Good and inclusive governance is critical for Africa’s economic growth

Africa is on the rise. In 2018, it was the world’s second fastest-growing region, experiencing an average annual GDP growth of 4.6% for the period from 2000 and 2016. For the five-year period until 2022, Africa’s real GDP is projected to grow at 3.9% annually. The African Development Bank says that the continent’s economic growth could rebound to 3% in 2021 from -3.4% in the worst-case scenario for 2020, provided governments manage the COVID-19 infection rate well.

Speaking in June 2020 at the Centre for Global Development’s virtual event, Conversations on COVID-19 and Development, Vera Songwe, the executive secretary of the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) said Africa had to remain awake and take appropriate measures to help find solutions to the pandemic and its impact.

“Although Africa has experienced a substantial downturn, with growth falling due to a number of reasons, including the disruption of the global supply chain, governments on the continent have taken measures, including putting in place policies and programmes that support inclusive and sustainable post-pandemic recovery that will help the continent to grow back and build back better”, she said.

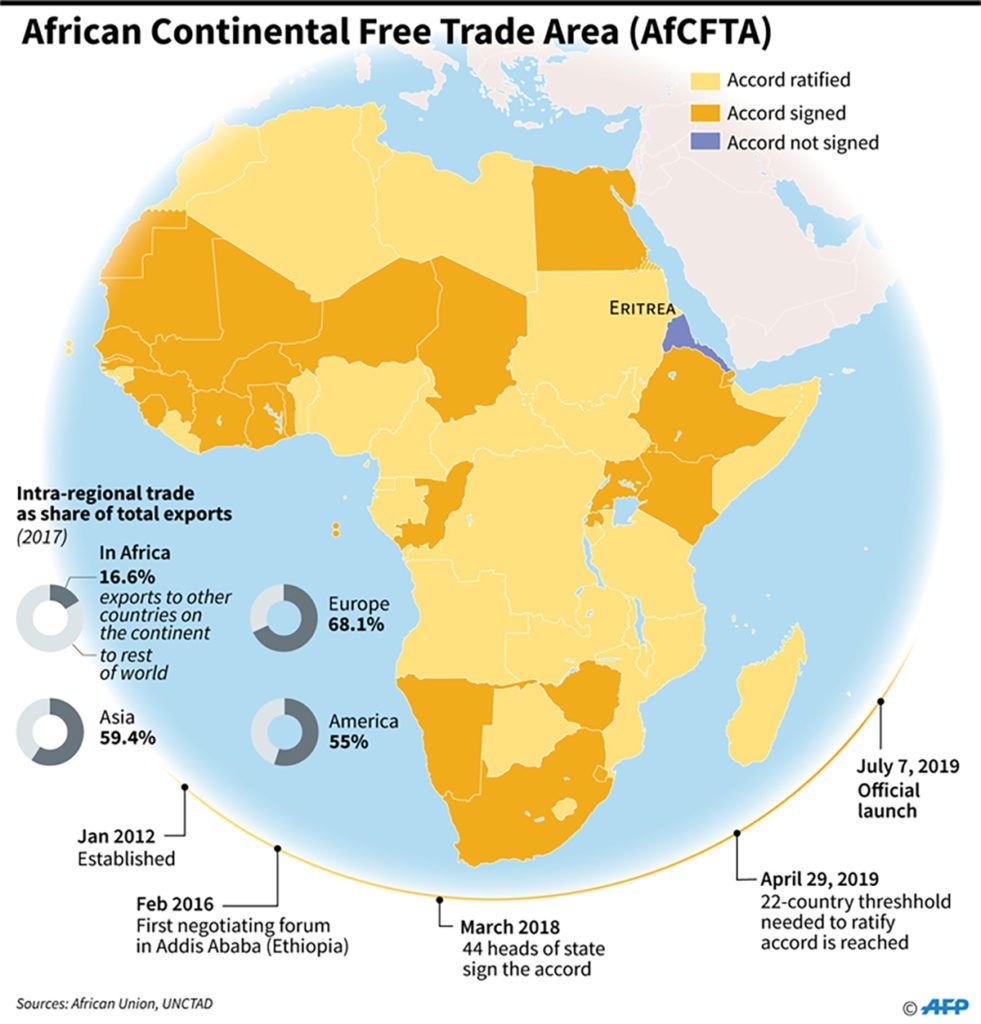

The African Heads of States and Governments pose during African Union (AU) Summit for the agreement to establish the African Continental Free Trade Area in Kigali, Rwanda, on March 21, 2018. (Photo by STR / AFP)

Africa has had to shake off the dire socio-economic legacies inherited from colonialism (the creation of arbitrary borders, single crop economies, an over reliance on the export of extractives and the creation and support of elites, encouraging corruption, to name a few).

As Nigeria’s former minister of state for labour and employment Stephen Ocheni argues, colonialism institutionalised poverty amongst Africans; the aim of colonial powers was to extract resources with little concern for livelihoods or quality of life. Also, colonial rule was by state domination rather than legitimacy, an authoritarian political culture that controlled people using violence, patronage and corruption.

But now, successive African governments have recorded steady growth in GDP, ranking well globally in their population’s access to basic services and improvements on the Human Development Index (HDI), which measures life expectancy, education and income.

African countries are also rapidly plugging into the global economy due to its natural resources, digital innovations, technology driven change and a positive shift towards the fourth industrial revolution, which has unlocked new pathways for rapid economic growth, innovation, job creation and access to services.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) also notes, for example, that there has been “remarkable progress” since the transition to democracy, spurred in part by the end of the Cold War, which has seen post-colonial authoritarian regimes challenged across the continent, especially by youthful populations, and the emergence of competitive multi-party systems since the 1990s. There is progress in a number of countries in Africa, not only with regard to growth and poverty reduction, but also in terms of reductions in extreme poverty and increases in education enrolment.

As the UNDP’s Human Development Report 2019 has noted, African countries have made significant strides in advancing human development – narrowing the gap in basic living standards with an unprecedented number of people escaping poverty, hunger and diseases.

But, as Songwe emphasised, good governance is essential for sustainable development and progress. “There is growing consensus that African countries require a more conducive governance environment for them to be able to pursue better public policies, and ultimately to achieve better outcomes, including structural transformation and inclusive development,” she said.

The continent still has significant ground to cover in terms of improving governance for prosperity. A number of countries, including Angola, Central African Republic (CAR), Republic of Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Sudan, and Somalia, among others, are yet to design governance models that can prevent dictatorship, corruption, and economic decline.

Angola’s leader, João Lourenço, who succeeded Jose Eduardo dos Santos in 2017, initially made some progress in ending the patronage system entrenched by the dos Santos family, but further efforts have stalled. However, these countries still score poorly on human rights protection and the provision of welfare to their populations.

Ongoing post-colonial sectarian violence and ethnic and religious tensions have also hindered attempts at better governance, encouraging weak and ineffective leadership and a fear of the transformation that underpins separation of powers, with checks and balances. CAR, Somalia, Eritrea, South Sudan and lately, Ethiopia, continue to suffer sectarian conflicts partly emanating from the legacy of their liberation struggles.

A crucial ingredient in improving human development is wealth creation, which requires the existence of an entrepreneurial class; without sufficient peace and security, a culture of entrepreneurship cannot thrive. Countries such as DRC and South Sudan, despite their huge economic potential due to minerals and oil, have paid heavily for the absence of the rule of law to contain ethnic-induced violence.

Porous and unviable African borders, improperly designed by colonial powers, have caused instability and conflict in many parts of the continent, including West Africa, the Great Lakes region and the Horn of Africa.

“To make greater economic progress,” Ocheni says, “Africa must confront its past, and with its leaders and the people they govern create their own identity, culture, technology, economy, education, religion, craft and other key aspects that underpin good governance.”

As Christopher Clapham, a professor of African Studies at Cambridge University, noted in a paper ‘From Liberation Movement to Government’, published by the Brenthurst Foundation in 2012, the experience of struggle has generally been regarded as an enormously positive legacy for the new states, even though “virtually all liberation movements have encountered myriad difficulties in making the transition from struggle to government”.

Clapham pointed out, however, that demographics typically shift the power balance after a period of time. “High birth rates and correspondingly young populations mean that within a couple of decades of liberation, most of the population will have no personal memory of the struggle at all, and calls by members of the ruling party to remember their heroic contributions will simply fall on uncomprehending ears,” he says.

He concluded by saying that while the road to liberation was long, it allowed for the “possibility of eventual reconciliation between the aspirations expressed in struggle on the one hand, and the need for stable and accountable governance on the other. … In some cases, liberation movements turned nascent government have helped to meet popular demands for employment and public welfare and established national identity, national integration and reconciliation.”

Paul Nantulya, a research associate at the Washington-based Africa Center for Strategic Studies, says that “even when founded on noble principles and objectives, successful liberations are not a guarantee of successful democratic transitions. “Legitimacy conferred by the struggle tends to foster a sense of entitlement to rule. The culture of entitlement can become pervasive, leading to a cult of personality where the movements are embodied by a single individual,” he says.

Countries in crisis must engage in process-driven constitution-making that values the separation of powers, with effective checks and balances, robust and politically active civil society. An independent judiciary and press are also crucial tools of good governance.

These efforts should also address emerging global challenges such as climate change and pandemics. Regional cooperation and affirmative action among historically marginalised communities such as youth, have become hallmarks of today’s constitutions.

Finally, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into force on 1 January this year, provides a good template to promote good governance among countries on the continent. The AfCFTA is expected to provide many opportunities, including creating a single continental market for goods and services, with free movements of business, people and investments.

Raphael Obonyo is a public policy analyst. He’s served as a consultant with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). An alumnus of Duke University, he has authored and co-authored numerous books, including Conversations about the Youth in Kenya (2015). He is a TEDx fellow and has won various awards.

It is quite clear that bad governance has stalled both social and political progress in most African countries.

I hope we as Africans open our eyes to the great potential we possess and take actionable steps towards implementing values that promote good governance.