Africa contributes less than 4% of global carbon emissions, but is bearing the brunt of climate change

The Group of Seven (G7) 47th summit was held in Cornwall in the United Kingdom from 11 to 13 June 2021. It was the first time since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic that the intergovernmental group of some of the world’s largest and most advanced economies have held the annual gathering to discuss, form agreements, and publish joint statements on major global issues. Joining the permanent members, which include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United States, and the UK, were Australia, India, South Africa, and South Korea as invited guests.

As expected, the primary topic of conversation for this year’s summit was to “beat Covid-19 and build back better”, with key pledges pertaining to securing and distributing vaccines to low and middle-income countries; strengthening global health and security systems to be better prepared for future pandemics; and reducing the borrowing costs of vulnerable countries to allow them to increase spending on health systems and cover pandemic costs.

The climate crisis also featured high on the agenda in anticipation of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) scheduled to take place in November in Glasgow. The members of the G7 reaffirmed their commitment to a “green revolution” and called on all countries to join their commitment to halving collective carbon emissions by 2030 in order to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees to above pre-industrialisation levels.

While it is unsurprising that most discussions pertained to the domestic commitments of G7 states, with the presence of South Africa one would have hoped that more attention would be given to Africa. After all, it is the continent most affected by climate change. In light of the competing energy needs, political realities, and developmental challenges facing many African states today, a robust conversation is required about how to finance a “green revolution” and ensure that such a transition is just.

International commitments versus local realities

To meet the goal of transitioning to net zero by 2050, the G7 states reaffirmed domestic promises pertaining to urgent and polluting activities, and general commitment to their respective Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – non-binding national plans highlighting climate actions across various sectors as a contribution to achieve the global targets set out in the Paris Agreement. In terms of the G7 states’ international commitments, the most notable included the “phasing out of new direct government support for international carbon-intensive fossil fuel energy as soon as possible, and an end to any new direct support for thermal coal power generation by the end of 2021, including through Official Development Assistance, export finance, investment, and financial and trade promotion.”

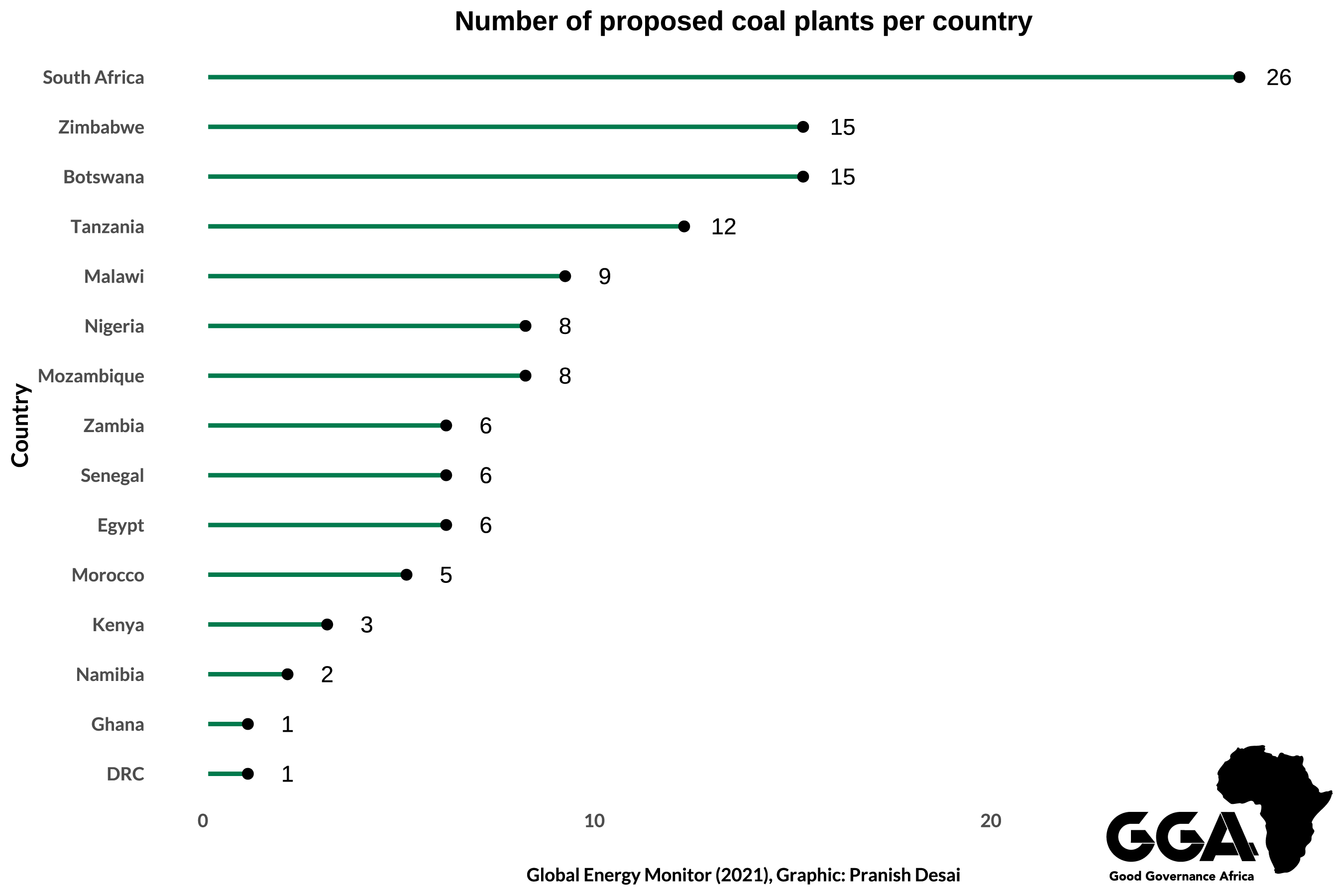

While European states are decreasing their dependence on coal, many African states are embarking on a massive expansion of fossil fuel electricity, with more than 200 new power stations planned, the majority of which will burn coal (see figure 1.1). In South Africa, for example, where persistent electricity supply problems have crippled the economy, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe recently called for 1500 megawatts in new coal generation exploration. This in contrast with Eskom’s (the largest producer of electricity in Africa) plan to decarbonise and repower coal plants using solar.

Figure 1.1

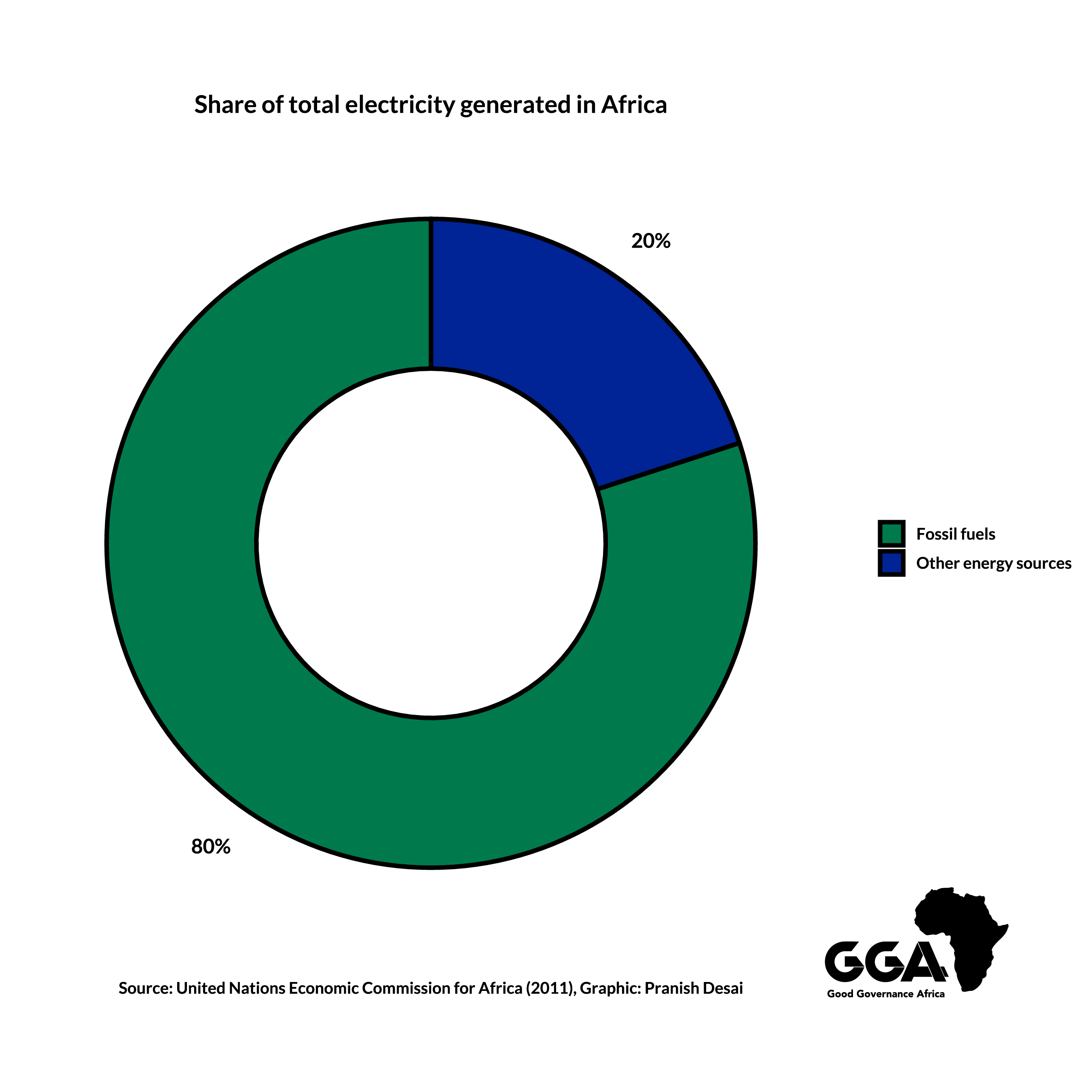

South Africa already tops the G20 countries in terms of reliance on coal for electricity ( 86% of the country’s electricity supply came from coal in 2020 compared with the global average of 34%). Fossil fuels still account for around 80 percent of energy supply across the continent (see figure 1.2.). However, efforts to switch to renewable energy in South Africa have been bolstered by President Ramaphosa’s decision to amend the Electricity Regulation Act, allowing companies to build their own generation capacity of up to 100MW.

Figure 1.2

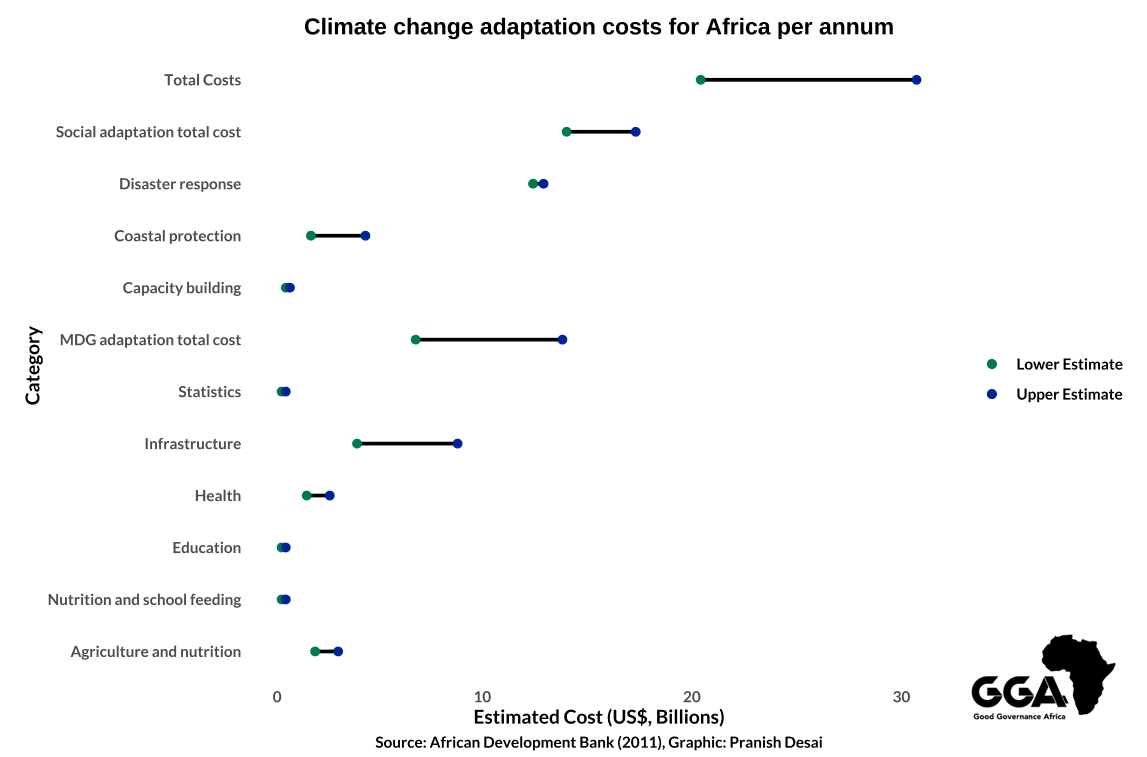

While the G7 “welcomed the work of the Climate Investment Funds (CIFs) and donors to commit up to $2 billion over the next year”, which is also expected to mobilise up to $10 billion in co-financing to support renewable energy deployment in developing and emerging economies, this is a drop in the ocean compared to what is needed in Africa, as shown in the graph below.

In fact, the G7 summit gave little indication that any new major financial commitments would be made to assist the developing world cope with the impact of climate change. In 2009, during the Copenhagen Summit (COP15), developed countries agreed to contribute $100 billion to assist poorer countries to cope with climate change. To date, the money is yet to be realised. The goal was again reiterated this year by the G7 who “resolved to deepen our current partnership to a new deal with Africa”. However, there is little indication of how this money will be raised, particularly given the impact of Covid-19 on the availability of development funding.

Moving forward: COP26

Despite the efforts made by some countries, finance remains a significant challenge in tackling climate change in Africa. To date, the financial resources jointly contributed by developed countries have been inadequate in assisting Africa’s adaptation and mitigation efforts. Member states of the Paris Agreement must provide additional financial resources to support climate action, as stated in the UNFCCC article 4.

According to the African Development Bank, Africa requires an estimated $20-30 billion per year until 2030 to assist climate action. African states should press for more funds to adapt to the impact of climate change and not merely allow developed states to redirect resources and recite promises. At the same time, African countries need to present clear plans, integrated with development plans, on how they will utilise the money.

The importance of Africa in COP26 should not be underestimated. What is required is a unified African voice that will advocate for African development. Africa contributes less than 4 percent of global carbon emissions but is bearing the brunt of climate change impacts across multiple sectors.

The high vulnerabilities and low adaptive capacities of many African states to climate change is already thought to be driving a rise in conflict incidents in some regions of the continent and exacerbating existing resource-based ones. Several studies show that Africa’s agricultural productivity is likely to decline in coming decades as a result of climate changes, ultimately affecting food security, and without significant investment in adaptation and mitigation strategies, Africa’s growth and development prospects are certain to be negatively impacted. As such, African negotiators must assert the importance of major carbon emitters significantly cutting their emissions. African negotiators must be prepared to challenge Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC)that fail to acknowledge their part in climate impact and fail to address African gripes.

Leleti Maluleke is a Researcher for our Human Security and Climate Change programme. She completed her Bachelor of Political Science in Political Studies in 2017, and her Honours in International Relations in 2018 at the University of Pretoria. She started her career at International SOS in the Security Services department as a Political Risk and Security Intern. Socially, her countries of interests include Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi.