In a historic US election, President Donald Trump was ousted from office by Joe Biden. Biden won 50.8% of the popular vote, while Trump still managed 47.5% in the largest voter turnout since 1908. The presidency of Donald Trump is widely viewed as anomalous, a monstrous blip in an otherwise healthy and deeply consolidated democracy. This would be a mistake. A deeper analysis reveals that populism can take root even in societies with relatively broad-based access to political and economic opportunities.

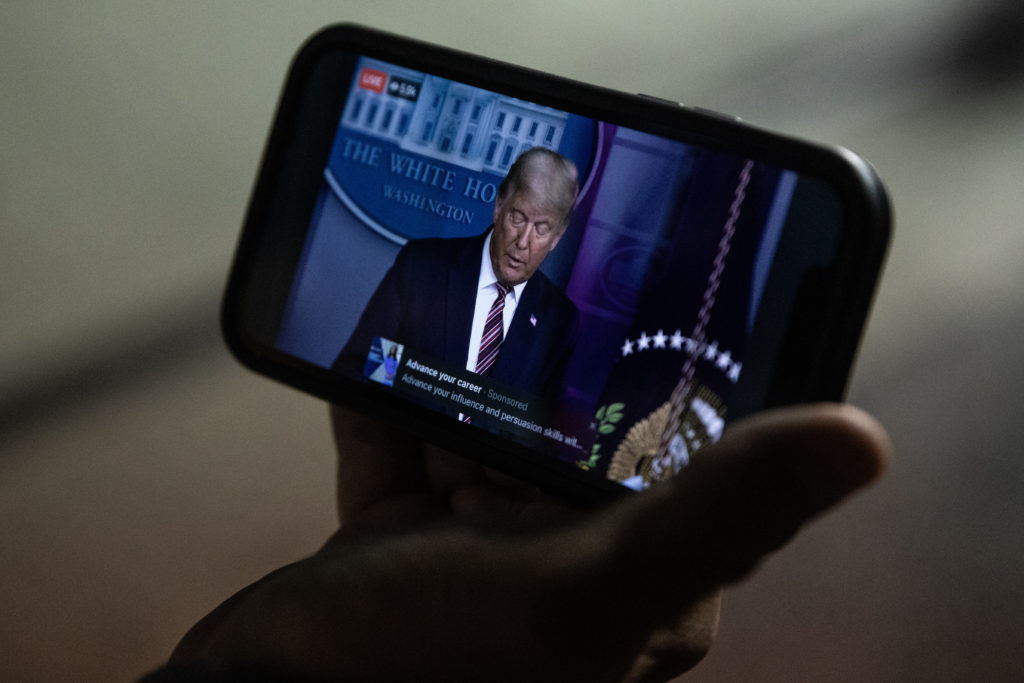

A man participating in a protest in support of counting all votes watches U.S. President Donald Trump hold a news conference as the election in the state is still unresolved on November 5, 2020 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. With no winner yet declared in the presidential election, all eyes are on the outcome of a few remaining swing states. Chris McGrath/Getty Images/AFP

Globalisation, accelerating apace since the end of the Cold War in 1989, has resulted in a highly uneven distribution of the gains from trade and volatility from easy flight of capital. While global GDP has ballooned, inequalities have widened, with real income growth among the top quintile rapidly outpacing middle class wage growth. Local displacement has intensified. Outsourcing or automating jobs in the name of economic efficiency has created political ruptures in historically strong democracies. These dynamics have ploughed the soil for populism to take root. The populist playbook is to exploit the fears and disappointments of the economically marginalised and subvert democratic institutions in the process.

Trump’s tantrums over alleged vote-rigging and repeated court threats are simply part of the script. The phenomenon of democratic backsliding has so arrested the attention of scholars that between 2011 and 2018 alone, 1,700 academic articles were published on the subject. In the 40 years prior, a total of 1,500 articles covering threats to democracy appeared. The fact that Biden has won out against Trump may provide some reprieve for friends of democracy across the globe, but complacency is unwarranted. Otherwise strong democratic equilibria tend to be disrupted by socio-economic inequality, financial shocks, the exploitation of extreme political views by technological interference (read Cambridge Analytica) and the resultant perpetuation of echo-chamber social-media politics.

None of these trends show any sign of abating. Worryingly, they are also mutually reinforcing, which can create path-dependent trajectories away from democracy. As scholar Daron Acemoglu has pointed out, the global factors that have contributed to growing domestic inequality in the US have not been addressed, and policymakers are far from a consensus on how this can be done. Biden’s work is cut out for him to forge bi-partisan agreement that, for instance, higher federal minimum wages and a more redistributive tax system may be desirable. Even with that in place, though, the global trend towards distrusting scientific facts and resenting elites is strengthening. Populism thrives in such contexts.

Perhaps the most concerning element of Trump’s ascendancy was the willingness of Abraham Lincoln’s 150-year-old party to acquiesce to Trump’s proposition to ride on a Republican ticket. And, typical of populist incoherence, most of what he stood for and campaigned on were diametrically opposed to orthodox republican positions such as free trade. Nonetheless, as one commentator put it, Biden has ‘sleep-walked’ into the White House and the embers of democracy are still alive in the US. Notwithstanding the warning to avoid complacency, it remains good news because, on average, democracy causes economic growth. Why? Because its ability to remove leaders like Trump is one of its enduring attractions.

Consolidated democracy, for all its inefficiencies, respects the rule of law, insists on the separation of powers, punishes corruption, and gives the citizenry a voice that produces proper accountability from the elite. This institutional strength, in turn, results in economic dynamism, as contracts are honoured and businesses can flourish. Responsible players are crowded in while irresponsible players are either crowded out or deterred from engaging in corrupt activities. In a nutshell, good governance is more likely to take root in the context of robust political competition where the opposition has a fair and credible chance of winning elections.

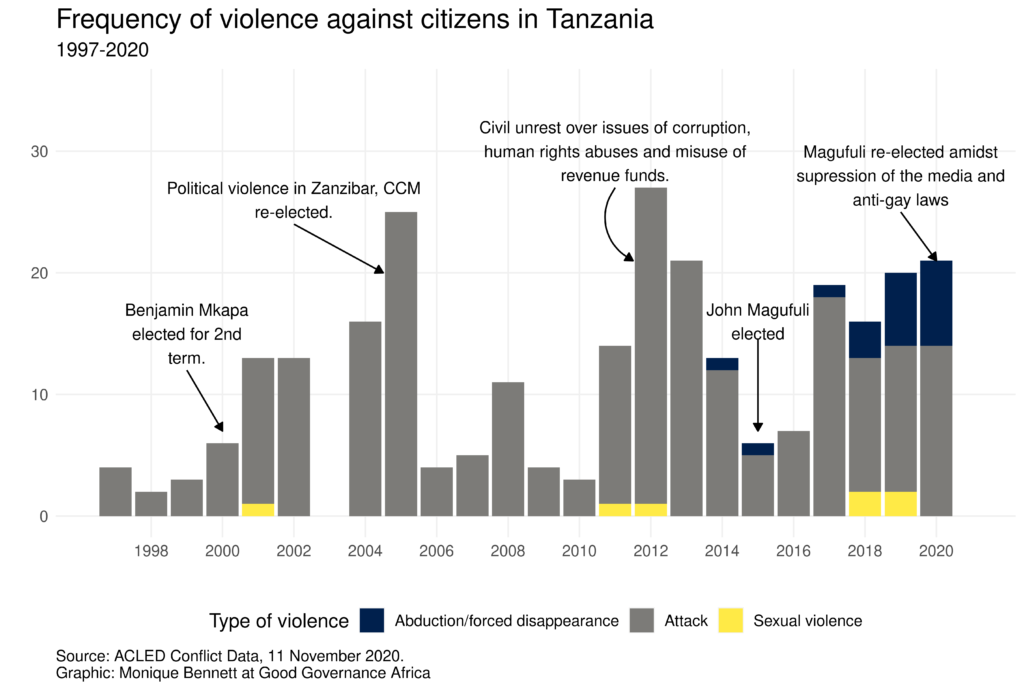

While the world breathes a momentary sigh of relief, African countries continue to fight for democracy to take root at all, never mind worrying about whether it will consolidate. While the evidence suggests that democratisation across the continent is advancing, on average, a number of important red flags punctuate the trend. Tanzania, soon to be among the most populous countries on the continent, held its general elections on 28 October 2020. Incumbent President John Magufuli successfully rigged the process to secure for himself an incredible 84% of the vote while the main opposition managed to eke out 13%. According to the Polity V dataset, the country’s democratic score improved from 2 (out of a possible 10) to 4 from 2014 to 2015 (the year in which Magufuli came to power).

We expect that figure to move below zero once the next set of figures is released. Not only did Magufuli rig the elections, he has ruled with an iron fist of fear, initially rooting out some petty corruption – his populist ticket – but he has since crushed civil liberties and shut down opportunities for opposition parties to engage in politics. Post-election, Tundu Lissu, chief opposition leader who survived an assassination attempt in 2017, has had to flee the country after calling for protests against the election results; this in the midst of reports that at least 150 opposition leaders and members have been arrested since 27 October, with at least 18 remaining in custody. The frequency of abductions and/or forced disappearances has ticked up significantly since Magufuli came to power.

Economic growth has been sclerotic under Magufuli’s rule as he continues to be suspicious of the private sector and insists on white elephant megaprojects such as the Stiegler’s Gorge hydropower project that the country cannot afford. GDP per capita growth initially fell to 3% in 2015 (from 3.6% the year before) before recovering to 3.7% the following year. It has since fallen to 2.7%.

Magufuli came to the presidency from a weak base within the CCM – the liberation movement of Julius Nyerere – and is working hard to purge elites from within his ruling coalition who would otherwise ensure some degree of power-sharing. There is every reason to expect that Magufuli will attempt to clinch a third term in office, which would violate the constitution. He would join a long list of those who long ago eschewed term limits, a fundamental governance limit on executive power. A fundamental problem is not only that autocratic rule tends to result in misery and squalor for the majority, but that governance-dismantling autocrats seem to spur each other on across borders.

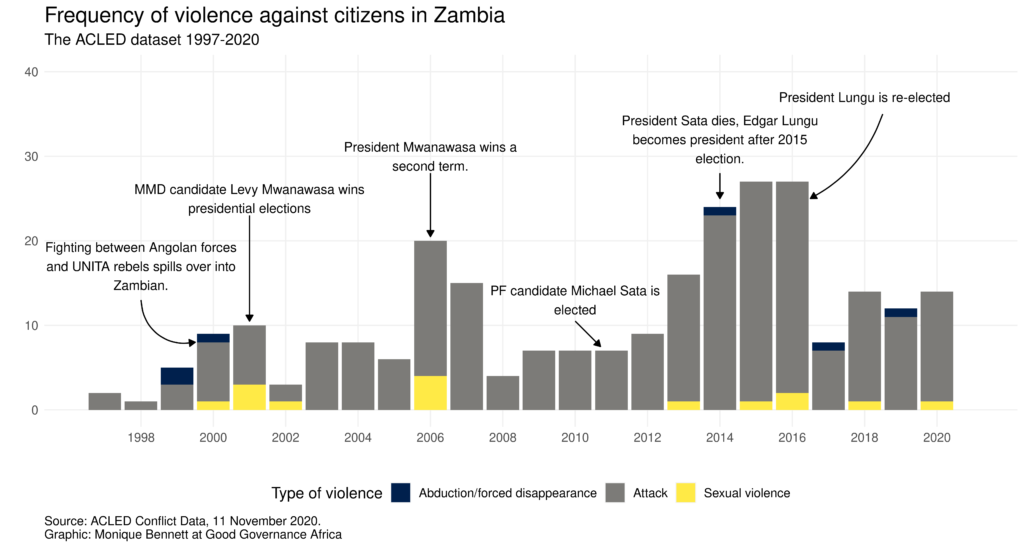

Zambia’s elections are set for 2021, and President Edgar Lungu appears to be taking a leaf out of the Magufuli playbook but with some variety to spice up the mix, drawing on Emmerson Mnangagwa’s Zimbabwean script too. It appears that his strategy for rigging the elections is to amend the constitution to allow coalition formation (instead of a runoff second ballot between the top two candidates) in the case of no candidate winning more than 50% of the vote. He brought this infamous “Bill 10” to parliament at the end of October but it failed (though by a margin of only 6 votes). At least this strategy indicates that Lungu is scared of losing the popular vote and does not have Magufuli-like power to simply rig the election to an arbitrary winning proportion of his pre-selected choice.

The opposition has a strong likelihood of winning the election, though Hakainde Hichilema – the leader of the opposition – is undoubtedly keen to avoid more jail time at the hands of Lungu’s trumped-up charges (as has happened before). Analysts expect that Lungu, on failing to win Bill 10, will now simply abolish the current voters’ register and create a new one more favourable to his prospects. The graph below indicates a surge of violence around the 2016 elections that saw Lungu gain a second term in office. As Natasha Chilundika has written over at Democracy in Africa, we really need to avoid a repetition of this come 2021.

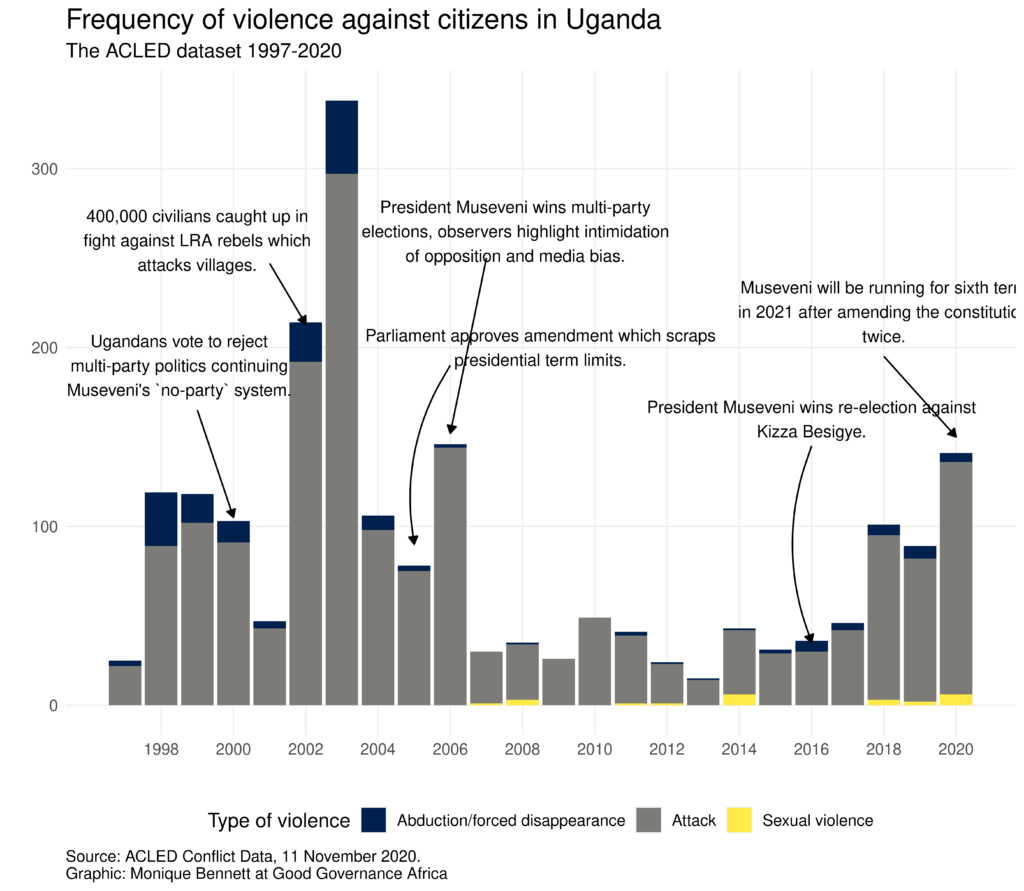

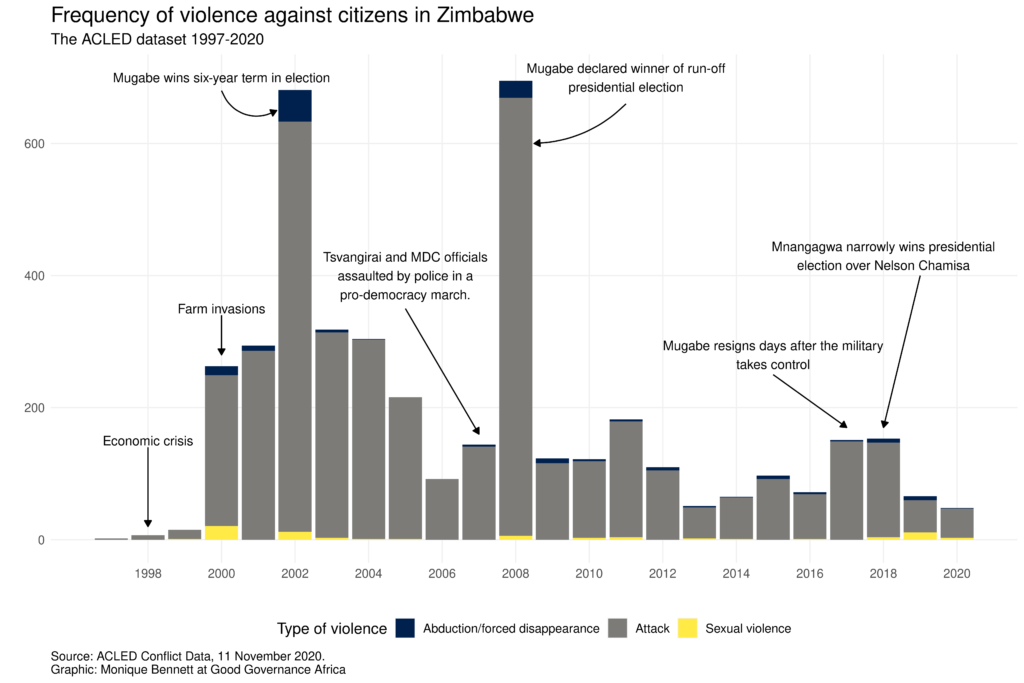

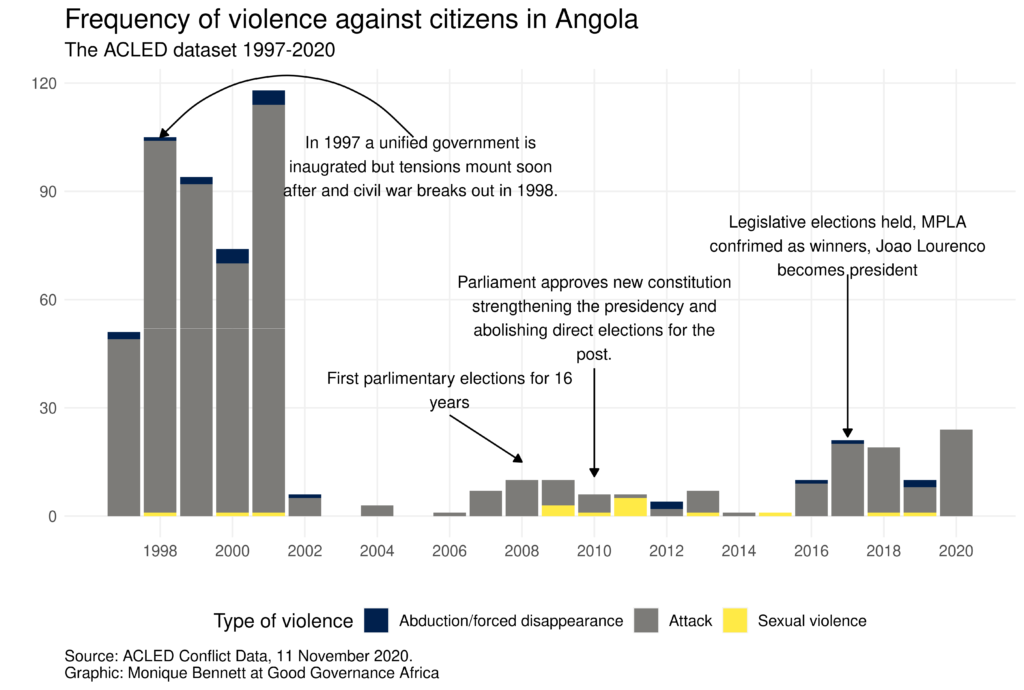

Slightly further afield in Uganda, President Yoweri Museveni has been in power since 1986. Still going strong, according to scholar Moses Khisa, Museveni has “run roughshod over important constitutional and institutional safeguards, checks and balances that were enshrined in what was a relatively progressive and liberal [1995] constitution”. Museveni is edging in on the 38-year rule exercised by Jose Eduardo dos Santos of Angola, and the 37-year reign by Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (both upended by their own ruling coalitions in 2017). Museveni’s assault on democracy began in 2003 with an eradication of constitutional term limits.

In addition to subverting apparently democratic institutions to advance authoritarian ends (by co-opting and corrupting the judiciary, for instance), he has also used external security threats as a cover under which to criminalise otherwise legitimate political activities. Museveni has had Kizza Besigye, his main opposition, arrested more than 1,000 times. A period of relative calm prevailed between 2007 and 2013, but violence against citizens has been on the rise, with incidents this year alone matching the 2006 data. The prospect of commercial oil revenues will further embolden Museveni’s autocratic stranglehold through enabling him to distribute patronage to a carefully selected circle of insiders and repress outsiders.

On the subject of Mugabe and dos Santos, their removal tells an important story. Autocrats who successfully consolidate power are almost always only removed by an internal coup or death in office. Very few in contemporary history have been upended by democratic forces. The risk of further autocratic consolidation is, therefore, immediately at hand. In Russia, Joseph Stalin’s death did not suddenly usher in democratic rule. Vladimir Putin’s stranglehold over the ruling coalition in Russia today is evidence enough to show that new autocrats are likely to gain ascendancy and the fight for democracy to take root requires far more than the removal of one autocrat. It requires the slow, hard work of establishing governance institutions that respect the rule of the people by the people.

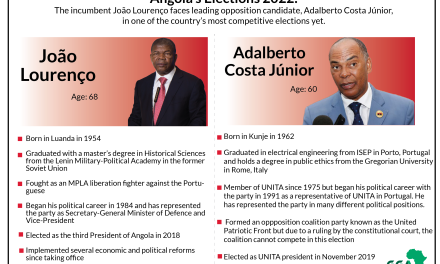

In both Zimbabwe and Angola, new autocrats have arisen. Mnangagwa and Lourenco respectively came to power through removing their long-standing leaders who had placed family members ahead of party loyalists, threatening their access to power and rents. One may have expected that some kind of power-sharing mechanism would be re-established in both Zanu-PF and the MPLA respectively, but there is little cause for optimism on the basis of the current evidence. Both incumbents enjoy vast access to resource wealth, again enabling the distribution of rents to a select circle of loyalists and careful elimination of internal and external threats to their rule.

Citizen attempts to protest against grand corruption in Zimbabwe around July this year resulted in a rapid rise in disappearances, abductions, torture and arrests – these have not yet been captured in the data below, but the graph still paints a terrifying picture of the militarised regime’s willingness to exercise repression to prevent any accountability. With elections set for 2023, we can either expect to see further violence escalation or an indefinite postponement of elections altogether.

A similar pattern emerges from Angola, with violence against citizens increasing again in the aftermath of the 2017 elections that saw Lourenco come to power through a rigged election. Unlike Magufuli’s CCM, though, the MPLA chose a winning figure of nearer to 60% than 80%.

For all one might say about the Trumpian episode in US politics and its dangerous flirtation with autocracy, the fact is that the vote matters in the US and Trump is out (or at least probably will be with Republicans now also losing patience with his intransigence). Americans have exercised their voice. Moreover, no matter whether one resonates with Kamala Harris’s political views, it is a significant feat that an African-American woman has ascended to the White House (and the first woman vice-president in US history) despite so much underlying racial tension in the country.

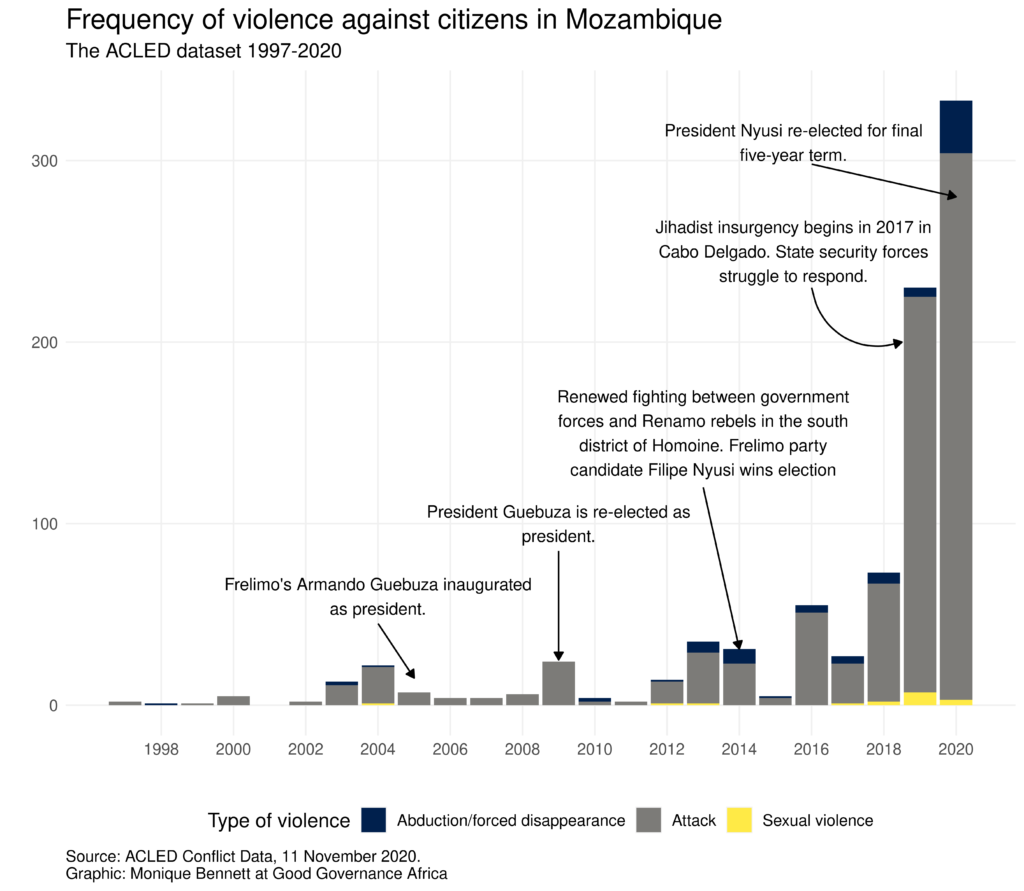

It is easy to be despondent about the deep structural divides that threaten to disrupt the US democratic equilibrium, but the fact that it has stood firm should encourage us to war against the proliferating autocratic threats to democracy in many African countries. Of course, the continent is not without hope, and the general trend is arguably positive. But it would be amiss of us to ignore the warning signs in Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe, not to mention Ethiopia (in which the risk of a full-blown civil war escalates daily), the DRC, Nigeria and Mozambique. Mozambique, in the context of poor governance, deep local grievances and a poverty trap, is fertile soil for the rise of violent extremism. It’s an explosive cocktail that risks spilling over into neighbouring countries.

One recent light in these otherwise dark trajectories, though, is Malawi. Small and poor, for sure, the country is wracked by a history of corruption and extensive poverty. Nonetheless, when Lazarus Chakwera came to power earlier in 2020, in the midst of a global Covid-19 pandemic, he showed that it is possible for the judiciary to stand firm against an incumbent executive bent on staying in power and for the people to vote that president out in an election re-run. This should be celebrated loudly, if cautiously, and remind us that it all starts with governance.

As Dr Grieve Chelwa has quipped, SCOTUS might do well to cite the Malawian court case should Trump successfully get to the Supreme Court over his allegation that the US election results were rigged. We should never give up in our quest to build governance institutions that prevent the abuse of power and give the people a voice.

Dr Ross Harvey is a natural resource economist and policy analyst, and he has been dealing with governance issues in various forms across this sector since 2007. He has a PhD in economics from the University of Cape Town, and his thesis research focused on the political economy of oil and institutional development in Angola and Nigeria. While completing his PhD, Ross worked as a senior researcher on extractive industries and wildlife governance at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), and in May 2019 became an independent conservation consultant. Ross’s task at GGA is to establish a non-renewable natural resources project (extractive industries) to ensure that the industry becomes genuinely sustainable and contributes to Africa achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Ross was appointed Director of Research and Programmes at GGA in May 2020.