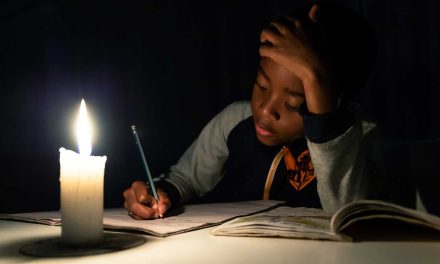

I first encountered Tisa Mothae in 2006 in a bustling part of Bree Street, Johannesburg, where homeless squatters and informal street traders had taken refuge. He started a small, informal clothing business after losing his job in a clothing factory in the aftermath of the 1998 Asian market crash, subcontracting to his former employer below factory gate prices. Then, in 2012, he and others were evicted from the building they occupied and relocated by city authorities to a shadeless part of Alexandra (a Johannesburg township that abuts the affluent suburb of Sandton) that is barren in the dry season and muddy in the wet.

When I met Mothae for the second time on a wintry morning in early 2022, he seemed to invoke the hidden hand of the market in underwriting an urban integration policy strategy that has disincorporated a growing number of black township residents from the state and official economy, shunting them to populous informal settlements. “We were blamed for everything,” he told me. “We brought crime and disease and squatters and foreigners. To add insult to injury, we were barred from trading as unregistered small businesses.”

Despite claims by one Johannesburg policy official I interviewed that “the city faces an explosion of informal settlements and has no choice but to remove them”, attempts at recasting the terrain and managing the crisis reveal an Integrated Development Plan (IDP) starkly at odds with the socio-spatial imperatives of integrated local state formation and inclusive development.

ABOVE: A man reacts as he walks past a body covered by a thermal blanket outside a dilapidated squatter building that caught fire in the central business district of Johannesburg in July 2017. Seven people were killed and another seven injured in the incident. (Photo: Marco Longari / AFP)

There is certainly a strong body of evidence to suggest that whereas township economies on the margins of the city are declining, deregulated markets are pushing up land and property values in well-heeled suburbs and industrial areas, creating new barriers to social inclusion. According to a 2008 IDP spatial development survey, employment opportunities in well-off areas north of the city outweighed residents by a ratio of 22,000 jobs to 14,000 residents. The ratio was inverted in black townships south of the city.

Insights such as these not only illuminate how the trajectory of urban integration has come to define the social and spatial contours now shaping local state formation; they also show how multi-layered limits and constraints of integrated governance, as well as ongoing market logics through which such limits are disciplined and reinforced, have forged a new social dispossession.

In grounding these insights in a theorisation of the link between integrated local governance and the rise of informal settlements, I want to insist on the salience of ongoing processes of dispossession since 1994 to grasp what appears to be an evolving post-apartheid social and spatial narrative: the migration of the most vulnerable out of townships to places where the prospects of finding a house may be slim but squatting is cheap and the proximity to prospective casual employment is convenient.

Such diagnoses underscore an emerging dynamic of South Africa’s post-apartheid growth trajectory, where a burgeoning class of what the Algerian pan-Africanist Franz Fanon, in his withering indictment of ghettoised poverty in post-colonial African cities, described as “non-citizen citizens” who nominally live in cities as political subjects but ambivalently belong in them as social citizens. Indeed, with the homeless now crowding the slums of the city, the government has effectively criminalised more than three million people in the informal economy.

In the government’s attempt to grapple with the problem, dominant policy discourses since 1994 on “integrated governance” and, more recently, “social inclusion”, have framed the problem in terms of an unresolved “national question”. The most widely held policy perspective holds that the proliferation of squatter settlements flows directly from inherited structural legacies of apartheid social engineering in black townships. Thus, a central theme in the race-class discourse on inclusive development beyond apartheid derives from conceptions of black townships as dormitory enclosures during apartheid, which posits that at least until the late apartheid era between the mid-1970s and early 1990s, capital harnessed reserve armies of cheap black labour to its accumulation strategy.

However, whereas the apartheid legacy may define the broad terrain of the post-apartheid transition, it is an inadequate explanation of the problem. Instead, I want to suggest that the dominant policy discourse, highlighting integrated governance as a policy priority, has done more to ghettoise and mask the social costs of capital accumulation behind informal enclosures of resource scarcity, surplus labour and ecological ruin.

From the perspective of current policy concerns about escalating urban poverty, sharply divergent post-apartheid trajectories of local state formation and class formation in informal settlements mark important continuities with apartheid, but they also signify radical departures: they bring into focus how the social faultlines of post-apartheid urbanisation run far deeper than historically racialised geographies.

My central argument is that in the government’s attempt to decompress and corral historical race and class differences into a narrative of “integrated governance” and “social inclusion”, a new class of the poor, disincorporated from the official economy and apparatuses of the state, is emerging as a collateral cost.

In extending this argument to processes of inclusive government, local state formation and sustainable development in South African cities generally, I contend that the freedom to make and remake our cities appears as one of the most existentially barren, legally porous and politically spurious of human rights since the end of apartheid, mirroring the French sociologist Henri Lefebvre’s prescient observation in the 1960s that “the clear distinction which once existed between the urban and the rural is gradually fading into a set of porous spaces of uneven geographical development under the hegemonic command of capital and the state”.

Drawing on Lefebvre’s observation as the primary lens through which I try to convey more concrete insights and meanings on the post-apartheid dynamics of urbanisation, I want to suggest that the government’s macroeconomic framework has had the effect of articulating a false abstraction of social justice.

Complementing this theoretical framework with empirical evidence from burgeoning slums in Johannesburg, we come to see how the spatial configuration of informal communities is shaping a new social dispossession in the post-apartheid transition.

A case in point is a buffer strip of industrial land on London Road in Alexandra. In this indifferent setting an informal slum settlement covering roughly a square kilometre emerges as a liminal zone of a regulatory vacuum. At dawn, tiny tin shacks (colloquially called imikhukhu) appear to “invade” the physical landscape as far as the eye can see before disappearing on the horizon. Its inhabitants refer to the place by a name that comes straight out of the Old Testament. They call it Gomorrah.

Although nominally a part of Alexandra, in practice Gomorrah exemplifies quite different trajectories to the township. For many years the area was a red line between the township and the “official” economy. Since the early 1980s, a handful of white-owned businesses, unfettered by law or public scrutiny, began settling there because property values were low and the supply of cheap, casual labour from the township was plentiful.

Then, between March and June 2020, the closure of factories on London Road during the hard COVID-19 lockdown led destitute families to occupy the buildings. In recalling their version of events to me, the factory owners on London Road were quick to provide contrasting narratives of “chaos” and “anarchy”, portraying the occupation as an “invasion” of their businesses and the surrounding industrial and residential suburbs that lay directly in the path of Gomorrah’s expansion.

Yet the term “invasion” by itself is arid and limited; it abstracts from historically and spatially dynamic processes through which urban slums have come to be formed. Urban slums like Gomorrah exemplify a post-apartheid urban landscape emptied of the original meaning of “city”, which in its original sense is “citizenship”; and so, literally, “the body of citizens, the community”.

In its place, we encounter rising informal ghetto economies in South Africa as spaces where the social costs of growth are decanted into a zone of extra-legality and illegality – an invisible, yet indivisible, boundary where, in Tayyab Mahmud’s poignant portrayal of life in India’s slums, the official economy “finds its spatial limits”.

And so, despite government policy declarations about “revitalising” and “humanising” township economies, we see people stepping outside the law because they are not allowed inside. What appears to be emerging from informal squatter settlements like Gomorrah, then, serves not only as an important caveat of the social and spatial embeddedness of dispossession in post-apartheid South African urban transitions, but also as an emerging paradox: the articulation by the government of slum-dwellers as political subjects while othering them as non-citizen citizens.

To put this in historical perspective, journalist and researcher Hein Marais has depicted the South African transition as an ideological “reordering” of society, arguing that a new dispossession was unleashed by “a masonry of reforms from above since 1996, grounded in a new social compact which set the limits of the possible”. In its formative stage, those limits marked the spatial and social contours of capital expansion in black townships through casualisation and outsourcing that were subsequently remapped onto new geographies of dispossession.

The first phase of economic adjustments under the South African government’s Growth, Employment and Redistribution strategy (GEAR), which Alan Hirsch bookmarks between 1996 and early 1999, witnessed “a retreat of the state from its social provisioning and regulatory duties in favour of the ‘invisible hand’ of the market”. In Hirsch’s telling, GEAR enabled South Africa’s largest corporations to restructure, consolidate and globalise their operations “as a momentary tonic of adjustment”. From this macro level, state power was devolved, through the late 1990s and early 2000s, to sub-national scales of governance on a groundswell of local institutional realignments, economic restructuring, and accelerated capital flows.

The ideological impulses driving this process were starkly evident in Johannesburg where the iGoli 2000 programme became the designated roadmap for a “world-class city”. More concretely, the restructuring of local government unleashed an assortment of social and political tensions around a massive remapping of boundaries through which areas previously designated as “white” and “black” under the Group Areas Act became institutionally incorporated into single administrative entities. The subsequent introduction of the city’s annual Integrated Development Plans (IDPs) in 2003 proposed to radically transform the city’s racially skewed economy, merge financial revenues drawn from municipal taxes, and achieve greater equity between wealthy localities and township economies.

The second phase of urban reordering coincided with President Thabo Mbeki’s “class corporate” agenda since 1999, a conceptual distinction Marais drew as “a series of purely class solidarities, led by the state and a fraction of capital” that eventually form the material and ideological basis for the hegemony of capital. In his attempt to recast the terrain and neuter social instability and political rupture in townships, Mbeki embroidered inclusive gestures to patriotic values with earlier popular entreaties to a “patriotic” black elite. Key to these feats, as Marais argues, “was his deployment of policies geared to service the needs of corporate capital”, along with an emergent stratum of new junior black capitalists and mid-scale entrepreneurs, into a narrative of progress and broad cross-class ideological alliances as a “hegemonic work-in-progress”.

Yet this reordering of society, as political economist Gillian Hart has written more generally of early local economic adjustments, “meant that local governments were assigned the task of not only attracting capital, but also securing the conditions for capital accumulation” – including privatisation and flexible labour – in the face of global competition.

Squatters ready to leave their homes following a Tshwane High Court decision to evict them from government and privately owned land, in July 2001. (Photo: Yoav Lemmer / AFP)

For short periods since 1999, official policy narratives – couched in the official jargon of inclusive local government – veered between stern nostrums of “efficiency” and “fiscal discipline” on one hand, and invocations of local participation, democracy and social justice on the other. “The entrenched dominance of capital in the local economy,” Marais argues, “helped fuel the turbocharged surge of the financial sector, wedged open the economy for speculative international capital and unleashed a wave of cost-cutting, outsourcing and casualisation of labour”.

What is potentially enabling about this sort of analytical framing is that it allows us to move beyond simple understandings of inclusive governance as an emancipatory endeavour. Instead, the focus shifts to inclusive governance and social justice as a disciplinary duty. Within this milieu, the performance of disciplinary duty falls, as Marais argues, on “shoehorning the assortment of social tensions into a false narrative of social justice broadly centred on social provisioning”.

And therein lies the rub. As the perceptions of business owners on London Road attest, the issue is quite convenient to those who control the economy, for it reminds the government of its policy priorities. Indeed, one of the government’s celebrated policy declarations has been its acclamation of growth as a basis for social inclusion. However, in the passage from apartheid to post-apartheid cities, government policymakers may display a studied courtesy to the poor, invoking palliative concepts such as “inclusive governance” and “social justice”, but the underside of growth is social exclusion.

One of the most abiding myths to emerge in official policy discourse has been the failure of the official economy to grow at rates that benefit the poor. Yet, as a growing literature on “degrowth” economics demonstrates, the fate of the formal and informal economies has remained entangled, with cruel disappointment for the latter born of the prosperity of the former. If the Johannesburg city official I spoke to is right in worrying that “it is in the city that the greatest pressure for reform lies”, then Henri Lefebvre was right to insist that the solution must be economic – just not along the current growth trajectory.

Malcolm Ray is a research consultant and author of two scholarly books, titled Free Fall: Why South African Universities are in a Race against Time and The Tyranny of Growth: Why Capitalism has Triumphed in the West and Failed in Africa. Malcolm’s subject speciality is economic history. His writing deals directly with themes of power hierarchies, race and gender discrimination, and class inequality. His current work focuses on the shifting dynamics of urban livelihoods, economic growth and power relations that allow for the development of theorisations of the economy and polity more relevant to post-colonial contexts. Malcolm began his career as an anti-apartheid activist during the 1980s and early 90s. He practised journalism for more than a decade before becoming a financial magazine editor in the early 2000s. He was a Senior Fellow in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg and editor of four premier South African and pan-African business and finance magazines.