The landscape of foreign aid in Africa has shifted from being strategically western dominated, specifically by the United States, to China, emerging as one of the leading countries providing aid to the continent, especially in technology infrastructure.

Chinese foreign expenditures in Africa shot up from $631 million in 2003 to $3 billion in 2015, while US spending in Africa has decreased. Many western donors have taken a back seat in developmental assistance for technological infrastructure in Africa, and China is building a solid presence on the continent through its various programmes aimed at technological infrastructure. Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Digital Silk Road (DSR), China is cementing its position as a partner of choice in foreign assistance for African countries in the 21st century.

A 1973 archive image of Zambian prime minister Kenneth Kaunda and Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere visiting a tunnel constructed by a Chinese team, in Uhuru, Tanzania. Photo: AFP

What does this mean for the US? To understand the meaning and implications of China’s expansion in terms of digital technology in Africa, it is essential to first give context to the nature of Chinese foreign aid on the continent and its rise.

Contrary to popular belief, China is not a newcomer in African developmental aid. China began providing African countries with foreign assistance after the 1955 Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia. This initiative was backed by the Chinese government’s eight economic principles for foreign assistance. In the 1970s, China built the TAZARA railway line between Zambia and Tanzania with interest-free loans. During that time, China had more aid programmes in some African countries than the US. With Chinese economic liberalisation in the 1980s, its foreign aid to Africa continued to grow. Chinese foreign aid is a mixture of concessional loans, aid, and interest-free loans.

However, the Chinese government has created an opaque financing approach, which researcher Motolani Agbebi has explained as subsidised loans given to their clients, with the aim of Chinese government-backed firms receiving contracts for the projects through a closed-door bidding process.

Agbebi argues that these “DSR projects are primarily driven by government-to-government initiatives and backed by concessional lending agreements that favour Chinese contractors, which undoubtedly advantages Chinese firms”. Therefore, Chinese funding is not pure aid but a mixture of several foreign assistance methods with various returns for the Chinese government and firms. For example, Sierra Leone’s $30-million loan to finance its contract with Huawei for the second phase of its National Fibre-Optic Backbone Project was funded by Exim Bank of China. The agreement was between the Sierra Leone finance ministry and the bank’s representative, the political counsellor of the Chinese Embassy.

Passengers queue to ride Ethiopia’s new tramway in September 2015 in the capital Addis Ababa. Sub-Saharan Africa’s first modern tramway marked the completion of a massive Chinese-funded infrastructure project hailed as a major step in the country’s economic development. Photo: Mulugeta Ayene/AFP

In 2013 China launched the BRI, a flagship developmental programme consisting of different projects focused on domestic and international development. Paul Nantulya, a research associate at the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, asserts that the aim of BRI is “the building of a new global system of alternative economic, political, and security ‘interdependencies’ with China at the centre.” The BRI programme has grown since its inception in 2013 to include more than 146 countries worldwide, 46 of them African.

One of the fundamental initiatives of the BRI is the DSR. According to global digital economy expert Winston Ma the DSR seeks to make “infrastructure development more viable, efficient and sustainable in the long run” and “bring advanced IT infrastructure to the BRI countries, such as broadband networks.” It also seeks to create “e-commerce hubs and smart cities, [with] medium and small merchants connected to global trading via digital networks”, “harnessing and the application of big data to solve environmental challenges directly”, and “providing basic internet access”.

The DSR responds to Africa’s greatest need in the 21st century, filling the digital technology gap. China’s approach through the DSR fits strategically into providing for that need, and it is China filling the void. This void was created by the retreat of western donors in the sphere of infrastructure funding in Africa. The Director of the Development Co-operation Directorate of the OECD, Jon Lomøy, avers that the decrease in western aid in Africa was firstly caused by a greater emphasis on operation and maintenance costs, leaving many projects as white elephants.

Secondly, western donors started believing in financing African infrastructure development through private commercial investments. Lastly, assessments in project planning become costly and politically cumbersome as they involve various aspects of the recipient country, including “technology, economics, gender, environment, socio-cultural dimensions, corruption, risks for harassment to mention some”.

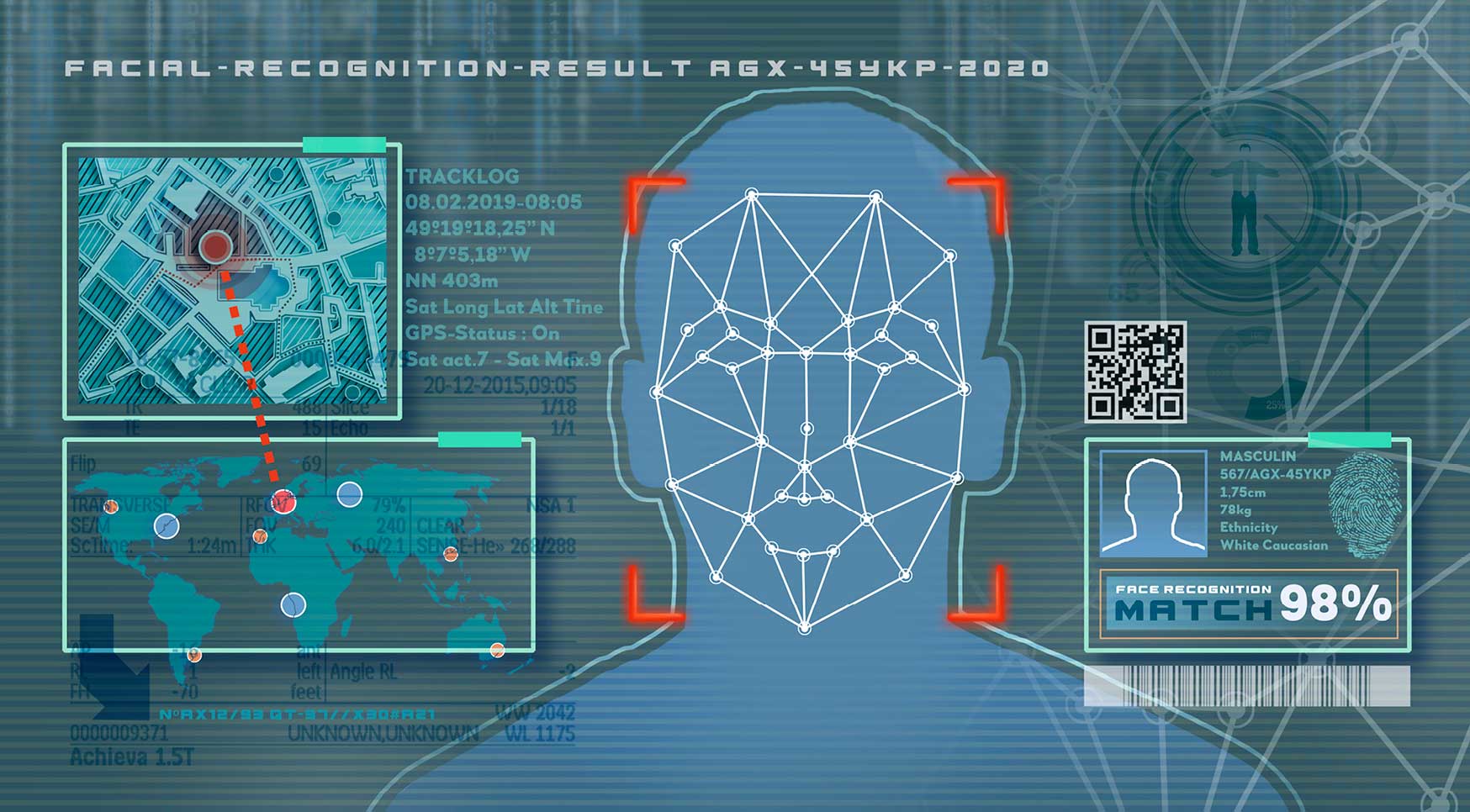

Chinese companies have entered contracts with the Zimbabwean government to provide surveillance and law enforcement facial recognition technology. Photo: Getty Images

The US approach toward foreign aid, which insists on promoting democracy and respecting human rights for recipient countries to receive funding, worsens the situation and opens the space for China, which does not require human rights assurances to provide funding for development purposes.

According to researcher Chaorong Wang, the US spends more on health and education while China spends more on infrastructure, specifically transportation, energy, and communication. Wang states that “US spending on the top three sectors receiving Chinese aid is only at 2.6%, 0.8%, and 0.07% of the total official development assistance (ODA) amount.”

As a global power, the US’s failure to extend its influence in Africa’s digital technology infrastructure development has dire implications and meaning for its foreign aid efforts (democracy and humanitarian) and foreign interests in Africa – and its position as a global power.

First, the US has positioned itself as a leading global power that fosters and supports democracy in Africa. As a result, most of its funding in Africa is spent on democracy-building initiatives. However, Africa’s solid Chinese digital footprint is undoing that work as most repressive African governments are now using digital systems to repress their citizens. For example, Chinese companies have entered contracts with the Zimbabwean government to provide surveillance and law enforcement facial recognition technology. This will potentially increase the Zimbabwean government’s human rights abuses. However, these issues are not in China’s foreign interests, though they are for the US, which is slowly losing power in Africa’s digital world.

Second, Chinese digital companies, including Huawei and ZTE, have been banned in the US due to allegations of spying. Equally, US companies like Google have indicated their intention to take Chinese gadgets off their platforms. However, this aggressive move by the US was not thought through, especially its impact on African companies, where Chinese digital infrastructure is widespread.

Instead of hindering Chinese digital footprint growth, this may embolden it and encourage African countries to embrace Chinese digital technology fully. Senior Policy Fellow at the Centre for Global Development Gyude Moore notes that the US did not offer African countries an alternative to counter Chinese digital infrastructure by banning Chinese technology. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa expressed concern about the US actions against Chinese firms, which he believed are “to deliver a comprehensive and what we believe to be an advanced solution in the telecommunications space.” In most African countries, the response to the US trade war with China has been met with the same concern.

Last, the 21st-century Cold War is being waged in the arena of digital diplomacy, and through its funding and provision of aid in Africa, China is getting the upper hand. However, there is hope for the US in its launch of the Build Back Better World (B3W) economic programme and its G7 partners. The initiative aims to mobilise finance for infrastructure programmes that involve technology for low- and middle-income countries. In addition, the initiative aims to counter the BRI. This competition is welcome as it may give African countries alternatives and spur them into their fourth industrial revolution – if the new technological age will still be the fourth industrial revolution.

[activecampaign form=1]

Prince Mudauis a lawyer with a keen interest in non-profit governance, international development and philanthropy.