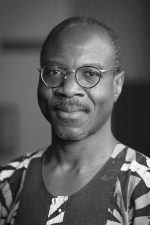

World renowned photographer Malick Sidibé outside his studio, Bamako, Mali Photo: Graeme Williams

Contrary to popular belief, Africa’s fortunes and modernity have been intertwined for at least two and a half centuries

Africa’s challenge to modernity – and the continent is by no means alone in this – should be understood in terms of the following: (1) what have been the relations between Africa and modernity? (2) how has Africa and its phenomena featured in the discourse of modernity? and (3) why should we care about these questions?

Modernity refers to that movement of ideas, practices and institutions that originated in Europe and filled out with accretions from across the globe. This means that we should not conflate modernity with westernisation. Modernity’s philosophical discourse interests us because, ultimately, its most lasting impact has been the creation and wide dissemination of a new and radically different view of human nature unique to it, as well as pertinent values, practices and institutions that have promoted the efflorescence of this philosophical anthropology.

We identify three core tenets: individualism, the centrality of reason, and the idea of progress. The notion of the individual that is dominant in the modern age is without precedent, at least in the Euro-American tradition from which the remaining parts of the world that have embraced modernity extracted it. Under modernity, individualism is the preferred principle of social ordering and almost everything else is understood in terms of how well or ill it serves the individual. In the modern epoch, the individual is not merely supreme; whatever detracts from the rights of the individual is, precisely for that reason, to be rejected. Individualism underpins the most dramatic innovation introduced by modernity: the principle of governance by consent. Under this principle, no one ought to acknowledge the authority of, or owe an obligation to obey, any government to which the governed have not consented.

The second core tenet is the centrality of reason. The modern age is where knowledge is founded, not on revelation, tradition or authority, but on conformity with reason. Here, the claims of tradition and authority do not mean much, and every truth claim must be authenticated by reason. Whoever can show that she has superior knowledge commands our assent and respect.

Modernity is a horizon of time. It is a horizon that is always open to the future; one in which things never are, they are always becoming. This yields a near obsession with the “new”. Change is celebrated for its own sake, an orientation marked by an abiding faith and singular commitment to progress. The belief in the desirability and possibility of progress underpins the restlessness of the modern age in which nothing is regarded as settled and the best always is yet to come.

We may now respond to the first of our three questions: what have been the relations between Africa and modernity? Rocky, to put it mildly. This is partly traced to our misapprehension of the timeline of modernity in our continent, especially in West Africa, when we ascribe its induction into our continent via colonialism. We are often led, erroneously, to dismiss modernity as part of the colonial legacy. However, I would argue that modernity being on offer in colonial Africa would have made for a better life and more salubrious history than what colonialism actually bequeathed to its victims. Given the quantum leap forward that modernity represented in humanity’s evolution towards ever more humane ways of living and being human, I believe a modern Africa would be a better place to be than Africa now.

To take modernity seriously we need a different genealogy of it in Africa. Historically, specifically in West Africa, Christianity was the vector for the introduction of modernity. Contrary to accepted wisdom, colonialism aborted the transition to Christian-inspired modernity that was afoot, under native agency, before formal colonialism. This means that when we think of the history of the relations between Africa and modernity, we should do so in terms of the Africa-modernity relation before colonialism and the same relation after colonialism. Our attitude towards the Africa-modernity relation is conditioned by whether we accept this timeline. If we do, some of the conundrums associated with the relation will begin to make sense.

First, the near total absence of African intellectuals’ contributions to the discourse of modernity will astound even more profoundly once it becomes clearer how the absence was constituted and why it persists. It will also clarify why it seems that the only relationship that African intellectuals now can or do have with modernity is one of conflict rather than embrace. Finally, it will enable us to retrieve more aggressively those works by Africans of the period before colonialism who had made modernity their own and sought to remake their communities in its image.

Africa’s challenge to modernity, in part, requires African and non-African scholars of modernity to explore in more depth the works of Africans who, under the tutelage of Christian missions, had been inducted into modernity and had become apostles of the way of life it enjoined. Among them were Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first African-Anglican bishop and a polymath, James Africanus Beale Horton, a surgeon, scientist, soldier and philosopher, and Samuel Richard Brew Ahoh-Ahuma, a journalist, writer and politician. They were frustrated in their efforts once colonialism was imposed and, unfortunately, our current understanding of the relations between Africa and modernity has been framed by this colonial inflection.

The latter cohort of administrators and missionaries, and from the third quarter of the 19th century onwards, denied the humanity of Africans and deemed their societies backward. Gradually, modernity in the African imaginary became one with that in the name of which Africans were imperialised and brutalised. Racism-dominated colonial education ultimately extirpated the memory of the earlier African converts to modernity. That very few Nigerians know more about Samuel Ajayi Crowther than that he was “the slave boy who became a bishop” is the ultimate testament to how completely colonial miseducation structured the collective memory of educated Nigerians. Post-independence African scholars are yet to remove this mind block that dissuades them from embracing modernity as a matter of principle, rather than as a matter of expediency. That attitude permeates the continent.

Many of us Africans are afraid of autonomy, the very core of individualism. It is a double-edged sword. When one messes things up, she must take responsibility for her actions. Are Africans so ready? I always marvel at the ability of African leaders to bask in the role of the appointed beggars to the world. They never dream big dreams. They take no big risks. They are always satisfied with the handouts from their erstwhile imperial rulers, forever begging for increases in their pocket money, welfare amounts, call it what you will. Either they have forgotten or, worse still, they never learned how to be subjects and cannot be bothered to acquire the sense of being one. I am glad to report that Ethiopia seems to be bucking this trend.

In lieu of autonomy and the risks that it entails, we have persistently embraced the aid model fashioned by colonialism, which denied our basic humanity. It put us on aid, atrophying our subjectivity and weakening us enough that we hardly ever think of solving our problems ourselves without reference to Europe, America and, now, Asia. Our will is bent by our donors; we require their approval for the minutest changes in direction in running the affairs of our so-called sovereign countries. It is a mark of how inured to aid the continent has become that we do not see Africans, especially their intellectuals, thundering against the indignity that comes with our being the appointed mendicants to an increasingly affluent world. Africa’s leaders dutifully troop out to wherever anyone promises us alms.

This brings me to the second of our questions above. I will be brief here. How have Africa and its phenomena featured in the discourse of modernity? Looking at the narratives of modernity’s discourse, Africans seem to have only ever been victims of modernity – not theorists of it or contributors to its construction. Nothing could be further from the truth. But the reason for the absence is easy to fathom. Given that by the time of independence in various African countries, the mode of education had become completely dominated by the tropes of colonialist pedagogy and historiography, African intellectuals trained under that regime were, for the most part, amnesiac towards their own heritage or thought lightly of it. Those who thought highly of it paid a stiff price in denials of opportunities for advancement, especially in African institutions. African graduates continue to have the most perfunctory understanding of the contributions of our own intellectuals, past or present.

We should acquaint ourselves with the heritage of intellectual ideas in the global African world, regardless of the judgment of Euro-American institutions and scholars. If you write, read, and discuss it among yourselves, they will read and discuss it, following your lead.

Many countries in Africa are instances of what are called newly democratising countries, trying to install modernity-inflected liberal representative democracy. But the debates taking place in the continent hardly reflect any serious engagement with the philosophical template on which this democracy is based. We hardly ever have debates about the freedom of the individual, about the rule of law, about taxation and representation, about the responsibility of the governors to the governed, or the basis of governance in the consent of the governed. All of these are supremely modern principles that, curiously, no longer feature in the political discourse in our lands. This has not always been the case.

In the immediate post-independence period, multiple parties contended for votes, before the scourge of single-party rule and the cancer of military rule combined to arrest the continent’s development in all directions. Parties – and their leaders, in many cases – fought elections and canvassed their respective electorates on the basis of ideological divisions based on philosophical orientations regarding human nature, the nature of society, the appropriate relation between the individual and the state, the grounds of legitimate power in the polity and the privileges and forbearances of citizenship.

Current African political leaders and intellectuals either believe that the philosophical template is already realised in contemporary African polities or do not think that such themes are relevant to their thought and practise of democracy. What is clear is that African politics has become reduced to “ethnic balancing”, “religious permutations”, “feeding the people”, and other such inanities. For the most part these days, political parties in African countries exist to win elections so that they can become the sole distributors of largesse. There is hardly any debate about the core questions of political philosophy, and the parties are nondescript patchworks of personal and regional interests dominated by moneybags and their sycophantic hangers-on.

The rich legacy of freedom and self-determination bequeathed by earlier thinkers has been dumped for an obsession with just keeping life going! African politicians and intellectuals must re-engage the issues of freedom and self-determination, of building knowledge societies dominated by reason and an abiding faith in our capacity to build a better and more humane world for all within our borders.

To the extent that we reintroduce the attainment of these ideals as a metric by which to judge the quality of our polities and the performance of our politicians, to that extent would we be restoring to the centre of our concerns the dignity of even the lowliest Africans and their capacity to lead lives marked by self-control and beauty. Hence, to the question of why we should re-engage with modernity in the contemporary world the answer is simple: doing so promises a better life for Africans than what is on offer at present.

In conclusion, in talking of the challenge of Africa to modernity, the most important issue is not to talk as if Africa is squatting outside of modernity and is to be understood as asking modernity to show why she should do business with it. Africa’s fortunes and modernity have been intertwined for at least two and a half centuries. We must fight those who seek to keep Africa apart from the rest of humanity and under some or other system of patronage, while at the same time forcing the world to see what the African world has made of modernity in her own idioms and invite the world to drink from its wisdom, of which there is abundance. A culture of hope must supplant the current philosophy of limits.

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò is a teacher, thinker and humanist, working out of the Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University in the US. His research interests include philosophy of law, social and political philosophy, Marxism, and African and Africana philosophy. His writings have been translated into French, Italian, German, and Portuguese. He has taught at universities in Canada, Nigeria, Germany, South Korea, and Jamaica.