Kenya African National Union makes a comeback

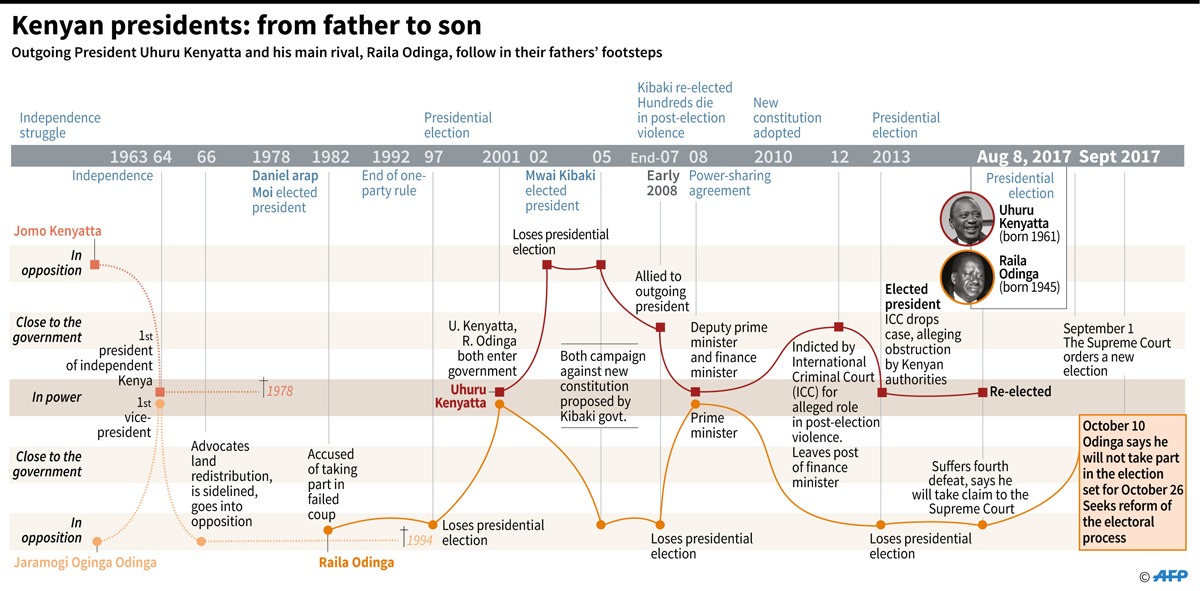

In 2002, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), the ruling party in Kenya since independence from Great Britain in 1963, fielded a relative greenhorn as its presidential candidate, the son of the first president Jomo Kenyatta, Uhuru Kenyatta. But the ruling party was outvoted by a strong opposition, the National Rainbow Alliance under the former vice-president, Mwai Kibaki.

With that victory, many Kenyans celebrated the end of KANU, the party that had come to symbolise oppression and all things bad in the country. In fact, many opined that KANU was dead and buried. A global opinion poll just after the Alliance came to power in early 2003 rated Kenyans as the happiest people on earth, the first time that honour, which normally goes to the Nordic countries, was bestowed on a third world country and African at that.

A supporter of Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi during an election meeting of the ruling Kenyan African National Union (KANU) in December 1992. Photo: Alexander Joe/AFP

Fast forward to the present and the younger Kenyatta is serving his second and last term in office after succeeding Mwai Kibaki in 2013 under the Jubilee Party, and a slew of candidates are angling to succeed him.

Leading the pack are long-time opposition leader Raila Odinga, who at one time served as KANU’s secretary general; the deputy president William Ruto, who for a long time served as a minister in the KANU government; as well as its secretary general, former foreign affairs minister and KANU organising secretary Kalonzo Musyoka; long–time minister in the KANU government Musalia Mudavadi; and Moi’s last-born son, Gideon Moi, who has since revamped KANU and which he now heads.

Back to 2002, and the ousting of KANU was a big deal in the country. In a paper titled ‘A New Dawn? Optimism in Kenya After Transition’, published as part of a series on Africa under the AfroBarometer in March 2004, authors Tom Wolf, Carolyn Logan and Jeremiah Owti said: “Eight months after the new government took office, interviewers took to the field to conduct the country’s first Afrobarometer survey. Overall, the survey findings clearly capture the palpable sense of almost unbounded optimism and hope that permeated Kenya in the days and months following the election.

“On item after item, Kenyans give some of the most positive assessments of their government’s performance, the quality of their democracy, and even the condition of the national economy, of any of the countries included in the Afrobarometer so far. They also stand out as having one of the highest levels of commitment to democracy and democratic institutions, and their confidence in a more bountiful future is overwhelming.”

In fact, Kenyans were replacing words with action. Just after the KANU defeat at the 2002 polls and into 2003, reports of ordinary people engaging in citizen arrests against policemen soliciting and receiving bribes were commonplace.

Prior to 2002, KANU had come to symbolise what a ruling party should not be. Year after year, Kenya made it into the top ranks of Transparency International’s Corruption Index. In 2001, for example, Kenya was rated two on a score of 10 (10 being the least corrupt), alongside Azerbaijan, Bolivia, Cameroon, Indonesia, Nigeria, Uganda and Bangladesh.

In his autobiography Memoirs of a Kenyan Spymaster, published in 2016, former deputy head of Kenya’s intelligence, Bart Kibati, details how well-connected people in the Moi administration grabbed and converted into public land and other amenities into private property, becoming obscenely rich in the process.

With the party under de facto one–party rule, the clamour for more democratic space gathered pace, with the then vice-president, Mwai Kibaki, telling off dissidents, famously prophesying in the late 1980s that “KANU would rule for 100 years”.

However, it was the assassination of long-serving foreign affairs minister Robert Ouko in February 1990 that kicked off serious agitation for multi-partyism in Kenya. Ouko, a suave diplomat who had the ears of world political powers, was seen by some in KANU as harbouring ambitions to remove Moi from power.

The chief government pathologist at the time, the late Dr Jason Kaviti, infamously deduced that the minister committed suicide by breaking bones in his legs, dousing himself with diesel, setting himself ablaze and shooting himself in the head. In a newspaper interview a decade later, Kaviti persisted in defending his outrageous theory.

In the first multi-party elections of 1992, Moi defeated the opposition, a feat he repeated in 1997, amidst claims of massive rigging. It was after this that Raila, the son of Kenya’s first vice president, Oginga Odinga, dissolved his National Development Party and joined KANU, becoming the ruling party’s secretary general.

Former Kenyan president and leader of the ruling Kenyan African National Union (KANU) Daniel Arap Moi inspects a guard of honour at the opening of parliament in March 1992. Photo: Alexander Joe/AFP

Raila had hopes of being anointed as Moi’s successor, since the constitution barred the president for running for a third term. But Moi went ahead to pick Jomo Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru, as his chosen heir. A broken-hearted Raila then made a noisy exit from KANU, taking several high-ranking officials with him. He teamed up with Kibaki under the National Rainbow Alliance Coalition to give the younger Kenyatta a hiding in the 2002 polls.

But now, the clock has come full circle, and as Kenyans head to the polls in 2022, it is former KANU leaders who are battling it out again, and so far, Ruto and Raila seem to be frontrunners in the race to succeed Uhuru.

So, what has changed and why? In 1988, Anthony Njui Nuguna, now 61, was elected as a councillor on a KANU ticket. He says the reason is that voter demographics have changed.

“A big number of people who are going to vote were either born in 2002 when KANU was defeated, or they were very young. Telling them about the excesses of KANU does not hold any water because they never saw it. To these people, such stories sound more like fairy tales,” says Njuguna who is readying himself to vie again in 2022, but definitely not on a KANU ticket.

Political analyst Gordon Opiyo points out, however, that while KANU helped shape the political and economic landscape of Kenya, right now the party is a pale shadow of its former self under the current leader, Gideon Moi.

But another analyst, Eric Baite, commenting on the re-emergence of former KANU leaders, says that in Kenyan politics, the more things change, the more they remain the same. “Moi was so omnipresent when he was in power for 24 years that TV or radio news bulletin always mentioned him as the first item. He then lived 18 more years after office – so it is difficult for me to imagine he is dead.

But another analyst, Eric Baite, commenting on the re-emergence of former KANU leaders, says that in Kenyan politics, the more things change, the more they remain the same. “Moi was so omnipresent when he was in power for 24 years that TV or radio news bulletin always mentioned him as the first item. He then lived 18 more years after office – so it is difficult for me to imagine he is dead.

“Independent Kenya will be 60 years old in two years’ time. If it was a person, it would retire from public service in 2023. However, it seems KANU isn’t done ruling Kenya. The founders of KANU ruled the country for 50 years; their sons have now taken over.”

Elections in Kenya, just as anywhere else in the world, are an expensive affair. To foot the huge bill expected of campaigns, presidential contenders will have to dig deeper into their pockets and reach out to the monied oligarchs who control politics via their wealth.

In Kenya, it is well known that the who’s who of the country’s business world made their money thanks to connections they had with KANU, either during Jomo Kenyatta or Moi’s administration.

In an interview with this writer several years ago, the Reverend Timothy Njoya, a respected clergyman and one of the activists at the forefront of fighting for multi-party politics in Kenya, said: “Look at the leading wealthy families in Kenya and you will see that they are either people who served in senior positions in government or did business with the government.”

Like Mafia dons sending their collectors to recall old favours, those now angling for the presidency will without fail call on these moneymen to chip in for campaign funds, a debt they will readily pay knowing that it is an investment for future government tenders and appointments to plum state jobs.

KANU, in one way or another, will indeed rule for 100 years as Kibaki predicted.

Tom Mboya is a Kenyan journalist working with an INGO in Nairobi. He was the 2009 Joel Belz International Media Fellow and the 2017 Coaching and Leadership Fellow, which is a programme offered by The Media Project and the Poynter Institute. His works have been published around the world.