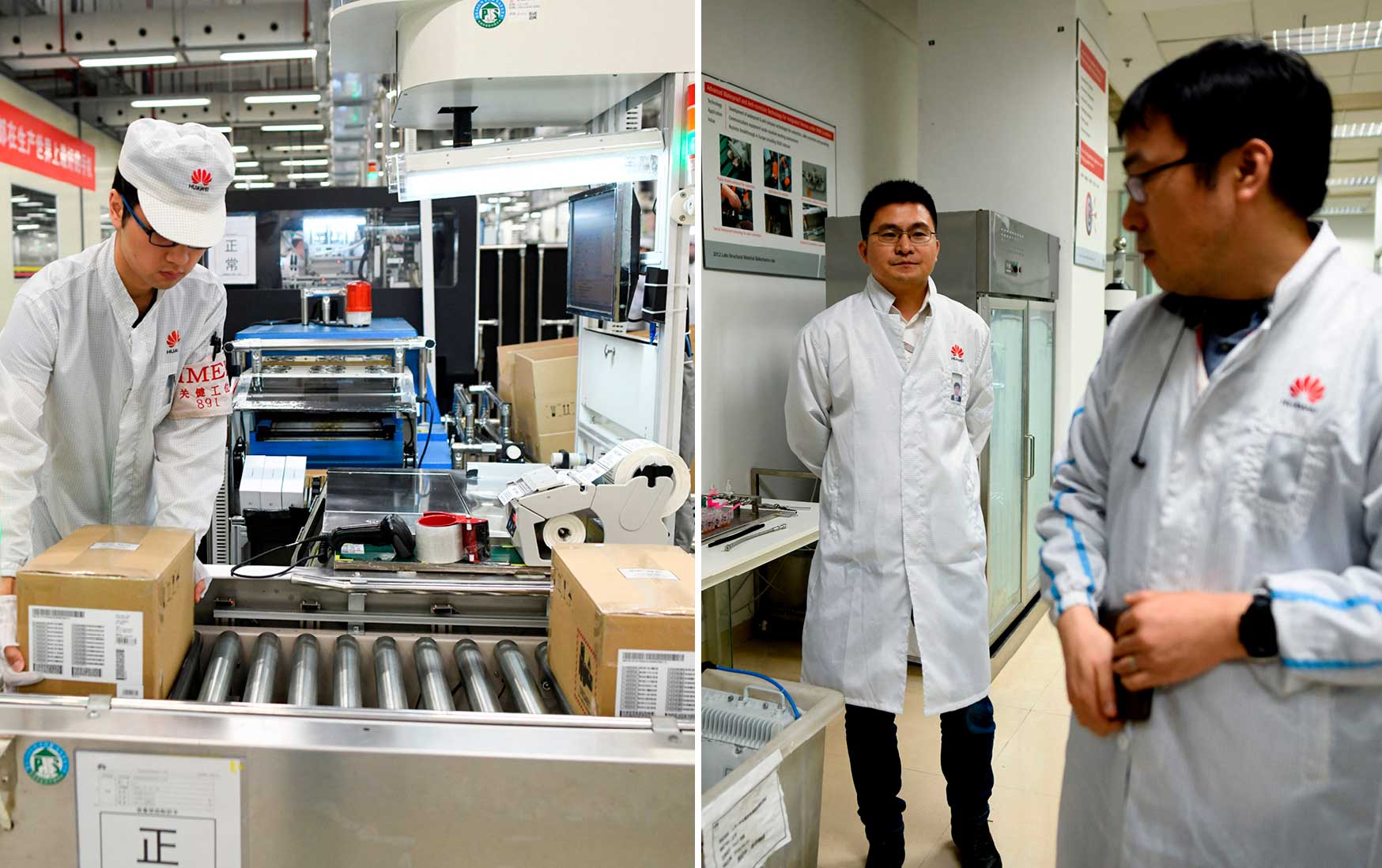

The Chinese telecom giant, Huawei, gave foreign media a peek into its state-of-the-art facilities as the normally secretive company stepped up a counter-offensive against US warnings that it could be used by Beijing for espionage and sabotage. Photos: WANG ZHAO / AFP

Africa generally faces huge shortages of infrastructure, and secure, faster internet connectivity minimising the efficacy of digital diplomacy. The comparatively low private and public investment in assets such as fibre and broadband facilities, computers, and cellphones imported at higher cost from China and the US diminishes the reliable use of digital diplomacy.

The public sector has struggled to inject bigger investment into ICTs, to sponsor policies and regulatory frameworks, which stimulate growth and provide effective use of digital diplomacy. The Infrastructure Consortium for Africa (ICA) suggests that as of 2015, about 75% of the population and 15% of households in Africa had no access to the internet. Despite the significant growth in ICTs, mobile telephony use in the continent stands at 60%. Although investment in ICTs continues to grow, it is unevenly spread and poor rural African populations, living in areas that offer poor incentives for ICTs investment, are marginalised from digital society.

But the main challenge to positive digital diplomacy between Africa, China, and the US is the polarised political rivalry between the US and China. Geopolitical rivalry, characterised by exclusionary competition over natural resources, has diminished collective mutual benefits with Africa. Digital diplomacy has, therefore, been reduced to a mere means to an end, as Africa is subjected to often-opposed geopolitical interests.

The continent lies at the intersection of a digital dependence either on the US or China, making African countries highly vulnerable to the disruption of data flows, cyber attacks undermining the protection of strategic public and private information resources from illegal eavesdropping, and digital sovereignty.

Huawei employees working on the mobile phone production line at a Huawei facility during a media tour in Dongguan, China’s Guangdong province in March 2019. Photos: WANG ZHAO / AFP

The importation of ICTs into Africa as foreign direct investment (FDI), multilateral or bilateral aid has escalated competition between China and the US and their tech companies for control of infrastructure such as internet service providers, search engines, operating systems, undersea cables, satellites, the development of apps, content platforms, mobile handsets, data networks, mobile money, web browsers and content platforms in Africa, and subsequently, digital diplomatic leverage over the continent.

Where China has used state-driven collaboration with its domestic mega tech companies to dominate the African digital markets, the US relies on private-sector driven flagship tech companies to accelerate and scale critical digital infrastructure and capabilities, intensifying geopolitical tech rivalry in Africa. Chinese heavyweight companies such as Huawei Technologies, Zhongxing Telecom Ltd (ZTE), China Telecom, and Alcatel Shanghai Bell (ASB) are at the forefront of providing cheaper ICTs, digital infrastructure, and smartphones driving digital diplomacy in Africa. At the same time, US tech giants such as Facebook, Amazon, and Google are pushing their way into Africa’s digital market.

In 2019, Google launched a subsea cable called Equiano, linking South Africa, Portugal, and Nigeria, asserting the company’s dominance as a search engine of choice in Africa.

China, meanwhile, has donated ICT infrastructure to the AU and member countries, including for strategic public institutions, raising concerns about cyber-security frameworks to protect strategic resources and information. In 2018, the UK newspaper The Guardian reported that Beijing and the AU dismissed allegations that Beijing had bugged the regional bloc’s headquarters.

According to the ICA, Chinese investment in ICTS infrastructure has exceeded $1 billion since 2015. In 2022, German publication Deutsche Welle reported that Huawei –sanctioned in the US, and largely shunned in the Global North due to privacy and security issues – is the largest telecommunications equipment manufacturer in the world, and dominates connectivity in African ICT markets. Huawei components supply 70% of 4G, and is the leading supplier of 5G technologies across Africa, providing cheaper, more affordable, and easy-to-use technologies, with very attractive terms to operators.

Africa lags in domestic access to internet and ICT production, ownership, and deployment of digital technologies as digital diplomacy. While this diminishes continental gains, technological and digital diplomatic capabilities are bolstering the US and China’s geopolitical strategic influence on the continent.

[activecampaign form=1]

Gideon H Chitanga is a PhD student at the University of Pretoria, Political Science, researching regional mediation, pan-African diplomacy and democratic transition. His broader research interests include democracy in Africa, media, diplomacy, international relations and global affairs. Gideon is also a research associate at the African Centre for the Study of the United States (ACSUS), University of the Witwatersrand and an academic fellow at Africa No Filter, a donor collaborative researching how global media cover Africa, focusing on the African narrative. Gideon is Africa analyst for CGTN, and is regularly featured on the major TV and radio channels in South Africa, providing analysis on key continental issues.