The resource-rich Central African Republic faces major obstacles to development

The capital of the Central African Republic (CAR), Bangui—hardly a Paris in the jungle—one encounters a nation without even the rudimentary bones of nationhood. The countryside seems caught in a different era, totally cut off from anything resembling the 21st century. There is no sign of any industry, and the only machines belong to the French peacekeeping effort.

With an estimated population of 4.8m, according to the World Bank the landlocked nation was once a nexus of the continent where vast 200-person canoes powered down the Congo River’s tangled tributaries. Its present borders were defined by France, which made it a colony in the late 19th century. Independence came in the late 1950s, but having been subjected to slavery for centuries, and then, under colonial France, to forced labour practices, it is arguable that the people of CAR represented too small and demoralised a population for nationhood.

Barthélemy Boganda, the country’s liberator, wanted it to be part of a central African region: a proto-European Union that would offer strength in numbers. He warned of turmoil if an independent CAR was untethered from a larger federation of central African states. Reluctantly, Charles de Gaulle, then president of France, agreed, after he came to the conclusion that liberation for his colonial properties was inevitable. According to Pierre Kalck’s superb history of the region, “Central African Republic: A Failure in De-Colonisation”, central Africa was then carved up into fiefdoms, which served the French business elite. A contingent of Gabon colonials blocked federation in the late 1950s.

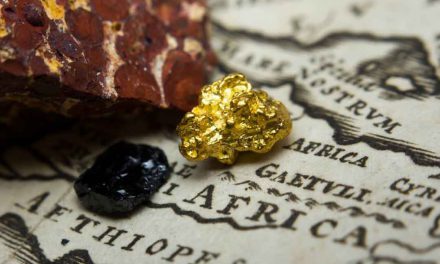

It is tempting to think of “before and after” French colonialism in CAR, but the distinction may be merely semantic. The French nuclear effort relied on Central African uranium; French businessmen shipped out Central African diamonds with impunity. Then, in the early 2000s oil was discovered in the sweltering northern region of Vakaga, which is believed to have huge reserves. Rights for oil exploration were granted to a US company and several Chinese ones, but then disputed, according to a study by IPIS, an Antwerp-based independent research organisation. The ongoing political conflict is believed to have prevented drilling.

The uranium mines no longer function, and the country’s diamond mining sector is one of the continent’s greatest scams—a smuggler’s paradise with no oversight and no regulation. All of this results in a gross national income per person that has dipped from $0.96 to $0.72 since 1980, according to the World Bank, representing one of the lowest on the planet.

The Séléka, an alliance of northern military rebel groups led by Michel Djotodia, emerged in 2012 and marched on the capital, claiming that the government had ignored the terms of an earlier peace accord, according to a 2015 report by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). According to the rebels themselves, the spectral presence of black gold—yet another manifestation of the “resource curse”—tipped the country into conflict.

The Séléka, a ”drastically more violent group” than its predecessors, according to ACLED, arrived in Bangui in March 2013. By then President François Bozizé, abandoned by the very people that had supported his own coup ten years earlier, had fled the country, leaving remnants of his Christian militias to form the Anti-Balaka, a predominantly Christian coalition of vigilante groups. Its stated aim was to defend communities against the Séléka, which has been widely accused of human rights abuses.

Mr Djotodia served as president briefly but he either could not, or did not want to, rein in the Séléka. Suddenly Muslims and Christians were murdering each other in the streets, and CAR found itself locked in the bloody civil war against which Mr Boganda had warned before his mysterious death in 1959.

The civil war, and the subsequent political wrangling, have resulted in a constant baseline of chaos. Elections have been constantly delayed, leaving the country without a functional government. What’s left is a husk of a country, and one of the most underdeveloped places on earth: CAR ranks at 180 out of 187 in the United Nations Development Index. In 2013, the total per-capita net inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) was $1.85m, according to the World Bank.

The country is estimated to have significant mineral deposits and other resources, including uranium, gold, diamonds, cobalt and timber, as well as “the potential to be a net agricultural exporter”, according to a recent US State Department report. But it is now the fifth-worst country in the world in which to do business, according to 2016 figures from the World Bank. The US State Department attributes this to number of factors, including poor infrastructure, an unskilled workforce, and rampant corruption.

In 2013, when war broke out, only $800,000 entered the country from abroad, as compared to the $71m that flowed in during 2012. This has left the treasury critically short of foreign exchange, which makes importing fuel and other necessities impossible. There are no roads or railways, and little funding to build much-needed infrastructure.

In 2001, hoping to attract international business development, Ange-Felix Patassé, Mr Bozizé’s predecessor, adopted the Central African Investment Charter. Co-signed by Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Chad, along with CAR, the charter was a common feature of the member states of the Central African Economic and Monetary Community.

The charter established a common tax and tariff policy, programmes suspending temporary admission taxes, as well as the removal of VAT from exported goods, the reduction of high fees for establishing new businesses and offering tax breaks to stimulate the training of locals. Companies investing $200,000 or more were offered a full tax break for three years, with full tax rates payable only by year seven. Companies investing in projects 300km or further from Bangui would earn three additional years of tax holiday.

Mr Bozizé’s regime also instituted IMF/World Bank economic restructuring programmes with a view to privatising state-owned enterprises and enticing investment. A new mining code was instituted in 2009, and the charter was updated in 2011, further liberalising the economy. But none of this stimulated FDI inflows.

“Corruption is a major obstacle to foreign direct investment in the Central African Republic,” the State Department report notes, “and…is pervasive in government procurement, dispute settlement and taxation.” Transparency International’s 2014 Corruption Perceptions Index ranked CAR 154th out of 175 countries.

Like most countries reliant on commodities, CAR’s economy took a beating during the 2008 financial collapse, and it is faring even worse during the current slowdown. There is the odd bright spot—the communications sector fared reasonably well in 2007, 2008 and 2009, bringing in an average of about 50% of FDI, according to the US State Department.

The African services and consumption uptick is real. Investors, the State Department insists, are showing interest in the central African telecoms, hydro electricity, basic infrastructure and health services sectors. CAR would benefit from such growth, but it won’t happen while the country is divided between Muslim and Christian, or locked in an interminable civil conflict.