Daily life in Bamako, capital of Mali, on 5 February 2022. ECOWAS placed sanctions on Mali as a result of the junta administration’s decision to postpone democratic elections in Mali for five years, which had a detrimental impact on the economy. Photo: Nacer Talel/Anadolu Agency via AFP

The wave of coups and military takeovers that has swept through West Africa over the last 24 months calls into question the ability of both the African Union (AU) and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to uphold democratic principles and maintain peace in the region. Continental and regional organisations can and should serve to instil among member states the kind of governance norms and practices which deter unconstitutional changes of power and other major violations of constitutionalism and the rule of law. We take a critical look at responses by the AU and ECOWAS to these events in order to determine reasons why both bodies have seemingly failed in this regard, and where improvements could be made.

AU democratic norms

The AU has a mandate to promote democracy and good governance on the African continent, and in doing so, has developed several policies and normative frameworks which address coups and other unconstitutional changes of government both directly and indirectly. Most notably, the 2000 Lomé Declaration for an OAU Response to Unconstitutional Changes of Government, and the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, both identify coups as a major threat to peace and security on the continent and identifies actions to be taken against perpetrators and countries that support perpetrators.

However, the adoption and implementation of these policies at the national level has remained a perennial challenge for the AU. For example, the African Charter, which was adopted in 2007 and came into force in 2012 and is the primary normative instrument for setting governance standards on the continent, has only been ratified by 30 member states to date.

Serious and longstanding governance deficits have been a significant factor in the recent wave of military takeovers seen across West Africa. However, the AU has not taken a proactive approach to addressing these underlying issues. Doing so may have served to improve political stability and contribute to the peace and security. Although the AU has not been entirely silent, there is a broad agreement among scholars that the AU has not effectively pursued its goal of peace and security on the continent.

Challenges facing AU responses

The absence of a shared set of common values on key governance principles among member states remains a significant challenge for the AU. One reason for this is that unlike other regional organisations, such as the European Union (EU) which sets certain democratic criteria, the only criteria for joining the AU is that the applicant be an African state. As a result, the AU has not always taken a collective and unified response to coups and other unconstitutional changes of power. An example is the issue of a non-retroactive two-term limit rule, which can cause division, as seen during the ECOWAS summit in 2015 in which Togo and Gambia resistance the intention. PSC member states often differ on decisions based on several factors, including cultural and political values.

As with other large continental and regional bodies, the AU has succumbed to the irresistible pressure of realpolitik, and needs to balance its practical objective of resolving security challenges and normative objectives, such as promoting democracy and human rights. A case in point is the Mali and Chad coups, where many saw the justification of the Chad coup and the condemnation of the Mali coup as an example of leaders speaking on both ends of their mouth. Chad has a major, effective army in West and Central Africa, and surrounding states rely on it for security. This may well have influenced the stance the AU took on the Chad coup. Such instances start to gradually erode the compliance of the AU’s legal and political frameworks, giving way to personal preferences rather than maintaining the legal framework with consistency.

In some instances, the AU has been seen as prioritising power over justice due to its marred structure. On numerous occasions, unpopular leaders have found themselves in positions of power within the AU, regardless of the accusations and atrocities they are facing at home. An example is the appointment of Mali’s Ibrahim Keita as the champion of Arts, Culture and Heritage within the AU, while facing a public outcry for security reforms. Ibrahim was ousted the next year in a coup. These appointments undermine the credibility of the AU and give additional powers to authoritarian leaders as most offenders are exempt from vocal criticism by the AU.

Despite the AU’s mandate to “coordinate and harmonise” policies between the continent’s regional organisations, none of the primary documents of regional organisations, including ECOWAS, refer directly to the importance of the AU. Instead, most major security concerns are increasingly becoming the responsibility of regional organisations, and they seem to be at the forefront of dealing with peace and security issues. This puts a great deal of pressure on these regional organisations to succeed in dealing with security threats, and if they fail, it isn’t clear whether the AU should step in to assist.

ECOWAS – the vital signs of democracy in the region

On 3 February 2022, Heads of State convened at an Extraordinary Summit of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to discuss the political and security developments in Burkina Faso, Guinea and Mali. The regional body condemned the recent attempted coup d’état in Guinea-Bissau and coup d’état in Burkina Faso, which occurred within just two weeks of one another.

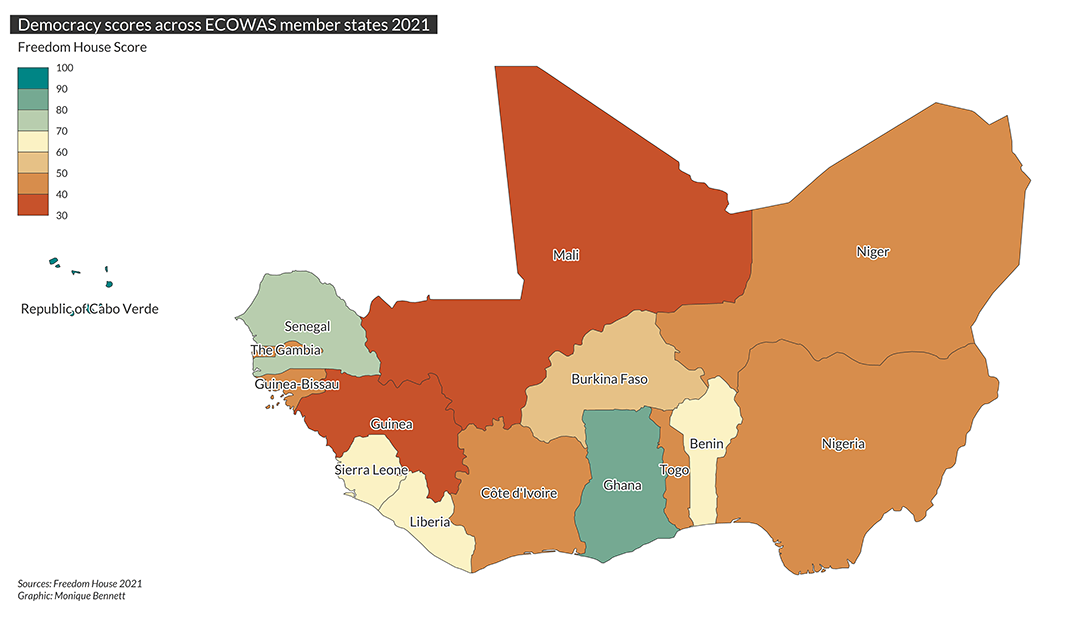

Despite the regional body having an established framework for the protection of democracy and freedom, the recent political breakdowns indicate an inability to agree on the foundations of democratic and inclusive governance among its member states. Moreover, the democratic identity of almost all ECOWAS members, besides Cabo Verde and Ghana, are either “not free” or “partially free”, according to the latest Freedom in the World report (see map below). The democratic homogeneity of ECOWAS members is important to consider when examining the regional organisation’s ability to uphold democratic norms and prescribe effective responses if there is a breakdown of these norms. Several of the regimes across the Sahel are fragile democracies where the military is closely intertwined with politics. These regimes are particularly vulnerable to unconstitutional changes in leadership, as they create a power vacuum between the breakdown of leadership and the constitutional election of new leaders. There is also a lack of institutional oversight that would usually be in place to prevent unconstitutional changes in power.

The map below provides an overview of the strength of democracy across ECOWAS member states according to Freedom House. Burkina Faso, Mali and Guinea scored 54, 38 and 33 (out of 100) respectively, which falls below the average across the member states.

What is ECOWAS and why was it formed?

The origins of ECOWAS stem from the region’s initial efforts to economically unify its francophone states via a single currency union, the Communauté Financière Africaine (CFA). Later, in 1965, an agreement for increased economic cooperation emerged. Finally, former Nigerian Head of State Gen Yakubu Gowon and his Togolese counterpart Gnassingbe Eyadema drafted the basis for what became the Treaty of Lagos in 1975. Over the next two decades, the scope of ECOWAS’ mandate has broadened as a consequence of the political and security challenges facing its members.

During the 1990s, crises in Liberia and Sierra Leone spotlighted the security dilemmas facing the region and saw the organisation pursue an institutionalisation of democratic norms and values through several frameworks, the latest being the ambitious 2001 Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance. This protocol contains 12 constitutional principles that all members must formally subscribe to, including what experts describe as the “separation of powers, legitimate means for acceding to power and appropriate civil-military relations”. Furthermore, the protocol provides modalities for implementing sanctions in terms of Article 45(1), stating that if democracy is “abruptly brought to an end by any means or where there is massive violation of Human Rights in a member state, ECOWAS may impose sanctions on the State concerned”.

Unpacking the peace and security mandate of ECOWAS

The provisions of the 2001 protocol were expected to be internalised by member states, acting as the building blocks for institutionalising liberal peace and democratic values. Unfortunately, the regional political landscape has long been characterised by unstable and authoritarian regimes. An illiberal electoral environment across the member states created a political landscape which assumed the only way to enact reasonable change would be through undemocratic and often violent means. Addressing these regional security threats falls under the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security (1999), which is primarily governed by the Mediation and Security Council (MSC). The MSC decides on all matters relating to peace and security issues on behalf of the Authority of Heads of State and Government, the highest decision-making body of ECOWAS.

Early on the organisation emphasised the importance of resolving intra-state and inter-state conflicts through mediation and other diplomatic tools under the 1999 Mechanism. Early attempts at intervention and peace settlements, as in military coups and civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2002) and Guinea-Bissau (1998-1999), failed due to the inability of the organisation to formulate sustainable peace agreements as well as maintain an effective peacekeeping military presence in both scenarios. The military coups in Sierra Leone and Guinea-Bissau were significant tests for the mediation and intervention efforts of ECOWAS, forcing the organisation to evolve and have their efforts complemented by the AU and United Nations (UN).

ECOWAS response to coups

Despite the difficulties facing ECOWAS in ensuring member states comply with the broader framework of democracy and good governance, the organisation has remained consistent in its public response to coups d’états across the region. The organisation, however, is limited in its ability to respond to unconstitutional changes in leadership.

Sanctions and suspensions have been the regional body’s main tactic in response to coups, but recently they have failed to deter opportunistic military actors from using coup d’états to gain political power. ECOWAS should consider whether their sanctions regime is having the desired effect. The recent sanctions placed on Mali have a stronger impact on the general population than on those implicated in the coup. Targeted sanctions towards individuals may be a better option to maximise their effect. However, the authority structure of ECOWAS makes this kind of intervention difficult. Patrimonialism arguably not only exists within some West African states, but also exists within ECOWAS. Neutrality within the highest authority structure, the Heads of State, does not exist. Therefore, decisions made within this structure will carry bias and therefore be ineffective in dealing with breakdowns of democratic rule.

Calling for a clear timeline on elections has been another main feature of the organisation’s strategy for finding and maintaining stable governance but in most cases, this has not been a successful and stable solution. An inclusive mediation and peace process strategy before elections may help iron out grievances between both the military and civilian actors, so elections can proceed in a more stable political environment.

Tenure elongations are another critical issue facing ECOWAS. Incumbent presidents seek to extend their rule beyond the constitutional mandated two term limit. In the case of Guinea, we see the consequences of President Lansana Conte’s tenure extension in the form of a coup, which could also be seen as a rebellion against the former President’s unconstitutional actions. In Burkina Faso, the coup was, in part, a result of the government’s failure to adequately support the military’s efforts against the insurgency boarding Niger and Mali, which has already displaced 1.5 million people. Constructive criticism towards regime leadership by the relevant ECOWAS authority should be part of the organisation’s diplomatic strategy, otherwise new leadership will repeat the same mistakes as before.

Way forward

The AU and ECOWAS have been faithful in their frameworks by imposing sanctions and suspending member states. However, it is clear that the measures taken by these organisations have not been adequate in deterring coups. Efforts to create a security regime have been constrained and undermined by a lack of shared values, regional allies and the legitimisation of despotic leaders. Moving forward, the AU should focus on playing a more proactive role alongside regionalisation organisations like ECOWAS. Increased awareness on the security difficulties facing its members could pre-empt potential democratic breakdowns. Accountability mechanisms should be developed to ensure member states internalise and uphold the governance norms set by both the AU and ECOWAS. Effective regional cooperation is essential for the region to achieve peace, security and stability that will ultimately encourage economic and social development.

[activecampaign form=1]