At first glance, the term “inclusive governance” can appear nebulous, especially when compared to some of the more traditional concerns businesses and investors have. However, the principle which underpins the concept of inclusive governance, namely, that a more participatory, accountable and non-discriminatory governance process enhances economic development, has important implications for the private sector. These considerations are particularly relevant in a continent which has historically been characterised by divisions along economic, ethnic, generational, gender, regional and religious lines.

Inclusive governance helps development

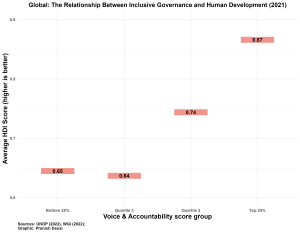

Good Governance Africa’s latest Intelligence Report focuses on drawing out the links between inclusive governance and broad-based economic development. By examining patterns at the global, continental, and African regional levels, we find that countries which support rather than supress participation are also more likely to score better on measures of broad-based economic development.

A key explanation for this is that a long-term governance environment which embraces accountability and participation across demographic groups is more politically stable than its unaccountable counterparts. In turn, this stable environment facilitates a consistent policymaking process which is required to sustain economic dynamism and meet citizens’ needs. To the contrary, governments that are not open to scrutiny make strategic mistakes, repress citizens and corrupt key accountability institutions, and therefore undermine sustainable development.

Our report considers the example of Angola where government actions in recent years have sought to repress rather than facilitate citizen participation. This has been one contributing factor to the recent stagnation and reversals which Angola has experienced in critical dimensions of economic development. Nonetheless, the ruling party’s electoral performance decline in the 2022 elections is a positive indication of the potential for greater citizen participation in the near future. Angola has also proved overly dependent on oil export revenue, which renders its coffers depleted when global oil prices fall. Oil rents also enable repression, which again indicates that private-sector oil players have an interest in strengthening institutions which will build citizen strength.

Operationally we used the Voice & Accountability (VA) measure from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators as a proxy for inclusive governance, and the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Index (HDI) to gauge broad-based development. The former considers the degree to which citizens perceive their country to possess critical freedoms such as expression, association and an independent media environment. The HDI encompasses several components of economic development including the traditional income per capita measure, as well as outcomes in health and education.

We find that the correlation between VA and the HDI holds over both shorter and longer periods of time, suggesting that the two reinforce each other. The patterns we observed are congruent with the robust academic literature which posits a positive relationship between democratic consolidation and long-run economic development.

The risks of suppression

Both our intelligence report and the scholarly research imply that the private sector has much to gain from bolstering democratically accountable institutions. The absence of these institutions impedes overall development and undermines the very political stability on which businesses typically thrive. It can also compel firms to engage in behaviour which either incurs significant financial costs, or places them at risk of long-term reputational damage, or both.

Recent actions taken by companies within Southern Africa illustrate this point in stark terms. Following attacks by insurgency fighters in Cabo Delgado province, Mozambique, petroleum giant TotalEnergies opted to employ private militia to secure its investments. This is standard behaviour for firms which see themselves merely as ‘policy takers’ and resource extractors who have no role to play in forging the institutional scaffolding of their operating environment.

Rwandan policemen guard The Total Mozambique LNG Project in Afungi in the Cabo Delgado province, Mozambique, on September 29, 2022. Photo Camille LAFFONT/AFP

Similarly, even responsible mining firms often avoid trying to persuade governments to pursue good governance, choosing to accept the status quo instead or simply choosing not to invest at all. This creates the space for irresponsible firms to enter the market and acquire licenses unscrupulously or entices firms like Bain to succumb to temptations that abounded during South Africa’s ‘state capture’ era.

The private sector’s role

What, then, can businesses do when faced with the many challenges they face while operating in Southern African countries and localities? Our intelligence report includes several recommendations in this regard, but it is worth reflecting here on a few key elements of what a prudent approach looks like.

The first component of an effective strategy necessarily requires companies to extend their horizons beyond traditional corporate social responsibility exercises as they seek to proactively build strong, mutually beneficial relationships with African governments, local communities and civil society organisations.

Investing in governance capacity building and strengthening existing democratic accountability mechanisms is a core part of this. Given the nature of their work, companies should commit to transparent operating practices. This is primarily applicable when a company is pursuing contracts with, or attempting to attain licenses from, a government. By making their own participation contingent on a transparent and fair bidding process, companies are financially incentivising accountable conduct from governments.

Moreover, through advocating for the drafting of strong anti-corruption policies, firms can help reduce the ability for host governments to engage in deceptive rent-seeking behaviour. Committing to these policies would also help protect the private sector from the reputational damage which bribe paying invariably produces.

Finally, businesses have an important role to play in encouraging citizens to partake in holding their governments accountable. Practical steps would involve companies helping finance training workshops and holding advocacy engagements on pertinent matters. This can uphold key inclusive governance principles if companies make their support for these events conditional on hosts committing to encourage citizen participation from all demographic groups present in a country.

Through investing in these initiatives, businesses can help make inclusive governance a reality within many African countries. The positive effect which a more accountable and participatory governance process has for economic development is clear. Equally apparent is that this approach will help the private sector simultaneously reduce its above-ground risk and improve their triple bottom-line.

- A version of this article also appears in Business Day