“Young, dumb, broke, high school kids.” These lyrics from a contemporary pop song often heard on repeat do not exactly inspire confidence. On the contrary, Africa’s youth, while they are obviously young, are bright and “woke”, to use another trending word. That is, they are highly aware of the social world around them and conscious of the injustices that prevail. Sadly, however, many of our continent’s children will neither make it to high school nor complete their secondary education, through no fault of their own. So is this cause to lie down, curl up and resign ourselves to a fait accompli?

“Young, dumb, broke, high school kids.” These lyrics from a contemporary pop song often heard on repeat do not exactly inspire confidence. On the contrary, Africa’s youth, while they are obviously young, are bright and “woke”, to use another trending word. That is, they are highly aware of the social world around them and conscious of the injustices that prevail. Sadly, however, many of our continent’s children will neither make it to high school nor complete their secondary education, through no fault of their own. So is this cause to lie down, curl up and resign ourselves to a fait accompli?

When I recently asked several young people at the African Transformation Forum in Accra, Ghana what they regarded as their biggest challenge and as their biggest opportunity, many of their answers came as little surprise. A young gentleman responded “job opportunities” and “education” respectively, while the first young woman suggested “health” and “self-advancement”. Another youth mentioned “sustained self-sufficiency” and the “innovative use of existing resources”. These voices confirm that African youth are aware, creative, highly adaptive, resilient and responsive to the life challenges facing them. Far from a dejected pessimism, there is an open attempt to engage reality.

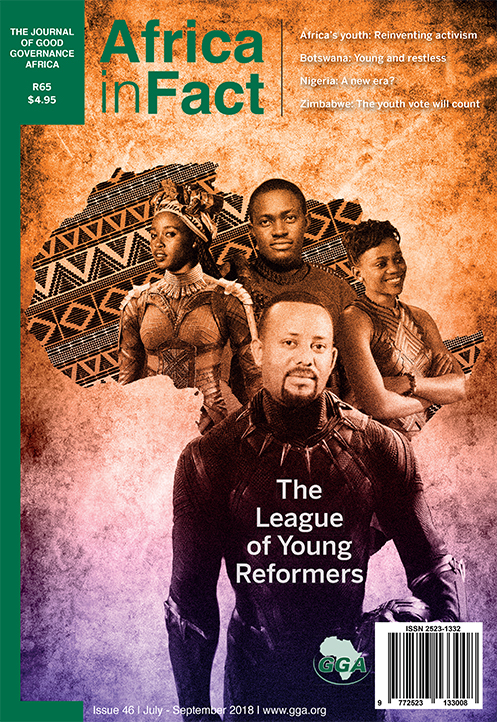

Much like our upbeat cover, adapted and used with permission, the box-office hit Black Panther provides an apt portrayal of what might transpire should a fantasy world become real. In one of the chapters of the above forum – Youth Employment and Skills (YES) – we have been sharing animated debates on what practical policy developments might entail to make the aspirations of young Africans for a better life real. Like the main figure and heroes of Wakanda, key decisions revolve around leadership and choice. And it isn’t just leaders but the youth themselves who often act as superheroes, albeit unrecognised and often in disguise.

Dilemmas confronting our young people are like moving targets: the changing nature of work, labour supply and market demand, the fourth industrial revolution and a commensurate boom in new media and ICT services. The goodness-of-fit between an imposed, traditional (dare we say colonial?) textbook education system and the urgent need for dynamic TVET (Technical Vocational Education and Training) skills must be questioned, along with cultural taboos around opting for trades and enterprise over professions.

So the reality is that the profile of our African young person looks a bit like this: I am rejecting the old elite and am increasingly active in non-partisan, grassroots politics. I may live in poverty with little or no access to quality education, but I have embraced technology. While I face numerous barriers to entry to the job market, with sparse opportunities for formal employment, I am creating non-traditional jobs. I am greatly exposed to poor nutrition and communicable disease, such as HIV, but I have little access to healthcare and a wellbeing safety net. I may be fodder for criminal syndicates, extremist groups, exploitation and trafficking, yet I retain a sense of dignity and purpose and actively innovate to chart my own course. I am an African youth.

As always with Africa in Fact, the contributors to our current edition have not shied away from the stark reality facing us. Rather than to promote a gloomy outlook, the stories, positively grappled with, serve to make us, the readers, sit up and think and approach this challenging topic from different angles, mindful of history and context. We have the voices of the youth themselves, and a commensurate critique of being referred to as a dividend or a “bulge”. Besides this, we carry our trademark blend of hard news, journalistic content and academic/practitioner analysis. Instead of providing a synopsis, we have chosen to let the stories speak for themselves.

One story that does deserve mention is our own Child Development and Youth Formation programme. As the pilot roll-out features within the journal, we shan’t dwell on that here. Suffice it to say that children and youth have been identified as a key pillar of our work at Good Governance Africa (GGA), as they are unequivocally the future of our continent and of our world. Unlike a certain (non-African) administration that has taken to locking up children separated from their families, we strive to support the view of an enabling and nourishing environment; of an ecosystem that is holistic and wholesome and within which each child is located relative to their family, carers and educators, community leaders and broader societal figures.

In our preferred scenario, government at various levels affords the optimal development of the person across their lifespan, actively collaborating with the private sector and civil society. We have started young, at pre-birth, in fact. We sponsor the training of women, who represent marginalised deep rural and peri-urban communities, as internationally accredited ECD teachers with the Indaba Montessori Institute. We are engaging children, teachers, parents, and the broader community to promote inclusive participation, and in some instances we are physically redesigning schools. Our hope is that, with the support of key stakeholders and committed partners, we can extend from children aged 0-3 through to age 12 and move to scale in the years ahead.

So, with youthful enthusiasm, let us affirm that we are never too young to run!

ALAIN TSCHUDIN is a former Executive Director of Good Governance Africa. He is a registered psychologist with Ph.D.s in Psychology and in Ethics. He was a Swiss Academy Post-doctoral Fellow at Cambridge and oversaw the Conflict Transformation & Peace Studies Programme at UKZN for several years. He has broad research and community engagement interests and has worked for various universities in Africa and Europe, with the European Commission, with local and international NGOs, as CEO of a leadership development agency, and as lead consultant for Save the Children and UNICEF, most recently as Child Protection Assessment Coordinator for Northern Syria. Alain has an adjunct association with the International Centre of Non-violence (ICON) and the Peacebuilding Programme at the Durban University of Technology.