The Zimbabwe Constitution guarantees social protection, but provision and accessibility are hampered by fiscal limitations

Zimbabwe, Monzou Village (one hours drive from Harare., 17 November 2017. Monzou villagers. The poor small scale farmers’ dwellings and crops have been destroyed several times as Grace Mugabe attempts to evict the community from the land and annex the land to her neighbouring farm.

In contemporary African countries social protection is broadly perceived as central and indispensable to human development. Persistent and chronic forms of poverty that often find expression in people’s failure to access life’s basic necessities, such as nutrition, health and education, have focused attention on social protection as a human and socio-economic right.

The discourse on social protection has gained impetus in Zimbabwe, particularly in the past two decades, due to economic decline and social malaise, which has accentuated levels of vulnerability and severely curtailed people’s capacities, individually and collectively, to cope with shocks, risks and contingencies.

This article discusses the ways through which different forms of social protection or social security are recognised in Zimbabwe’s Constitution and how these provisions find expression in the everyday lives of individuals. I look at some of the factors that have impeded the realisation of the constitutional provisions and the consequences that a failure to fulfil constitutional entitlements has for individuals and communities.

Drawing from Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler’s working paper Transformative Social Protection (2004), social protection is defined as: “All public and private initiatives that provide income or consumption transfers to the poor, protect the vulnerable against livelihood risks, and enhance the social status and rights of the marginalised; with the overall objective of reducing the economic and social vulnerability of poor, vulnerable and marginalised groups.”

The provision of forms of social protection to individuals and households is highly contested. On the one hand, there is a belief that social protection programmes put a massive strain on state finances and create a dependency syndrome among the recipients (see for example Devereux and White 2010; and Makhema, 2009). On the other hand, proponents and advocates of social protection programmes argue that such programmes tackle transitory and chronic forms of poverty and lack, and enhance people’s livelihood capabilities and improve their access to basic necessities (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, 2007). In a sense, social protections fulfil people’s human rights by helping them escape the consequences of poverty.

Zimbabwe has, for the past two decades, been confronted by a complex and intertwined political, economic and social crisis that has resulted in massive job losses in the formal economy and the growth of a “survivalist” informal economy.

Apart from high unemployment in urban areas, households’ risk-management strategies and capabilities, especially in the rural areas, have been curtailed by variable weather and climate conditions that have resulted in reduced agricultural productivity, food insecurity and low incomes, which in many ways worsen hardships.

The new Constitution of Zimbabwe takes the progressive view that the provision of social protection advances the fulfilment of human rights. As such, constitutional provisions reinforce this view and advance the human rights agenda.

Chapter two, section 30 of the Constitution states that: “The state must take all practical measures, within the limits of the resources available to it, to provide social security and social care to those who are in need” (Government of Zimbabwe, 2013).

The provision is aligned with article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which stipulates that everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care and necessary social services rights (see Masuka, 2014).

There are three main forms of social protection in Zimbabwe; social insurance, social assistance and social allowance. Social assistance comes in the form of non-contributory schemes funded from public resources, and in Zimbabwe this includes the Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM), the Harmonised Social Cash Transfer Programme, the Drought Mitigation Programme, as well as the Grain Loan Scheme, among other forms provided to indigent individuals.

Social insurance schemes are in the form of contributory schemes managed either by the state or private-sector actors. They include retirement pensions and grants, invalidity pension and grants, medical aid schemes and survivors’ pension and grants.

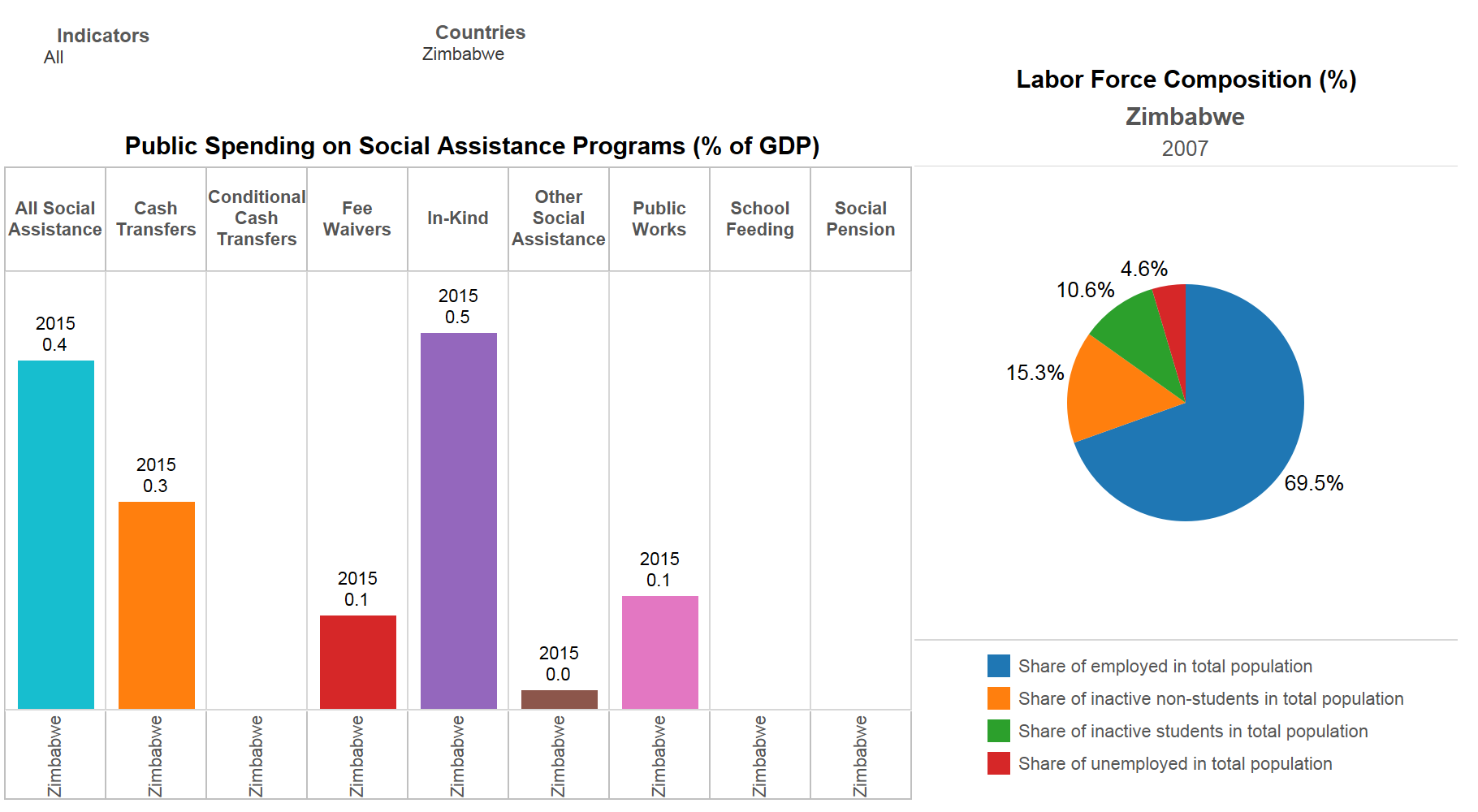

Source: World Bank

Historically, social-protection strategies have taken various forms from the Social Dimension of Adjustment (SDA), whose main programme was the Social Development Fund, introduced to address the vulnerabilities that came as a consequence of neo-liberal economic austerity measures in the 1990s.

Some of the successive programmes include the National Action Plan for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (NAP for OVC), which reached 241,664 orphans and vulnerable children with different forms of assistance (Department of Social Welfare, 2010).

A recent programme developed as an offshoot of the OVC programme is the Harmonised Social Cash Transfers programme introduced in 2011-2015 to support vulnerable groups such as child-headed households, the elderly and the disabled.

The recognition of social protection as a right within the Zimbabwean Constitution is an important milestone towards securing people’s human rights and ultimately realising Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, some of the social protection schemes fail to meet certain key attributes of effective social protection such as predictability, consistency, transparency and sustainability.

In the first instance, a significant limitation is that the Constitution places a caveat on the provision of social protection. The Constitution stipulates that: “provision of social protection should be provided within the limits of the resources at the disposal of the sitting government (own emphasis)”.

In a context of constrained or limited government funding, which has characterised the past two decades, the provision of these constitutionally guaranteed rights falls into the danger of becoming a mirage. Presently, the Zimbabwean government is saddled with billions of dollars in internal and external debt, with 90% of its revenue being spent on the civil service.

In such a constrained fiscal context, very little money is available for social services, including different forms of social protection, exacerbating levels of vulnerability (see the Transitional Stabilisation Programme 2018).

The other problem that impedes the realisation of social protection rights is their inaccessibility. There are bureaucratic bottlenecks involved in trying to access these schemes. Potential beneficiaries have to pass a tough means testing process, which in some instances may exclude deserving clients.

Some of the prospective recipients have to travel long distances to apply for assistance, and given the relatively low benefits there is little incentive for them to do so. The result is the possibility of applicants incurring more expense than the assistance they seek from the state.

Most of the applicants are also the elderly and the disabled, who are unlikely to be able to withstand the rigours of visiting government offices for the application process. The Harmonised Social Cash Transfer programme, however, attempts to promote accessibility and participation in that it is conducted at community level.

In conclusion, from a rights-based perspective, there is general consensus that social protection schemes enhance livelihood capabilities and in many ways meet individuals’ access to basic necessities. By doing so, the different social protection schemes tackle pervasive inequalities in a context of limited livelihood resources characterised by different forms of hardship.

However, the provision of social protection is hampered by fiscal limitations and, although there are constitutional guarantees providing for social protection, the actual provision is determined and limited to the resources available to the government.

In addition, there are also technical challenges that curtail access to forms of social protection, and in many ways these accentuate rather than alleviate the plight of vulnerable groups such as the elderly and the disabled.

REASON BEREMAURO holds a PhD in anthropology from the University of the Witwatersrand where he was affiliated to the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER). Dr. Beremauro is a lecturer at the Midlands State University (MSU). His research interests are in migration, the anthropology of humanitarianism, social protection and victimhood.