The topic of ethnicity rears its head all too frequently, not just in Africa but globally, as we confront identity politics and notions of sameness and difference. Consider the contentious, contemporary spread of Syrian refugees seeking asylum and the Trumpomania surrounding Mexicans entering the US.

Much as ethnicity can be a clarion call for solidarity, it can be divisive and fatal. I recall an anti-xenophobia project in Durban with Congolese refugees and Zulu street traders a few years ago. An elderly, dignified Congolese pastor shared his most degrading experience. While queuing diligently at a taxi rank, he was spoken to in isiZulu by a local youth. When he could not reply, he was told, “you are a monkey” and barked at to move to the back of the line, which he promptly did.

Despite his having witnessed many war-related atrocities in the DRC, when the pastor returned home he looked at himself in the mirror, while remonstrating with the divine, “but I am a human person, not a monkey”. The vitriol is only a hop and a skip away from mass genocide, reducing a human to a mammal, then a “cockroach”, with the resultant extermination that witnessed the slaughter of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus in 100 days. Racism knows no colour and the ethnic barriers of racial absurdity don’t discriminate when opportunities to incite violence present themselves.

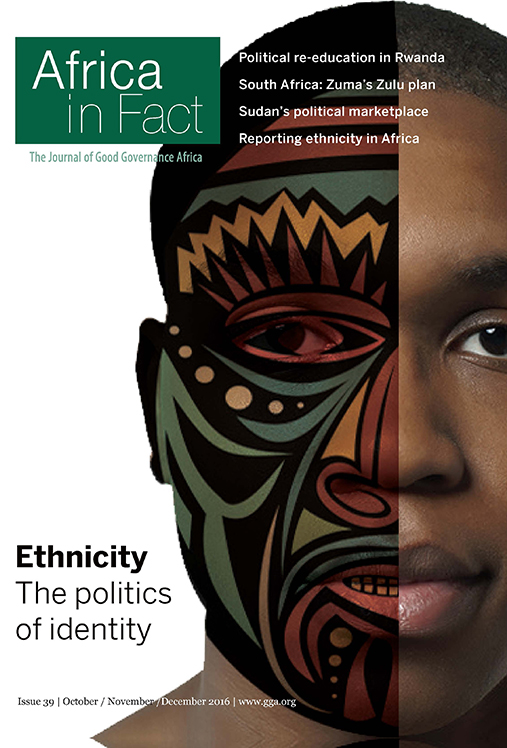

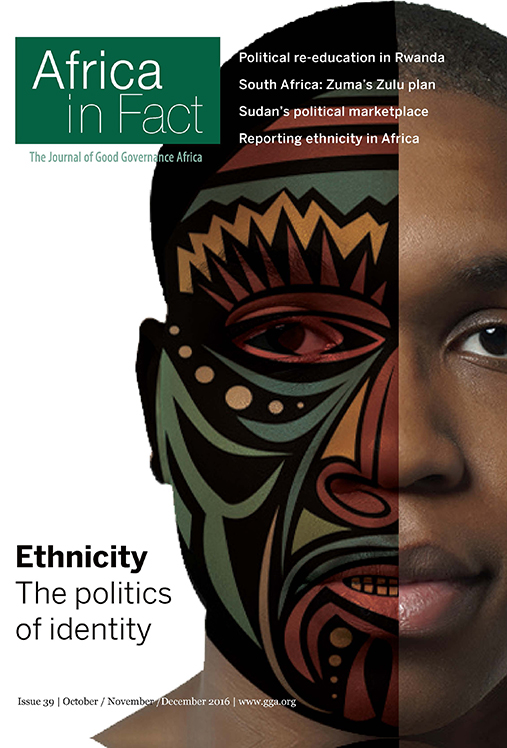

Thus it is that our current issue of Africa in Fact tackles ethnicity and related challenges head on, with hard-hitting articles from across the continent. As Michael Schmidt points out, ethnicity is a dynamic and multidimensional concept, making it tricky to use at the best of times, as he identifies with respect to outbreaks of communal violence where ethnic differences exist.

We engage the messy reality of post-conflict “nation-building” and concomitant suppression of ethnic identity, as witnessed in Rwanda. We look at how ethnic privilege and power politics fit hand in glove. It isn’t necessarily always the largest ethnic group that holds sway; at times minorities can pack the punch, as our authors show. Think Kenya, Namibia or Nigeria versus Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Morocco and Uganda for examples.

The question of ethnic inclusion or exclusion remains significant; at the inter-tribal level, consider the conflict between the Dinka and the Nuer in South Sud

an; at the tribal level, observe the Zulu-fication (Zuma-fication?) of the ANC in South Africa; and at the clan level, regard the intra-Zanu-PF contestation in Zimbabwe. In the case of Somalia, ethnic marginalisation and the resultant desire for economic and political gain, rather than religious zeal, fuels recruitment to Al-Shabaab.

Africa may have been carved up according to fabricated and arbitrary boundaries by 19th century European powers, but Milton Allimadi shows just how entrenched the legacy of Western literature’s conceptualisation of Africa remains in the 21st century. The consistently inappropriate, tribal mumbo- jumbo often found in Western writing about the continent fails to reflect the complex nuances within which the colourful kaleidoscope of African peoples and our rich cultural prisms operate. Conrad’s “Mistah Kurtz – he dead” died a long time ago. So-called pidgins and creoles are evolving into expressive and powerful new languages, as Sierra Leonean Kriol shows.

Amidst the vast ethnic diversity across Africa, we return to what it is that unites, and that is human personhood. It remains all too easy, and often politically convenient, to maintain fault lines along difference, and in particular ethnic (and increasingly, religious) difference. I was horrified that in a book published by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, entitled “100 days: in the Land of a Thousand Hills”, Hutus were portrayed with red eyes, demonic frowns, deranged and primal, while Tutsis were portrayed as Westernised, refined and serene.

The reality is much more complex than this.

Stereotypes are unhelpful, as is the suppression of dialogue around very real issues of ethnic similarity and difference within the nation-state. The polarised portrayal of ethnicity as X good or Y bad is most often constructed around a disturbing ideological agenda, far from the truth that all ethnicities contain the potential for harm or for good. There should be no first, second or third class citizens, just human persons. Any other approach promotes ethnic apartheid and a dangerous dehumanisation, with disastrous and often deadly effects.

Alain Tschudin

Executive Director

ALAIN TSCHUDIN is a former Executive Director of Good Governance Africa. He is a registered psychologist with Ph.D.s in Psychology and in Ethics. He was a Swiss Academy Post-doctoral Fellow at Cambridge and oversaw the Conflict Transformation & Peace Studies Programme at UKZN for several years. He has broad research and community engagement interests and has worked for various universities in Africa and Europe, with the European Commission, with local and international NGOs, as CEO of a leadership development agency, and as lead consultant for Save the Children and UNICEF, most recently as Child Protection Assessment Coordinator for Northern Syria. Alain has an adjunct association with the International Centre of Non-violence (ICON) and the Peacebuilding Programme at the Durban University of Technology.