A recent article by Craig Singleton in The New York Times – aside from appearing like a job application to work in the new Trump administration – fell only just short of endorsing an America-first attempt to beat China into economic submission through aggressive tariffs: “If Mr Trump can couple the blustery style of his first term with a more focused strategy and tighter discipline, the next four years are a golden opportunity to keep Beijing on the defensive and permanently transform the rivalry in America’s favour.”

Singleton is right, of course, that China is a declining power. Apologies to all the China apologists reading this column. I’ve been following this debate about China as a rising power now for two decades. There is nothing in the data that should convince anyone that China will out-compete the US.

Container ships sit docked at the Port of Oakland, California, on 9 December 2024. US President-elect Donald Trump is threatening new tariffs on multiple countries as his second term approaches, after making tariffs a signature of his 2024 presidential campaign. Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images/AFP.

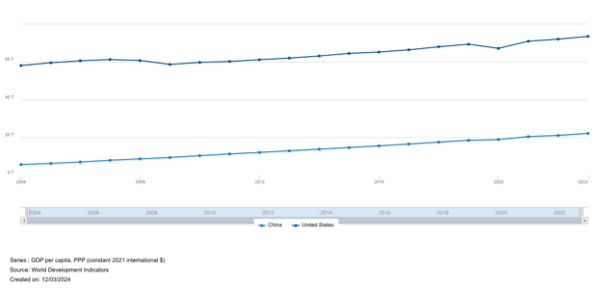

As the graph below makes clear, China is nowhere close to the US in economic performance terms. US GDP per capita, by 2023, was US$73,637 (in constant 2021 $ purchasing power terms). By contrast, China came in at US$22,135. On average, US citizens are 3.33 times wealthier than Chinese citizens. China’s progress over the last 20 years has been impressive on the surface, and the differential has converged. In 2004, US GDP per capita was US$58,153. China’s was US$5,567. You can do the maths. My prediction—at which economists have typically not been that good—is that the differential is unlikely to fall further. China’s growth has been off a very low base. Moreover, the country will grow old before it grows rich thanks to the legacy effects of a disastrous “one-child” policy.

China’s political institutions also render its economic institutions fundamentally incapable of creating the kind of dynamism unleashed in the 1980s under what Yasheng Huang called “directional liberalism”, which ended abruptly with the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. Xi Jinping’s iron grip over power within the Chinese Communist Party since 2012 means that he is surrounded only by yes-men who will not tell him that his economic and foreign policy decisions are wrong-headed.

It is hard to see how the country will recover from building ghost cities that created an enormous property bubble, or how it will now manage its growing debt with an overheated and stagnating economy. Its attempts to move away from an export-led manufacturing growth model into a more services and consumption-orientated economy haven’t worked because the wealth base is neither high enough nor sufficiently broad-based to effect the change.

However, it does not follow that the US should now kick China while it is down. This is an autarkic temptation that defies wisdom. Singleton points out that Trump has “proposed tariffs as high as 60% on Chinese imports”. If you view big-power rivalry as a zero-sum game, this approach might appeal. But the significant risk here is that blanket or arbitrary tariffs on Chinese products would drive US inflation up, which would be an unnecessary global loss.

Inflation, in a nutshell, is the primary factor that brought Trump to power, notwithstanding the out-of-touch urban elitism displayed by the Democrats. While US unemployment is enviously low, inflation hurts cash flow among lowest-paid workers, the very people who voted for Trump. These are the same workers whose jobs are increasingly threatened by mindless digitalisation and automation. As Nobel laureate, Daron Acemoglu, has consistently pointed out, the marginal gains from this approach are insufficient to warrant it.

Higher inflation from arbitrary tariffs on Chinese goods will create acute welfare losses in the US that will be hard to justify politically, especially given the growing automation threat. The Federal Reserve typically responds to inflationary signals by increasing interest rates. We are only just beginning to recover from peak interest rates, and it would be enormously damaging for global growth to return there.

A wiser approach, it seems to me, is to only impose severe tariffs on Chinese products if Xi demonstrates any further aggression (clearly defined and communicated) in the South China Sea and Taiwan invasion ambitions. This can be extended to China’s tacit support for Russia against Ukraine, and evidence of its growing alliance with Iran and North Korea. The US should be careful not to push China deeper into this alliance through random brinkmanship.

Avoiding this would require a careful fine-tuning of tariffs and export taxes for very specific ends. For instance, the US would be wise to diversify its sources of rare earth and other green transition minerals away from China and towards Africa instead, partly through taxing Chinese imports disproportionately. It may also make sense to limit the supply of high-tech goods to China through export taxes, which will prevent it from building more sophisticated weaponry.

This means that the US would do well to provide African countries with genuinely mutually beneficial deals to secure green minerals. China has a significant head start in this arena through its Belt Road Initiative (BRI). The US will have to get smarter in how it engages in Africa, as I argued in this column last month. Preferential access to US markets through a reconfigured AGOA may afford the US an opportunity to place subtle foreign policy conditions on African governments. However, these will only work if those governments see preferential access as a genuine good, concomitant with opportunities to add domestic value—where sensible—to raw materials prior to exports.

Perhaps the more important thing here, though, is that projects like the Lobito Corridor should be configured to avoid reflecting the colonial extraction model. Infrastructure projects should be clearly designed to ensure economic spillover benefits for the entire region through enhancing entrepreneurial dynamism and generating side-stream and upstream opportunities from Africa’s extensive mineral wealth.

In short, Trump and his economic advisers should tread carefully and strategically on the tariff front, not simply to ‘teach China a lesson’ but to ensure gains for its domestic labour force and benefit African countries who would otherwise continue their march into Chinese indebtedness.

- This article first appeared in Modern Mining magazine.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.