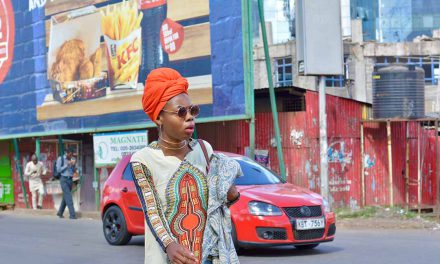

The African story abounds with great women whose achievements are often reduced to prurient anecdotes

Until lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt shall always glorify the hunter. So, says the Igbo proverb, which became a rallying cry for a generation of post-colonial African historians. But what of the lionesses? Are their tales being told? But enough with animal adages. Neither lions nor lionesses write history, while people do. The key question is: do the current written histories of Africa adequately include the experiences of the continent’s women?

Depends where you look. And who you ask. Since the 1960s, the university-based study of African women’s history has become a dynamic, global field. Where once the economic, social and political contribution of African women was regarded as an historical terra nullius – with women either entirely absent or relegated to minor roles in textbooks and tomes – there is now an ever-increasing body of research that includes analysis on a wide variety of societies, over 50 countries and hundreds of thousands of years.

Academia is acknowledging that African women enter the historical narrative from a variety of geographies and climates and that they carry diverse status, education, culture, age and other attributes. Moreover, all of the above can change or stay the same or circle through a combination of both within the endless ebb and flow that is human life and lives over time.

Academic historians recognise that what they study is not the past per se but rather an interpretation of the past, which is subject to revision and reinterpretation whereby distinct interest groups apply different standards, priorities and values and reach different conclusions. There is general consensus that interest groups with more social, political and economic clout have the power to dominate the narrative.

There is now widespread acknowledgement that the gendered nature of modern power is such that male stories are disproportionately present and that women’s stories are often assigned less value. The growth of African women’s history as a discipline demonstrates that spaces can and have been created to examine and challenge such power dynamics.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that almost all such scholarship sits behind paywalls on university websites. Non-professional historians are largely excluded from this information and the debates that such study stimulates. Outside of ivory tower academe, what passes for historical “knowledge” in the general chitchat of daily life more often than not either ignores them entirely or depicts women in terms of their perceived impact on men.

Historical evidence of African women is as old as humanity. Sometimes older. Humans evolved in Africa and so it is Africa that provides the backdrop for the first minimising of prehistoric women in the paleoanthropological corpus. Until the early 1980s archaeologists overlaid modern Western gender norms and sexual divisions of labour onto pre-historic, sometimes pre-human hominid peoples. Man the Hunter was widely considered to be the key evolutionary driver of human brain development and subsequent tool-making innovation.

Frances Dahlberg’s 1983 monograph, Woman the Gatherer, set forth a strong case for an alternative evolutionary trajectory in which Woman the Tool Inventor played an equal part in the human story. Which is all well and good – but for the fact that, over three decades later, that message doesn’t appear to have gotten through to the masses. Museums are the point at which the public and professional historians ought to intersect, but Africa’s pre-historic women are all but invisible at such sites. Androcentric stereotypes abound. Almost invariably, graphic material explaining the hominisation process depicts individuals of the masculine sex making their way from australopithecine to homo – thereby rendering the earliest African women invisible.

As Myra and David Sadker argued in Failing at Fairness (1995), “each time a girl opens a book and reads a womanless history, she learns she is worth less.” How much more so if she isn’t even in the diagram exploring the essence of our species?

Yet it is debatable as to whether exclusion is preferable to defamation. African women who achieved scientific, political or economic success have often been pulled into warped morality tales masquerading as history, which reduce a plethora of complex characters to wicked women who drew men into their beds and on into their death. The deeds of women in times past are subjected to such treatment worldwide but the practice seems particularly prevalent when it comes to telling tall tales about successful African women, who are almost invariably subjected to what amounts to a form of “ye olde” slut shaming. The accompanying character assassination is seldom supported by the sort of historical evidence-based scholarship found on the other side of the paywall.

Consider Cleopatra. Mary Hamer’s Signs of Cleopatra: Reading an Icon Historically (2001) offers us vast quantities of contemporaneous written records demonstrating the diplomatic, naval, linguistic, cultural and philosophical skills of Cleopatra VII Philopator (69-10 BC), the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. Her tenure alone speaks to such skills. She ruled for 21 years and at the height of her power controlled virtually the entire eastern Mediterranean coast. She was incomparably richer than anyone else in the region. And yet she survives in the popular imagination through a distorted depiction of her romantic relationships. She built fleets, suppressed several insurrections, controlled a currency and guided a nation through plagues and famines but she is remembered as a bare-breasted seductress bathing in milk.

Linda Heywood and Louis Madureira’s 2015 article, Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620-1650 offers chapter and verse on their study subject’s skills as a military leader, strategist, diplomat and exponent of realpolitik par excellence. Research reveals the woman who defined and dominated what is now Angola in the 17th century to be a complex and contradictory character. At times, she profited from the trans-Atlantic slave trade, while at other times she protected escaped slaves. For over 40 years, she successfully limited the Portuguese colony at Luanda to a few square kilometres. How is it that her achievements are less well known than gratuitous and unsubstantiated gossip about her immolating a harem of male lovers?

Publicising the achievements of African women from previous generations has the potential to impact on the development of self-respect for African girls and women going forward. There is inspiration in knowing about the trials, tribulations and triumphs of Asante-born Nanny of the Windward Maroons (c.1686 – c.1755) who escaped from slavery in Jamaica, led a successful armed rebellion, freed more than 1,000 previously enslaved people and achieved a 1740 peace settlement with colonists, under the terms of which she negotiated a land grant of 500 acres at what became known as Nanny Town.

In the face of Boko Haram’s terror and intimidation tactics, which threaten girls’ access to education across West Africa, there is strength to be drawn from knowing that in 859CE an African woman, Fatima bint Muhammad Al-Fihriya Al-Qurashiya, founded the University of Al Quaraouiyine in Fes, Morocco. UNESCO describes it as the oldest existing, continually operating and first degree-awarding educational institution in the world. Female alumni include Fatima al Kabbaj, member of the Moroccan Supreme Council of Religious Knowledge.

At its most pernicious, observations of a past that never was are used to support patriarchal practices that exclude women from power in the present. During Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s 2016 visit to German Chancellor Angela Merkel he responded to a question about his wife’s political opinions with the comment that, “I don’t know which party my wife belongs to, but she belongs to my kitchen and my living room and the other room” because he could “claim superior knowledge over her”.

At its most pernicious, observations of a past that never was are used to support patriarchal practices that exclude women from power in the present. During Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s 2016 visit to German Chancellor Angela Merkel he responded to a question about his wife’s political opinions with the comment that, “I don’t know which party my wife belongs to, but she belongs to my kitchen and my living room and the other room” because he could “claim superior knowledge over her”.

Indeed, 2016 was a banner year for Nigerian patriarchal put-downs. In the same year, that country’s senate rejected a Gender and Equality Bill that included equal rights for women in marriages, divorce, property ownership and inheritance. Several senators stated that they opposed the law on the grounds that it was “un-African” and “anti-religious” to accord women equal rights with men.

Such statements invoke tradition, but the historical record shows otherwise. Kamene Okonjo’s studies of women’s political participation in Nigeria show that pre-colonial West African women were often much more economically, socially and politically independent and powerful than modern “traditionalists” would have us believe.

Their disempowerment came about by way of colonial Eurocentric, not indigenous African values. Chima J Korieh’s Gender and Peasant Resistance: Recasting the Myth of the Invisible Women in Colonial Eastern Nigeria, 1925-1945 (2003) offers evidence that while Nigerian women had historically participated in the government, the British colonial authorities saw these practices as “a manifestation of chaos and moral disorder” and would only engage with the political institutions headed by men.

Struggles over alternative views on the desirability of female political and economic power sparked significant anti-colonial revolts, including what modern historians tend to call the Women’s War of 1929 (Ogu Umunwanyi in Igbo), which was described by colonial authorities as the Aba Women’s Riot.

A watered-down version of the Nigerian Gender Equity Bill was subsequently passed in 2017 but the claiming of tradition to support female subjugation illustrates how a patchwork of patriarchies can cross the hunter/lion duality. There are times when hunters and lions form alliances around their common predator paradigm and call on faux history in support of shared interests. As we recognise and rectify the exclusion and misrepresentation of female African lives from the study of history, let us take cognisance of life’s complexity.

Even if certain sorts of lions and lionesses now have/are historians, accounts of their times past are likely to be incomplete unless the experiences of the earthworms and the elephants and the E.coli are included. Not to mention the valuable perspectives provided by the trees and the reeds. And the wind and the rain. Ultimately, ours is an interdependent ecosystem.

Dr Anna Trapido is an anthropologist and a chef. She trained as an anthropologist at King’s College, Cambridge, completing her PhD in the department of community health at Wits University, Johannesburg. She qualified as a chef at the Prue Leith Chef’s Academy in Pretoria, and uses both disciplines in her work. She has won gold at the World Gourmand Cookbook Awards three times (for To the Banqueting House - African cuisine an Epic Journey, Hunger for Freedom – the story of food in the life of Nelson Mandela, and Eat Ting – lose weight, gain health, find yourself).