Nigeria: many identities

A country of many ethnicities artificially brought together faces many challenges, not least its own development

By Osita Agbu

Historically Nigeria was an artificial creation of the British colonial government. It was designed to be exploited for its natural resources to feed the British industrial sector. Peoples of different nationalities in this large expanse of land—including Hausas, Fulanis, Kanuris, Tivs, Idomas, Igalas, Igbo, Ibibio, Efik, Ijaws, Yorubas, Jukuns and Nupe people—were brought together by the British colonialists to form what was, in effect, a new country. Nigeria’s politics has largely been a contest for power among its three largest ethnic groups, the Hausa/Fulanis, Igbos and Yorubas, found in the north, east and west of the country respectively, while the minorities have been sidelined. After independence this was exacerbated by the fact that Nigeria’s federal system of government is in fact unitary because its constituent elements—the states and local governments—rely on central government for their finances. According to the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) Nigeria had 26 political parties, and an estimated 70 million voters in 2015. The number of political parties poses a major problem for the organisation of elections in the country, especially with respect to logistics, and also with regard to ongoing governance. Where elections have been successful this can be attributed to the refusal of the sitting president not to undermine either the election process or its results. The general elections of 1999, 2003 and 2007 were characterised by serious shortcomings, including a lack of democratic procedures within political parties, manipulation of the electoral process, stolen ballot papers, vote buying, harassment and under-age voting.

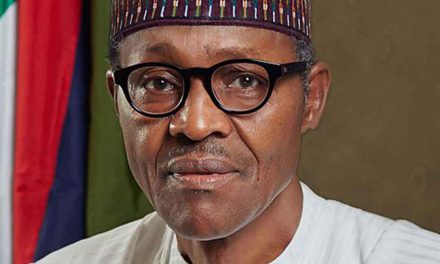

On the other hand, the 2011 and 2015 elections were better organised, partly due to greater political will shown by key stakeholders and the use of technology, namely the Permanent Voters Card and Smart Card Reader, which helped limit electoral fraud. Better supervision of these elections by the INEC under the leadership of Attahiru Jega also contributed to their success. For Nigerians they were important in that they helped establish that both the incumbent in power and the electoral “umpire” can remain neutral before, during and after an election, ethnic considerations notwithstanding. Another conclusion was that transparent leadership and the political will to do the right thing are necessary to mature representative politics. In the view of one retired ambassador, speaking on condition of anonymity, the fact that the peoples of Nigeria are historically and linguistically different means that ethnicity is, and is likely to remain, an important factor in the country’s politics. “Nigeria is only a geographical expression,” he said, quoting renowned politician Obafemi Awolowo from the south-west of the country. People of the same background tend to stick together because they “prefer the devil they know to the one they don’t”, he said. He added that the federalism enshrined in the Nigerian constitution tends to be abused by those in power, and that President Muhammadu Buhari’s government is no different. Buhari has appointed people mostly from the north of the country, resulting in accusations that he has marginalised people from the south-east and Niger Delta. Nigeria should never have been a country, he argues. The major ethnic groupings in the country are different peoples with different lived experiences, meaning that they tend to distrust one another.

Adekunle Salu, an author and retired public relations practitioner, agrees that ethnicity is still an important determinant of politics in Nigeria. Rational politics has been overwhelmed by regionalism and ethnicity. This has manifested in rampant nepotism and intolerance, since the country’s independence, he insists. The peoples of the south-west of the country had states—the Yoruba kingdoms, including the Oyo Empire—before the British arrived, he says. In other parts of the country, states such as the Kanem Borno Empire—which was never defeated by the British—also existed before the arrival of the colonialists. Social commentator and political activist, Tony Nwazeigwe, from the Nigeria Civil War and Genocide Research Network, agrees that ethnicity remains at the core of politics and governance in Nigeria, but he argues that more recently the focus has shifted from ethnicity to religion. He agrees that Buhari, a Muslim and a northerner, has mainly appointed northerners to federal roles, and argues that this has hinged his support to religion. The Nigerian government is increasingly active in Muslim organisations, including the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the Group of Eight Islamic Countries, and the Islamic Military Alliance to Fight Terrorism led by Saudi Arabia, and is attempting to borrow money from the Islamic Development Bank. All of this is incongruent with the provisions of Nigeria’s constitution which establishes Nigeria as a secular state, says Nwazeigwe, sharpening the Muslim-Christian divide in Nigeria, and placing the country’s secularisation “under very serious threat”. Nwazeigwe and his organisation are currently challenging Nigeria’s membership of these bodies in court.

Buhari’s frequent appointments of northerners have led to accusations from members of minorities that they are being marginalised, as well as suggestions that he is continuing the tradition of exclusive politics that failed to address issues that gave rise to the Biafran secession and the 1967-1970 Nigerian Civil War. David Okagbue, a former politician with the Action Congress Party of Nigeria in the south-east, says that ethnicity has taken a toll on development of the country. Qualities such as honesty, educational background, professionalism, integrity, patriotism and general merit have suffered at the hands of ethnic politics, especially with respect to government appointments. The result, he says, has been growing distrust among members of different ethnic groups, and a crisis of values. The recent tilt towards religious intolerance has further increased the marginalisation of minor ethnic groups, he argues. Arising from this, he observes that a rise in the number of ethnicity-related protests and demands for secession reflects factors that have previously undermined Nigeria’s developmental efforts. A range of organisations is seeking either self-determination or the political re-structuring of the country. Groups in the south-east, the hotbed of the Biafran Civil War, are presently agitating for secession from Nigeria. In the Niger Delta, the site of most of Nigeria’s oil production, a group called the Niger Delta Avengers is seeking resource control from a government it claims has not done enough to develop the region. In the Middle Belt, Fulani herdsmen-farmer conflicts have raged for decades. These have recently taken on a more murderous dimension, which has led communities to threaten to defend themselves.

Buhari is himself a Fulani. There is little evidence that he supports his kinsfolk in conflicts that have killed hundreds of people. However, his position as president may have emboldened some members of the Fulani to become more intransigent. Ikechi Emenike, politician and director of field operations for Buhari’s All Progressives Congress presidential campaign, says that many of Nigeria’s political parties have an ethnic colouration, though the former ruling party, the Peoples Democratic Party, can be said to have had a pan- Nigerian character. In his view, ethnicity is a more dominant influence within the country’s political parties than religion. In a recent scandal some members of the National Assembly were accused of abusing their power to locate constituency projects in their own towns or even on their own private properties. Meanwhile, Kano State has 44 local governments while Lagos, which has about the same population, has only 20. The south, a region with several minorities, has six states while the Igbo-speaking area has only five states. Both examples, Emnike suggests, indicate evidence of ethnic bias on the part of central politicians. Nevertheless, Nigeria has made some progress toward national integration. While Nigerians do bicker with each other, a Nigerian identity of sorts has developed in their interaction with outsiders. Its elements include values such as resilience, resourcefulness and pride. Moreover, the country has held five consecutive general elections since 1999 without ethnic conflagration. While the economy was strong during those periods, except towards the end of Goodluck Jonathan’s presidency, fears of recession and de-development have impelled Nigerians to close ranks.

The Nigerian elite united to wrest power from the British colonialists and win political independence in 1960. In the same manner, the threat posed by economic recession is gradually galvanising Nigerians to stand together to weather the hard times. The country’s diversification away from dependence on the oil industry offers many as yet untapped opportunities, including in agriculture, solid minerals and the tourism sector, for local and foreign investors. Political re-structuring and the emergence of a focused and less selfish leadership could unleash the vast potential of this beleaguered country.

Osita Agbu is Professor of International Relations and Dean, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences at Baze University, Abuja. He was formerly, Head, Division of International Politics at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), Lagos, where he worked for several years. He held both academic and administrative positions, serving as the editor of the Nigerian Journal of International Affairs (NJIA) for many years